“To Survive in Women’s Sports, You Need to Be Somewhat Closeted”: An Interview With Kate Fagan

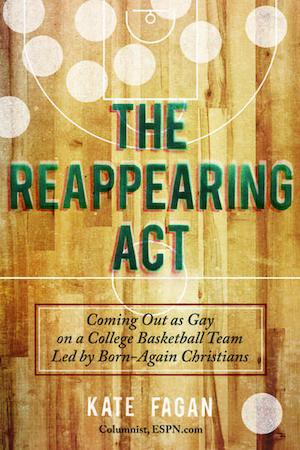

From 1999 to 2004, Kate Fagan played Division I basketball for the nationally-ranked University of Colorado Buffaloes. She’s now a reporter for ESPN. Her book, The Reappearing Act, out this week, chronicles her two-year coming-out process at Colorado, when she was a starting guard and a member of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes.

Your book covers a lot of ground. Can you break it down for anyone not familiar with your story?

It’s really a coming-of-age tale. It has the backdrop of big-time sports, Christianity, and sexuality as well. It’s about a two-year period in my life when I’m participating in the Fellowship for Christian Athletes and going to bible study, and during this time I meet a woman who makes me recognize that certain feelings of otherness that I’ve always had actually mean that I am gay. So I’m caught in this web — I was identifying as a Christian at that time but also wanted to tell some of my closest friends that I’m gay, and I try and take the readers through all of those struggles as I try to accept myself.

I think a lot of people would be surprised by how hesitant you were to come out — the conception of women’s sports is that it’s a more forgiving environment for gay women. Can you speak to that a little bit?

There really is a myth out there that women’s sports is some sort of lesbian paradise, because so many female athletes and coaches are assumed to be gay, but over the years, there has been a really disturbing pattern of closeting and fear within women’s sports. And when you live within it, you see how everybody else is acting and you really learn to feel that being gay is wrong, and that fulfilling the stereotype and being a lesbian athlete is something to be ashamed of. And all of these issues play out in women’s sports, but I don’t think we talk about them enough, because women’s sports in general doesn’t get talked about enough. People don’t stop to think about who does the hiring in women’s sports. It’s usually straight white men, the Division I athletic directors.

I saw you used this phrase in an interview recently — “the myth of tolerance” — I think that covers it. There’s one out female college coach in the country, right?

There are 351 Division I women’s college basketball coaches, and about half of them are women, and there’s one openly gay coach. And there are dozens and dozens who live in the closet. The glass closet. It’s not that they’re not out to a small circle of people, but they’re not willing to mention their partners in their media guide or speak about it openly for fear that it will affect their ability to get hired, and for fear that it will affect their ability to recruit. And there are a lot of young assistant coaches getting into the game who are learning that behavior as well. They are learning that to survive in women’s sports, you need to be somewhat closeted. It’s a very painful way to live.

Can you explain that term, the glass closet?

I think it’s usually used when talking about celebrities — you know, Anderson Cooper for a long time, the media would say, he’s in a glass closet, meaning, like, everybody can see and everybody believes that they know that you’re gay, but you yourself are you not actually saying those words out loud. You’re still in the closet, but you’re actually not hiding.

On your team at Colorado, did you all understand that your coach, Ceal Barry, was a lesbian, but it was never talked about? What was that dynamic like?

She’s absolutely a prime example of living in a glass closet. We all knew, and at various times she’d have different partners. It was something we’d talk about among each other, in a very whisper-y, secretive way, but it was never, never, never open. She would never introduce us to somebody at a banquet or at an event. It was very much like the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” And I believe that that model was and still is replicated on hundreds of college campuses across the country.

Are you seeing a shift in that? I know you profiled [WNBA star] Brittney Griner last year, who’s had this approach where you control your own narrative — she’s been so out there, doing her book and her tour and talking about it so openly. Do you think we’re going to see more of that?

I do think that Brittney’s story and the way she’s talking about it, it definitely represents a shift in terms of how we’ll see female athletes and male athletes, like Derrick Gordon at UMass, in how they want to live their lives. They want to live openly, and right from the beginning, as soon as they become professionals or as soon as they get into Division I sports or college sports. They want to be in control from day one. They don’t want to start building a platform on lies and omissions. I definitely think that’s the way we’re going for athletes, and for female athletes who then transition into a professional career and can have more control over what they do and what they say. But I don’t know that we’re in that same space when it comes to the coaching environment, especially in Division I women’s basketball. I don’t think that space believes yet that the positives of coming out can outweigh the negatives.

And Griner said that Baylor wasn’t a welcoming environment for a gay athlete.

That’s one thing that people aren’t talking about enough, I think: I don’t think Brittney was just saying that Baylor is a tough place for a gay athlete; I think she was saying that women’s college basketball is a tough place for a gay athlete. So there’s that added layer, even in her experience at Baylor. These programs are run by coaches who don’t know how to live openly. And players are internalizing that.

I played a lot of basketball growing up, and you think about all the time you spend with this very tight-knit group of girls and, for me, often all-female coaching staffs. And it seems like this environment where you’d share everything and there’s this natural closeness, but you still encountered this taboo.

The team environment is always some of the closest relationships you’ll ever have in your life. But I think in women’s sports you’re also navigating this pre-assumption that all female athletes are gay until proven otherwise. There is this assumption that women’s sports has a lot of lesbians. So I think from day one, as a female athlete, you know what the stereotype is and you work really, really hard to not be that stereotype. There’s so much pressure: let’s put makeup on before the game and let’s identify as heterosexual as we possibly can and look as feminine as we can, because you don’t want to be that stereotype. You’re constantly also negotiating that layer of identity. I don’t think male athletes really have to negotiate that. It’s not like male athletes are, like, I wanna look super manly today, so I’m gonna like put wax on my biceps. There’s that pressure for women.

And you had this added layer of Christianity over everything.

There’s so much internal angst that comes with when you’re coming to terms with your sexuality; you’re worried, first of all, that you’re gonna reject yourself, and you’re working through that. First you gotta make sure you’re not gonna reject yourself. Then you go to the next step, and you’re worried that your friends and family are gonna reject you, and you negotiate that. And when you throw religion into the mix, then you have this third layer: Is God going to reject me? Does God himself, if you believe in a God, does he not agree with who I am? And when you throw that into the mix, it can be very scary for a young person to negotiate.

Do you see yourself talking to a lot of younger collegiate athletes and this book becoming a resource for them?

That is my fundamental hope for this book, is that it tells a story, and hopefully an easy-to-digest story: that a lot of female athletes, and maybe some male athletes, are going to be able to identify with, and somehow I hope it’ll make their journey easier. I’ve already gotten a few emails from former players and women my age who say that the book helped them process some emotions that came with their coming-out experience that they hadn’t really even allowed themselves to process. I want it to be helpful. I want it to find its audience, and I think that audience is athletes — young athletes.

There’s that scene where the recruit’s mother asks you if the coaching staff “has any dykes on it” — I think that part, the recruiting and the pressures coaches feel is just not really remarked upon at all.

We talk about it so infrequently. And that was 10 years ago. I think 10, 15 years ago we were still in a place where people still felt they could use really overt, homophobic language in the recruiting process. Things like that would happen. I think now we’re in a place where everything’s become coded, so people will say, “We have a family atmosphere here. We’re family, my kids are running around.” It’s through a coded language. And it’s not like there’s a media watchdog for this. There’s not enough journalists who are, like, this is important and let’s get to the bottom of it, like there are in men’s sports. The bottom line is that women’s sports don’t make that much money, if they make money at all, and they don’t move in ego as much as some men’s sports do. So why dig into this issue and put out a story where we’re not going to get as many clicks as we would with an everyday story about men? We haven’t cleared that hurdle.

I guess part of that, too, is that the casual understanding is kind of like, “haha, the WNBA is the gay league,” and it’s not taken seriously in that way.

Before you could even get anybody to listen to what you’re saying, and get into the nuance and some of the layers that female athletes and, in turn, I think all female athletes experience, it’ll be dismissed, out of hand, like you said: haha, a bunch of lesbians playing women’s sports, what do they have to complain about? It’s a really hard time to get people to actually stop and think about how all these issues play out.

I’m curious about your understanding of how the WNBA has dealt with that reputation over the years. Do you think they’re embracing it?

I think they’re doing a better job of embracing it. I’ve said a bunch of times lately: I think in the past it sort of seems like they’ve cherry-picked players who represent, you know, “traditional” femininity. And that’s not an accurate reflection of the environment when you go to a WNBA game. You go to a game and you see a lot of their fan base is LGBT, a lot of African Americans, a lot of older people. I think the WNBA has shied away from speaking to its LGBT fanbase and engaging its LGBT fanbase. They have what I think are outdated concerns about what that will mean to the “family” — the heterosexual families they do sell tickets to. So, I think they’re definitely doing a better job in the last couple years about supporting LGBT pride and being having their brand in parades, but I do still think they need to fully, fully engage with that segment of their fan base. I think those people are ready to embrace the WNBA, but they want to be seen.

I think they’ve done an interesting thing where they’ve embraced these two extremes of representation in the league: the “heartthrob” Skylar Diggins, and then, I guess, the “butch” Brittney Griner, and there’s not really an in-between there.

Yeah, and there’s actually so much overlap between Skylar and Brittney. I think you’re right, I think the WNBA is still searching for a common theme and then how to market that common theme. They said last year that they’ve discovered this common theme where the people who attend WNBA games all think progressively about gender. But when you break that down, like, what does that mean? Obviously, fathers are going to want their daughters to have the same opportunities, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re progressive about LGBT issues. So I’m really interested to see what the WNBA’s going to do about finding a common thread in the market and then very smartly pitching and selling to that thread.

In the book you talk about coming out professionally, once you’d pursued and established a career as a sportswriter. Can you talk about those two experiences: coming out in the sportswriting world versus coming out to college basketball team?

I’ve felt totally welcomed in the sportswriting world. I’ve not had any bad experiences from fellow sportswriters and from people I respect in the sportswriting world. I think part of that is I think that when I told people in college, I was coming from a place where I was really insecure and I was struggling with my own confidence and self-worth, and I had all this doubt and a lot of the ways I presented it to people was that it was this thing they were going to have to accept in me and overcome, like it was a negative. I think when I made the decision to be very open about who I am in sports media, I was coming from a place of much more confidence, and having grown my self esteem, the way I presented it was just: this is who I am, and I’m happy with it. So a lot of it came with the way I framed it, too.

What made you use the word “Reappearing” in the book’s title?

It was a very conscious choice of language. I really do feel just in the last two or three years that you can finally see all of me. I think for a very long time I struggled to develop friendships and maintain relationships. I could never maintain a casual friendship because I was always afraid of what questions would be asked. I was also very flaky — I’d cancel on dinners because I didn’t know if I’d have to deal with questions like, “who are you seeing these days?” My life has been filled with a lot of half-truths. So once I made the decision to live openly, I felt like I could really connect to people again and break down the walls that were really keeping me from being my best self. It sounds so corny, but it’s true.

Kate Fagan is on Twitter.