Carry That Weight: The Revival of Feminist Performance Art

by Stassa Edwards

Mattress Performance: Carry That Weight began nearly five weeks ago. Throughout the performance the artist Emma Sulkowicz, a 22 year-old Columbia University senior, will carry a boxy blue mattress everywhere she goes on campus. Weighing in at fifty pounds, the mattress stands in for the mattress on which she was raped by a fellow student. Sulkowicz’s work is profoundly simple: a young woman visually manifests the psychological weight of the crime committed on her body and demands recognition of that burden. Carry That Weight is a purely visual performance, one so piercing it resists language.

Like most performance art, Sulkowicz’s piece has clearly defined parameters, what she terms “rules of engagement.” They are: the performance will last until her rapist has left campus. The mattress will only be carried on campus. She cannot ask for help, but can accept it once it is offered. Once a person helps her carry the mattress, they enter into “the space of performance.” By quite literally bringing the site of the crime (in this case an ostensibly “safe” domestic space) into public sight, Sulkowicz’s performance relocates its subject in between the shifting grounds of public and private, personal and political.

Carry That Weight implies that within the discourse surrounding rape, the separation of these categories are meaningless. The public and private cannot be separated. The discourse of rape inhabits the public, private, personal, and political simultaneously. Carry That Weight’s poignant acknowledgment makes Sulkowicz’s performance one of the most salient pieces of feminist performance art produced in recent memory.

Carry That Weight has a revival quality, renewing a 1960s tone of radical consciousness-raising: defiantly political, resistant to silence, and deconstructive of cultural definitions of rape. And since Sulkowicz’s performance has easily been one of the most discussed artworks of the year, I want to revisit some of the women who have tread in ugly discourse of rape culture; to return to a long artistic project that, like Sulkowicz, sought to dissect aspects of that culture and expose vernaculars of terror.

I could write an entire history of art on the bodies of rape victims. Leda, Susanna, the Sabine women, the daughters of Leucippus, Io, Dinah, Europa, Lucretia, and Daphne are just a few of the real and mythological women whose rapes appear as famous works of art. The list would go on and on.

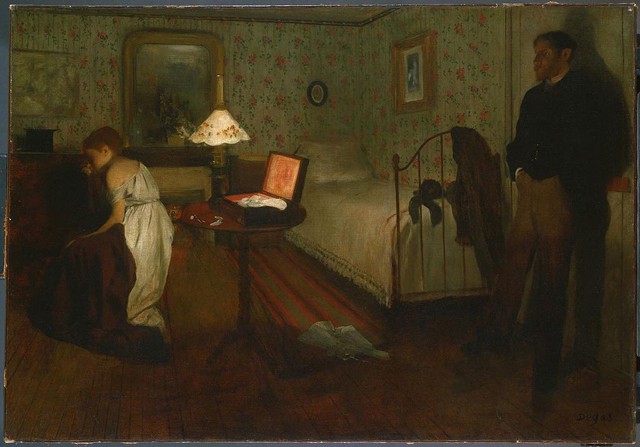

In the history of art, rape scenes, lusciously painted and beautifully sculpted by the so-called Old Masters, are often called “heroic rapes.” Heroic because the narrative is one of tension: a struggle, followed by rape, and then total capitulation to romantic love. Heroic because the Old Masters could capture that tension and render it in paint — think of the dimpled, nude women of Peter Paul Rubens’s The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus, their writhing forms bringing compositional order to a chaotic scene. Heroic because some of these women killed themselves to protect the ambiguous moral concept of honor. Heroic because assailants are the gallant founders of Rome or residents of Olympus. Heroic because the erotics of violence could mask itself beneath an aesthetic reflection on mythologies.

In this history, heroic rape is uncomplicated: victims are willing, rape is pleasurable, romance inevitable. Heroic rape still haunts the history of art. There is a tactic acknowledgment that artistic expression is written on the bodies of women, that the violence of the gaze is inevitable. But there is another kind of rape scene too; artistic narratives that are perhaps less heroic, less celebratory of the power of ancient men, far more unsettling in their radical approach. Images that expose the aggressiveness of merely looking.

In the late 1960s, feminist performance artists began to intervene in the heroic rape scenes of the Old Masters. They questioned the celebratory depiction of violence wrought on the bodies of women, and also isolated an enduring narrative that, in hushed tones, had effectively echoed the myth of heroic rape for centuries. Yoko Ono, Ana Mendieta, Suzanne Lacy, Nancy Spero, Jenny Holzer and Tracey Emin scrawled over the erotica of violence, replacing the shapely, acquiescent bodies of Rubens with the voices and bodies of abused women.

Throughout the 1970s, the radical consciousness-raising of feminist art, particularly performance art, looked like it would succeed in its political and artistic aims. There was a proliferation of feminist art, with collectives like WAR (Women Artists in the Revolution) being formed, journals published, institutions established to exhibit the works. But the radical moment was short-lived: the confrontational aims of radical, feminist art had always been resistant to the profit mode of the art gallery (who wants “real” rape hanging in their home?).

But it’s worth reviving again because, like Sulkowicz’s work, so much of feminist art grapples with violence, culture and art. And in the midst of fractious political debates about “legitimate” rape, campus rape, and “forcible” rape — the deconstructive work of feminist artists is mournfully relevant again.

The history of feminist art is a history of the body; of the ways a woman’s body can be terrorized, how that violence is internalized, and the subsequent expression of that violence. The bold expression of fear underpins the rape narratives of feminist art.

Yoko Ono’s 1968 film Rape, a 77-minute documentary, captures the easy terrorization of women in public places. Rape follows an unsuspecting and unnamed twenty-something woman, pursuing her through the streets of London.

The woman, Eva Majlath was, at the time, illegally living in Britain and spoke little English. Ono was not present for the film. She hired a male cameraman to purse Majlath, who was unaware she was part of the work.

Rape is a difficult film to watch. Majlath’s increasingly panicked responses to a strange man approaching her in public are familiar. At first she smiles, uncomfortably trying to assuage and perhaps assess the intentions of the cameraman. The language barrier makes communication impossible. She becomes increasingly panicked and tries to run away, even running into traffic to avoid him, before succumbing to the overwhelming reality of fear. Sobbing, Majlath crumples into a corner of her apartment.

Rape is challenging on a number of levels, such as the deeply troubling ethics of the film itself: Ono arranged for a woman to be relentlessly pursued without her consent.

Ono has maintained that her collusion poses questions about women’s “complicity when working within patriarchal image-making.”

Ono’s answers are hardly satisfying, but they acknowledge the proximity the film’s viewer has to both artist and exploitation. Watching the film makes the viewer a proxy for both artist and cameraman, part of and complicit with the act of terror. With no narration to frame response, the viewer too, partakes in the thrill of the chase.

Indeed, the excitement of watching terrorized women — their harassment in public places and its seepage into domestic spaces — is an old filmic trope, particularly in thrillers. As one critic of the film later noted: “Ono knew it would be safe (camera equipment is expensive) to terrorize someone on the street only if that someone was female.”

What striking words — the safety of terrorizing women.

While a student at the University of Iowa, Ana Mendieta performed Untitled (Rape Scene). Mendieta conceived of the performance in response to the brutal rape and murder of a fellow student, Sara Ann Otten, in 1973. Mendieta invited her classmates to her tiny apartment where, through an open door, they found the artist stripped from the waist down and bent over a table. Blood smeared over her naked body, dripping down her legs and pooling on the dark floor. Broken bric-á-brac and bloodied clothes were strewn across the floor. Later, Mendieta described the scene: “[the audience] started talking about it. I didn’t move. I stayed in position about an hour. It really jolted them.”

Mendieta continued iterations of Untitled (Rape Scene) throughout the year, challenging fellow students to confront the bloody violence of rape. In Rape Performance she again posed naked and bloody, but this time outside on campus, her body draped over a log. In Bloody Mattress (1973), she staged a crime scene, abandoning a blood-splattered mattress at an abandoned farmhouse on campus and waited for it to be discovered. None of these works were reenactments. Rather, they were drawn from the media’s framing of rape (particularly Otten’s) and “a reaction against the idea of violence against women,” Mendieta later said.

In 1980, she commented that the rape had ‘moved and frightened’ her, elaborating: “I think all my work has been like that — a personal response to a situation … I can’t see being theoretical about an issue like that.”

In 1977, as a response to the cultural conditions that had allowed Ono’s and Mendieta’s work to be produced, Suzanne Lacy staged Three Weeks in May. The three-week performance took place at multiple events throughout Los Angeles, mapping the sites of rape throughout the city. Lacy graffiti-tagged sidewalks, “2 WOMEN WERE RAPED HERE, MAY 9, MAY 21.” She drew a large, yellow map of the city, publicly displayed it downtown, each morning stenciling “RAPE” in bold, red font on the map to name the sexual assaults that had been reported to the LAPD the prior day.

“What this map is about, what the whole project is about, is women speaking out to each other,” Lacy said, “sharing the reality of their experience. By exposing the facts of our rapes, the number of them, the events surrounding them, and the men who commit them, we begin to break down the myths that support rape culture.”

Carry That Weight has shades of Lacy’s performance: collaborative and public, it graphs the violence of rape to a site-specific location. They both examine the issue of cartography, the maps — both physical and internal — that rape culture continually draws. Lacy demarcates scenes of crimes, labels the public spaces most dangerous to women, while Sulkowicz’s mattress reminds that the cartography of danger expands beyond urban streets and into comfortable, domestic spaces.

In all of these works, safety is merely perception; fear is very real.

These works all traverse the terrain of the fear and violence that map women’s lives. They acknowledge that violence and fear determine women’s geography; that women are constantly being located and relocated within that prescribed space, that our movements are regulated by that geography (don’t go here or here or here, don’t seek out danger). But that mapping operates two-fold. It is given to us and subsequently internalized, as Nancy Spero once said: “All women carry this inherent knowledge, that we can be raped, that we are in danger.”

Sulkowicz, like Mendieta, made me think that the artistic intersection of the personal with political is the most profound way to challenge rape culture. I think too of Patricia Lockwood’s Rape Joke, an absurdist gesture that questioned both the stereotypical language it employed and the structure of poetry:

“The rape joke is that this is finally artless. The rape joke is that you do not write artlessly.”

Lockwood’s poem recalls Lacy’s 1976 book Rape Is…, a pseudo-dictionary of rape culture’s infinitely shifting meanings: “Rape Is…” reads one passage, “when your boyfriend hears your best friend was raped and he asks, “What was she wearing?”

We should acknowledge the violence outside the frame of these works. We should acknowledge that while Ono and Mendieta’s works were “fictional,” that violence operated in and around the lives of these women.

Eva Majlath was murdered in 2008, beaten to death in a domestic dispute. Her body was dismembered and set on fire. It took the police months to find her remains, buried a few feet from her home.

Mendieta, “somehow went out the window” falling 33 stories to her death after a loud argument with her husband.

The violence that spurred Sulkowicz’s project was not “fictional;” it was real and her rapist still walks the same campus grounds where she is currently performing.

That seems to be the reality of violence: it can never be kept at bay or limited to the realms of the artistic or the political. It will always inevitably manifest itself in the lives of women.

When I look at Sulkowicz’s work, I see shades of Ono, Lacy and Mendieta, but she signifies more than just fear and violence. Carry That Weight also centers a body reconstituted after violation (by both her rapist and a legal system that protects him) and the pain of that reconstitution.

Sulkowicz’s work is powerful because it expresses what cannot be narrated. The visuals are striking, the elucidation of pain is so heart-wrenching; the reference to violence, infuriating.

I want to say that Sulkowicz is brave, but that seems too glib of a word to describe her performance. Carry That Weight fractures language to disperse the routine phrases we use to characterize rape or its survivors.

And indeed, language fails me here. To summarize Sulkowicz’s work is only to arrive at a series of conclusions that are at best fractured: conflicted by mournfulness and anger, infused with a certain kind of numbness developed to armor myself against the familiar repetition of violence. And perhaps that’s why Sulkowicz’s work pierces me, the burden she reenacts chips away at that numbness, recalling a history of art that is striking in its righteousness. Ono’s film is forty-five years old, yet she could still, today, reproduce an identical kind of terror in nearly any woman. I am reminded that personal cartographies are still formed by violence.

Stassa Edwards is a freelance writer and PhD candidate living in the Deep South. For more of her misguided opinions, you can follow her on Twitter.