How to Be a Genius (Or, How to Contract Syphilis and Be An Artist)

by Stassa Edwards

It seems that James Joyce was not the simple hypochondriac he’s often assumed to be. Rather, with his panoply of debilitating symptoms, he was something far more romantic: a syphilitic. According to a new biography, if the long-whispered rumors about Joyce’s burden are true, he had the French Curse, the Spanish Itch, the Canton Rash, or whatever delicate nickname he preferred to use.

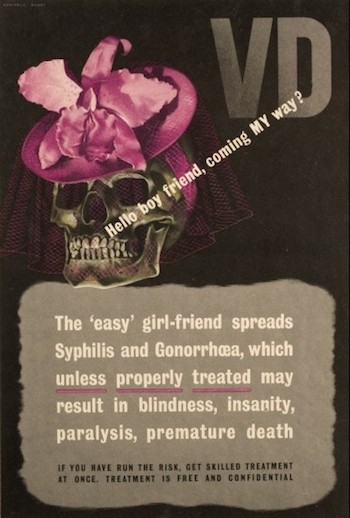

Artistic genius and syphilis are strange but habitual bedfellows. (For men, of course; women with syphilis are just diseased prostitutes.) Joyce was in good, grossly infected company: Charles Baudelaire, Vincent van Gogh, Beethoven, Francisco Goya, Oscar Wilde, Gustave Flaubert, Édouard Manet, Guy de Maupassant, and Friedrich Nietzsche were likewise plagued. It’s rumored that Edgar Allen Poe, Albrecht Dürer, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky suffered the social disease as well. Each exhibited varying symptoms that ranged from paralysis to insanity to poor eyesight, abscesses and boils, loss of hearing, and diminished limb function.

In its final stages, syphilis was as grotesque-looking as it was painful. (WARNING: That link is safe for neither work nor your soul.) But syphilis was also, if not a surefire path to artistic immortality, at least a helpmeet to those who were already on their way. The internet teems with writerly advice, almost all of which suggests that creativity is served best by monasticism, a quiet life filled with pencils — but that kind of advice seems to take a very short view of history, overlooking the one classic way to rouse the capricious Muses: sexually transmitted disease.

After 1459, when the disease traveled from its epicenter in Naples — carried to nearly every European nation by returning soldiers — syphilis and its symptoms became nearly synonymous with men of arts and letters. It displaced other less-romantic diseases; its rise made the tuberculosis of John Keats and the vague maladies of Alexander Pope look downright pedestrian. Not even Lord Byron’s dreamy club foot could compete with the clap.

“Syphilis, of course, brings on madness and suffering and eventual death,” opined Susan Sontag, “but between the beginning and the end, something terrific happens to you. You kind of explode in your head and are capable of genius.” Sontag assured afflicted writers-errant of at least “a decade or two of the most intense and frenetic mental activity before you collapsed into total madness.”

Here’s a handy how-to guide for hearing the muses, taken from the lives of humanity’s most prolific, syphilis-plagued geniuses.

Step 1: Find a prostitute. Like Joyce, artistic geniuses (and perhaps men, in general) always claim women as the source of their contagion. To signify an even more liberated, avant-garde lifestyle, seek out not just any woman of the night but the vintage kind that doesn’t believe in “penicillin.”

Women of ill repute are easily found by patronizing the “bawdy houses” of St. James in Regency London or strolling the Champs-Élysées in nineteenth-century France. The streets of Naples and boarding houses of Rome are also suitable. If you’re still having a difficult time, consult your closest Impressionist painting; many double as reliable guides to locating prostitutes.

All the better if you, like Baudelaire, can find a woman so repulsive that both your friends and history will question your judgment. The poet likely contracted the disease from his partner, a prostitute named Jeanne Duval, though it might have been from one of the other numerous sex workers whose addresses were found in his personal notebooks. Others described Jeanne — the inspiration for Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal — as a “lecherous animal” and “guttersnipe.” The poet himself described his life’s love as “an impassive, cold goddess, cruel, hard, and deceitful, so sensual yet so remote that one can only worship the image of her indifferent and destructive sexuality.”

That’s the poetic ranting of the truly inspired syphilitic.

Step 2: Seek out a doctor who will treat your disease with a variety of untested and unreliable methods. Joyce was prescribed a mix of arsenic and phosphorus; Alphonse Daudet, a nineteenth-century French short- story writer, sought refuge in a sanatorium where he was suspended from his jaw and upside down from his ankles; Gustave Flaubert described his treatment of “mercury and ever more mercury” over the years.

No matter your remedy, you will have to endure much pain and suffering for the sake of art, and also because syphilis has no cure. But it’s not all bad, because your suffering will endear you to women and famous friends alike. Daudet would have been nearly lost to history if famous friends like Marcel Proust hadn’t observed his decade-long suffering, immortalizing him in verse: “This handsome invalid beautified by suffering, the poet whose approach turned pain into poetry.” The French painter Nicholas Poussin scored himself a doting wife and permanent nurse: his doctor’s daughter.

Alternatively, if you’re uncomfortable with doctors you can forgo treatment all together, like Arthur Rimbaud. But that will definitely cut into your ten to twenty year window of “frenetic mental activity.”

Step 3: This is the most important step; it’s time to work the disease into your novels, poetry or paintings. There are a variety of ways in which your suffering can be used to artistic ends: satire, celebration, metaphor, and sheer overarching madness.

Literature before the mid-eighteenth century did not shrink from syphilis. In Shakespeare, Voltaire, Swift, and many others, explicit representations of the disease abound without tiresome moralizing prose. Shakespeare used the clap (it’s unknown whether he was a sufferer) to comedic ends in Troilus and Cressida (1603), satirically rhyming: “Till then I’ll sweat, and seek about for eases/And at that time, bequeath you my diseases.”

After the eighteenth century, not even the Marquis de Sade could bring himself to directly name the disease in his racy La Philosophie dans le boudoir (1795); he preferred euphemisms like “un des plus terrible véroles qu’on ait encore vue dans le monde” (the most terrible pox the world has seen) to describe his affliction. Circuitous description and buried metaphor became standard. In Guy de Maupassant’s Bed 29 (c. 1880), an entire short story about a woman confined to a syphilis ward, not a single character ever utters the forbidden word. Instead, reference to the disease is found solely in Maupassant’s scenic descriptions — a single sign in the hospital reads “Syphilitiques.” Similarly, in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1857), the calling card of contagion appears only as metaphor, a blind vagabond meant to embody Emma Bovary’s voracious sexual appetites. The beggar a curious hat — a beaten and dirty “un vieux castor défonce” (literally translated “an old beaver”). Beaver metaphors never go out of fashion.

Painters referenced the disease in a similarly understated manner. Édouard Manet and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, both victims of the clap, toyed with contagion’s presence but never acknowledged it directly. They both painted a bounty of prostitutes, but none carry the obvious markers of disease. There are hints, of course; the black outlines contouring the body of Manet’s famous Olympia and the wretchedly contorted bodies that dance across Toulouse-Lautrec’s canvases all suggest the disfiguration of infection.

If subtlety isn’t your thing, you can always opt for a tortured reference or simple celebration. Baudelaire preferred the latter, proclaiming that, “On the day that the writer corrects his first proof, he is as proud as a schoolboy who has just caught his first pox.” He added in The Pagan School that “a frenzied passion for the art is a canker that devours the rest!” Joyce wasn’t nearly so enthused by his impending fate, feeling a bit more conflicted about the onset of debilitating and incurable symptoms. In The Sisters, a story in Dubliners, Joyce’s young narrator remarks on “paralysis…some maleficent and sinful being. It filled me with fear, and yet I longed to be nearer to it and look upon its deadly work.”

If none of these approaches satisfies your particular brand of genius, you can go diving off the deep cliffs of your unconscious, spelunking into the recesses of your now deranged mind. This method is often a favorite of painters: Vincent van Gogh and Francisco Goya painted disturbing scenes that might have been, in part, the result of their unraveling mental states. Van Gogh painted imaginary stars during his stay in an insane asylum. Goya experienced unusual moods, writing of “raving with a humor that I myself cannot understand.” His early paintings — largely portraits of the Spanish royal family — gave way to darker subjects that explored the subconscious, death, and dismemberment in terrifying ways. Remember, however: These guys painted a lot of stuff before they descended into syphilitic psychosis, and nobody can remember any of it.

During this long and excruciating process, let your spirit be buoyed by the knowledge that your very actions are literary. Thomas Mann’s novel Faustus (1947) tells the tale of Adrian Leverkuhn, a deeply intellectual composer who wishes for nothing more than to achieve greatness. Leverkuhn strikes a bargain with the devil: he intentionally contracts syphilis to intensify his expressive inspiration through derangement. (Note: best not to read the end of the book. Unless you’re really interested in the Apocalypse.)

Step 4: Finally, die a fitful and likely painful death, preferably before you reach your 50th birthday. Those were a good 10 to 20 years, right?

Previously: Cristina Scuccia and Our Enduring Love for Singing Nuns

Stassa Edwards is a freelance writer and PhD candidate living in the Deep South. For more of her misguided opinions, you can follow her on Twitter.