An Extensive Catalogue Of Bodily Impulses

by KelliKorducki

The summer I was 22, I tagged along with a group of samba percussionists to a music festival at an organic farm in southern Ontario. My ride would be free so long as I assumed the role of “Bus Captain” on the decrepit yellow school bus they’d rented for the occasion.

I was about to enter the fifth year of my undergrad degree — an attempt at postponing Real Life. I’d just returned from a summer of data entry temp work in my Midwestern hometown and was not quite a grown-up but definitely, somehow, a woman. The cubicles that had neighbored mine in the office complex were occupied by lifers of secretarial school vintage. There was the meticulous brunette whose current weight loss scheme involved a plot to contract salmonella from that season’s national outbreak of contaminated tomatoes, and — my favorite — the whip-smart grandmother who’d introduced herself by verifying that I was, in fact, related to the same long-retired Dr. Korducki who had once been her OBGYN. “He delivered all three of my babies!” she kvelled. “Such a good doctor, so old-school and gentle. Even though, between you and me, he had serious sausage fingers.”

In our break room, our conversations all had the frank familiarity of a group with little in common apart from the intermittent hilarities of being women. Half-hearted exchanges on muggy weather found their stride only after talk turned to boob sweat (“If they don’t turn up the AC I’m gonna have the Rio Grande running down my top”) or how much the Pill sucked in the ’70s (“Dried you out so bad, you could start a campfire down there”).

So when, on the yellow bus, a girls’ school biology teacher in her late-twenties explained that her students’ first assignment each year was to take a hand mirror to their buttholes and “really let yourself take it in,” I got where she was coming from.

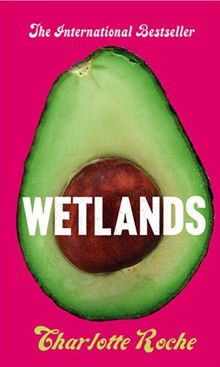

“Unlike other people, I know exactly what my butthole looks like,” says Helen Memel, the 18-year-old protagonist of Wetlands, on the third page of Charlotte Roche’s 2008 novel. Memel knows because she gazes at its reflection every day, cheeks pulled apart, in order to shave it. But she doesn’t love feeling bound to social niceties like asshole depilation, so she half-asses (sorry) the routine, nicks herself, and gets infected. The injury sends her to a hospital bed for several days — European healthcare! — where she mulls over her sex life and her parents’ divorce, the kind of broodings you’d expect from a person bedridden for some time with an abscessed asshole.

The book hones in on Helen’s extensive catalogue of bodily impulses, dropping enough deep thinks on corporeal intervention to give the Hippocratic Oath a run for its money. Pus, menstrual blood, shit and vaginal fluids — it’s all fair game for Helen Memel.

“I use my smegma the way others use their vials of perfume.”

“My fingers are kind of short, so I don’t get too far when I’m looking for something in my pussy.”

“Hygiene’s not a major concern of mine.”

Disgusting, right? I was totally taken. I read honesty in Helen’s pokes, prods, insertions and smears, and began to think about my own tendencies toward the gross. I also think hygiene’s overrated! I kind of enjoy the smell of BO! Pooping is the best! There’s endless intrigue in the parts of ourselves we keep under cover, those humbling holes and smells and secretions that do what they’re going to do whether we like it or not. Wetlands didn’t just unveil these things — it made them fun. Helen’s relationship with her body didn’t come off, to me, like the mark of a disturbed teenager, but like a baby step beyond where we all take ourselves every day. Who hasn’t gotten their kicks popping a zit?

I was hardly alone in falling for Helen Memel and her goo. Wetlands became an instant bestseller; it’s now been translated into 27 languages. The 2013 film adaptation, which gets an ultra-limited US release this week, opens with an onscreen quote from one aggrieved reader to the editor: “This book shouldn’t be adapted to a film.”

At The Guardian, Granta editor-turned-physician Sophie Harrison dismissed the novel’s driving conceit — Helen’s fixation with nearly every potential use and byproduct of her bathroom bits — as a played-out ploy to shock Anglo sensibilities. It’s a fair enough point, if one assumes Roche’s primary aim is to scandalize. I don’t, but more on that later.

Roche is quoted in a 2009 essay from The New York Times’ Sunday Book Review as saying that she wanted to write about the “ugly” and “smelly” parts of the human body. That same review pans the novel for, to paraphrase the Times, lifting old feminist tropes around sexual liberation by way of bodily juices and bludgeoning them to death with a hemorrhoid pillow.

As a feminist critique, it’s true that Wetlands doesn’t tread new (or even new-ish) ground. Helen Memel has no qualms about sampling her own vaginal secretions, but Germaine Greer was recommending that women taste their menstrual fluid nearly a decade before Roche was even born. And despite its squirmy close-ups, the story doesn’t offer a generation raised on Internet porn all that much to blanche over. Wackier shit is out there, and a whole lot of the book’s readers — and film’s viewers — have seen their share.

I don’t think the point of all the gross-outs is to preach or shock but to amuse and, maybe, normalize. Helen’s approach is extreme, but we could all do with a more playful curiosity about our own marshes and swamps. This isn’t a radical observation, but it bears repeating that in a society where women especially are expected to be plucked and polished, revelling in the body’s “natural state” (read: occasional nastiness) is a subversive act. Why not just get into it?

When I read the book, not too long after that summer on the school bus, it didn’t feel dialectic. It felt obvious. I understand why someone would write a coming-of-age novel about the endearing grossness of the human body, which only gets grosser with the passage of time. Our collective grossness is a great uniter — maybe the great uniter. Think of shared indignity as a gift.

On the school bus, I asked the high school biology teacher how her mirror assignment was received at school. Well, she told me, the other teachers don’t love it, but the kids were usually won over. “One girl thanked me,” she said. It was the best assignment she’d ever gotten, the girl had reported, her butthole not unlike a dried-up Cheerio.

Kelli Korducki has written for The New Inquiry, Rookie Mag, Hazlitt, and other places on the Internet and in Canada.