The Big Book of Female Killers, Chapter 1: “The Blood Countess”

by Tori Telfer

This is the first installment of “Lady Killers,” a new series.

There’s something so seductive about the word “murderess.” It’s mostly that serpentine double “s” at the end that gives the word its poisonous charm. But murderesses: we’re into them. We like them clever, glamorous, powerful, and built for a compelling Hollywood biopic — everything that the average female serial killer from the past century or so is not. Statistically speaking, the murderesses of the modern world tend to fall under similar lowbrow headings: drug problems, low levels of education, pink collar jobs held between long periods of unemployment. They’re not into torture, nor do they engage in “overkill” — or violence beyond what is necessary to end a life. They like poison, knives, and guns. Nothing fancy.

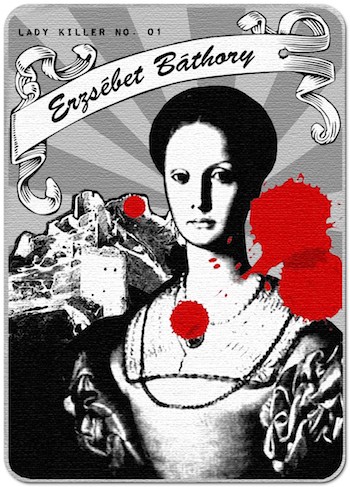

But the first known female serial killer? That’s a whole different story. She was the type of girl to really put the double “s” into “murderess”; a woman who history hasn’t been able to stop immortalizing, vampirizing, and sexualizing since records of her trial were discovered in the 1720s. I’m talking about the Grande Dame of serial killers; the OG female sadomasochist; the woman who inspired not one, not two, but eight black metal band names; the dreadful Hungarian Countess herself: Erzsébet Báthory.

Erzsébet Báthory was given the trappings of an enviable life. In 1560, little Erzsébet was born into one of the most powerful clans in Central Europe, and she had the ridiculous wealth and impeccable educational pedigree to prove it. She was a precocious kid, and knew how to read and write in Hungarian, Greek, Latin, German, and even Slovak, the language many of her servants would have spoken. She snagged a fantastically prestigious husband, she was given her own castle, and she ended up richer than the King of Hungary himself. But money and power and beauty can’t keep a bad woman down, and Erzsébet Báthory ended up walled into her precious castle with the blood of hundreds of young virgins on her hands, making this Countess the worst known female serial killer of all time.

See, all was not well in the world of little Erzsébet. She reportedly suffered terrible seizures as a child, probably due to epilepsy. And like many noble clans back in the good old days, the Báthory family had a penchant for inbreeding — after all, you have to keep the wealth in the family somehow — which, historically, has resulted in so many nobles with weak constitutions and a propensity toward madness. (When analyzing her will centuries later, handwriting experts noted signs of schizophrenia.)

Legend even has it that Erzsébet witnessed some terrible things during her childhood, including a peasant sewn alive inside a dying horse as a punishment for theft. As the story goes, little Erzsébet cackled at the sight of the peasant’s head sticking out of the horse’s body. Whether or not this particular anecdote is true, Erzsébet probably did see a good deal of violence as a child. Back then, it was considered perfectly acceptable to brutally punish one’s servants (peasants really didn’t have rights), and it’s also likely that Erzsébet would have attended the occasional public execution.

But she wasn’t just smart and freakishly unbothered by violence — Erzsébet was also really, really pretty. A portrait of Erzsébet from 1585 depicts a haunted, delicate beauty with a high white forehead (women of the time plucked their hairline to make their foreheads appear bigger) and mournful, slightly downturned eyes. It’s great fun to stare deep into those enormous eyes and imagine all the terrible things she did to young girls! But we’ll get there.

At the age of 11, Erzsébet became engaged to 16-year-old Count Ferenc Nádasdy, the son of another powerful Hungarian family; they married in 1575, after Erzsébet turned an appropriate 14. As was common back then, Erzsébet moved to the Nadasy palace during the engagement, where rumor has it that she fooled around with a local boy and became pregnant. The child was given away, all was hushed up, and the marriage proceeded as normal. In a wildly modern move, Erzsébet kept her last name, and Ferenc hyphenated his; that’s just how powerful the Báthorys were back then. Ferenc even gave his bride a home of her own — Castle Csejthe — as a wedding present. The 19-year-old Ferenc could never have anticipated the crimes Erzsébet would eventually commit in Csejthe’s dark, lonely halls.

The Nádasdy-Báthorys were now an incredibly wealthy couple, and but if they ever had a honeymoon period, it didn’t last for long. Three years after their marriage, the Ottoman Turks began attacking Hungary again, and Ferenc went off to war. He must have enjoyed the bloody pastime, because he spent the rest of his life on the battlefield, earning himself the epithet “Black Knight of Hungary” for his vicious ways.

With Ferenc at war, Erzsébet was left at home for long stretches of time — and because history loves a good dirty rumor, there are all sorts of stories about her sexual deviancy during this period, but very little proof for any of them. The book Royal Pains refers salaciously to a “well-endowed manservant” that Erzsébet liked to fool around with in Ferenc’s absence, but scholar Kimberly L. Craft argues against that in the book Infamous Lady, since none of the hundreds of testimonies against Erzsébet Báthory mention her ever taking a lover. There are also plenty of scandalous historical (and internet) rumors concerning Erzsébet’s infamous Aunt Klara, supposedly a bisexual and a sadist. As the story goes, Erzsébet liked to visit Klara’s castle during Ferenc’s long absences, where Klara would teach her niece witchcraft, sadism, and how to make love to a woman. But since Klara would have been about 60 years old by then — in an era where people died around 50 — it’s unlikely that she would have been up for that sort of energetic tutoring.

Really, we don’t have a conclusive proof for any of the sexual rumors that surround Erzsébet — just the violent ones. Letters from the time show that Erzsébet was busy keeping her family’s massive properties and accounts orderly. But the stories of late-night S&M parties persist as part of the Báthory charm. After all, a bored, beautiful, unsatisfied woman filling her empty days with sex as her husband skewers Turks — is there anything more pleasingly dramatic?

Not that Erzsébet was terribly in love with Ferenc. Their marriage was primarily a business arrangement between two powerful families, and they didn’t have children for the first ten years of marriage, though maybe it’s because Ferenc was gone for most of it. Kimberly Craft points out that that Erzsébet was probably abused by Ferenc — in those days, it was acceptable for men to make their wives “submit” behind closed doors — especially if Ferenc resented her for having a child with another man.

Still, Erzsébet and Ferenc definitely found time to bond over one mutual interest: torturing young servant girls.

Ferenc was a bloody guy already. After all, you don’t get a nickname like “the Black Hero of Hungary” without viciously skewering a few enemies on your way to the top. (Royal Pains mentions that Ferenc liked to throw two Turkish prisoners into the air at the same time and, um, “catch” them on the point of two swords.) And Erzsébet was already known for her fits of rage. So battle-hungry Ferenc introduced his young bride to the ways of torture, Black Hero-style, resulting in a long-distance relationship that was a little less “staring at the same moon” and a little more “stabbing people at the same time.” Ferenc taught Erzsébet a fun trick called “star-kicking,” wherein a piece of oiled paper was inserted between the toes of a disobedient servant and then set on fire. He also bought her a set of claws that could be fitted over one’s hand for slashing the servants’ flesh; once, he reportedly covered a young girl with honey and forced her to stand outside to be stung by insects. In short, Ferenc was a great source of inspiration for an impressionable young sociopath.

But Ferenc wasn’t Erzsébet’s only sparring partner. At some point around 1601, a mysterious woman named Anna Darvolya joined their household. Locals described her as a “wild beast in female form,” and she was rumored to be a witch and/or Erzsébet’s lesbian lover. Whatever else, she was definitely a sadist. According to trial transcripts, she’d beat the girls 500 times on the palms of the hands and the soles of their feet, or she’d “tie their hands backward” and hit them “until their bodies burst.” Anna died around 1609, just before Erzsébet’s bloody crimes were brought to trial, but she may have been the worst thing to happen to the Báthory servant girls since the whole peasants-not-having-rights thing; the other servants claimed that after Anna’s arrival, “the Lady became more cruel.”

Servant girls died occasionally at the Báthory-Nádasdy household, but it was nothing worth raising a royal eyebrow over. After all, in the eyes of the ruling classes, these young peasant girls were practically disposable. And Erzsébet knew she was above the law — in fact, the King of Hungary had been forced to borrow money from the Báthory-Nádasdys so many times that Erzsébet was untouchable. (At the time of Fernec’s death, the King owed him almost 18,000 gulden, a practically unpayable debt.) Tucked away in her craggy castle on a hill, Erzsébet could pretty much do whatever she wanted.

This isn’t to say that nobody noticed anything icky happening to Erzsébet’s servants. In fact, the local pastors began to grow suspicious when Erzsébet kept asking them to perform funeral rites for servant girls who’d died of “cholera” or “unknown causes.” At one point, they even heard a rumor that the oversized coffin they’d been asked to bless (it was closed, always closed) housed three girls inside. The rumors got so bad that one of the pastors denounced Countess Báthory from the pulpit, saying, “Your Grace should not have so acted because it offends the Lord, and we will be punished if we do not complain to and criticize Your Grace. In order to confirm that my words are true, we need only exhume the body [of the latest dead girl, to prove she was beaten to death].” The Countess stormed out of the church, and eventually Ferenc managed to appease the ministry. The allegations against Erzsébet slowed — for a while.

It was after Fernec’s death that things really started to get scary.

When Ferenc died in 1604, Erzsébet was 44 years old, and losing her looks. She may have found it difficult to manage such extensive property and staff without the quick income from Ferenc’s Turkish spoils; she may have recoiled in horror at the aging process; maybe a latent tendency toward schizophrenia, from that infamous Báthory inbreeding, began to rear its head during Erzsébet’s later years. Either way, what had started as a shared hobby with Ferenc and Anna quickly turned into a full-blown obsession, and Erzsébet became fanatical about torturing and killing young girls. She liked them young, strong, and unmarried — 10- to 14-year-old peasant children from the towns surrounding the castle, expendable bodies that nobody important would miss.

As always, Erzsébet didn’t work alone. Along with Anna Darvolya, Erzsébet gathered a gruesome torture squad of three old women and one boy: her children’s nurse, Ilona Jó; an old friend of Ilona Jó’s, who went by Dorka; an old washerwoman named Katalin; and a disfigured young boy known as Ficzkó. According to the trial transcripts, Dorka lured the most peasant girls to the castle — attracting them “with the promise that they would either marry a merchant or that they would be brought somewhere as a chambermaid” — where they’d eventually meet a gruesome end. Anna, Dorka, and Ilona Jó were the most vicious of the torturers and took pride in their gory skill sets. Ficzkó helped, but he was awfully young (documents from the time refer to him as a “child”), and Katalin appears to have been the most soft-hearted of the bunch — she’d participate in the torture because she had to, but she also snuck food to the broken-down girls when she could.

According to the trial transcripts, the torturing would usually start with irritation over a servant girl’s mistake. Maybe the girl would miss a stitch, causing the Countess to turn on her with a snarl. She’d begin by slapping, kicking, or punching, and the punishment often fit the “crime”: misbehaving sewing girls would be poked with needles; a girl who stole a coin got that same coin heated in the fire and branded into the palm of her hand. Erzsébet would prick the girls’ fingers with pins, saying, “If it hurts the whore, then she can pull it out.” Psych! If the girl did pull out the pin, Erzsébet would cut off her finger.

If the torture stopped there, it was a pretty good day for the servant girls, but Erzsébet’s craving for violence was rarely satisfied with pinpricks and the occasional severed finger. According to Ficzkó, girls would be tortured up to ten times a day in the Countess’ torture chambers — she had a specific place for torturing girls in each of her many castles — and the brutalities were absolutely inhuman. The torturer squad would heat irons and burn the girls all over their body, including their genitals. Erzsébet forced girls to stand naked outside and poured cold water over them until they froze to death. Once, she put her fingers inside a girl’s mouth and tore her face apart. There were also reports of pincers used to rip out the girls’ flesh, along with rumors of cannibalism — force-feeding the girls pieces of their own bodies or the flesh of their fellow servant girls. Dorko liked to cut the girls’ fingers with shears. Anna preferred her 500 lashes. And Erzsébet liked it all. She’d strip the girls naked before she beat them, and once bit a piece out of a girl’s face and shoulder when she herself was too sick to get out of bed. Endless beatings, starvation, knives, cannibalism, branding, and maybe even an Iron Maiden — these were the ways the Báthory servant girls died.

Wherever Erzsébet Báthory traveled, she killed servant girls. “Anywhere she went,” confessed Ilona Jó, “she looked immediately for a place where they could torture the girls.” She’d kill girls in her carriage on the way to social events and have their bodies buried on the go. The killing was turning into some sort of deep psychological need, exacerbated by social stress. A witness at Erzsébet’s trial claimed to have seen shackled servant girls who told him that “their mistress could neither eat nor drink if she had not previously seen one of the virgins from amongst her maids killed in a bloody way.”

One of the most enduring rumors about Erzsébet says that she bathed in blood to preserve her beauty. This story goes like this: one day, when a servant girl messed up some aspect of Erzsébet’s toilette, Erzsébet slapped the girl so hard that blood spattered Erzsébet’s hand (or face). After washing off the blood, Erzsébet noticed that her skin looked younger than it had before. This lead to an obsession with soaking in a tub of virginal blood during top-secret 4 a.m. baths.

Unfortunately for the vampire-obsessives among us, this is probably not true. None of the servants who testified against Erzsébet mention anything about the Countess bathing in blood. In fact, what they do mention is that so much blood was spilled during torture sessions that you could scoop it off the floor. So Erzsébet didn’t seem too concerned with saving — much less bathing in — the precious blood that poured from her victims. In fact, the first mention of her blood baths appears over a century after her death, in a 1729 book by the Jesuit scholar László Turóczi, called Tragica Historia, which he wrote after discovering the Báthory trial transcripts.

It’s easy to see why the blood bath rumor has persisted, though. Not only is it a compellingly creepy image, but it solves the distressing idea of a murderess who kills just because she’s a killer. If Erzsébet killed those girls in order to preserve her looks, we don’t have to worry about the question of evil in the Báthory case. Vanity is a much more accessible reason for the crimes, since all that bloodshed simply comes down to a misguided desire to look extra-good for boys. An Erzsébet who bathes in blood is actually much safer than an Erzsébet with an anger problem.

But be not disappointed at the lack of blood baths. Plenty of blood was shed at chez Erzsébet, so much that the walls were spattered with it and, according to Ilona Jó, Erzsébet sometimes had to stop mid-torture and change her shirt because it was so drenched (ugh). While her affinity for stripping her young maids naked does seem to hint at some sort of sexual disorder, and her dealings with the occult may have occasionally focused on preserving her youth, it seemed that what the Countess truly liked was pretty straightforward: to absolutely destroy the body.

Until now, Erzsébet was still killing peasants, which was a pretty safe bet. Parents would sell their child for a lump sum to work as a servant, and if the child died of “cholera” — Erzsébet’s go-to excuse — the family could never press charges against the noble, no matter how suspicious the circumstances. Sure, Erzsébet and her cohort were killing so many girls that they couldn’t even bury them all — at one point, dogs uncovered some of the hastily-dug graves, and you can imagine what they dragged around the courtyard — but Erzsébet remained unassailable. Remember, the Crown owed her money. But like many a serial killer after her, the Countess grew reckless, which proved to be her downfall.

Tired of peasant girls — or perhaps running out of live peasant girls — Erzsébet decided to harvest the daughters of lesser nobility. The suggestion may have come from her Lady Steward, Erzsi Majorova, who was also a witch. By then, cruel Anna Darvolya had died, and Erzsébet was taking advice from Erzsi. Rumor has it that Erzi suggested the potent blood of noble girls, since peasant blood wasn’t staving off the Countess’ inevitable aging. Or maybe the Countess just wanted a change in her regular lineup. But how to lure these bright young things over to the castle? Peasant parents were easy to deal with, but the nobles would definitely notice if their daughters went missing.

Eventually, Erzsébet hit on the brilliant idea of pretending to open a finishing school for young women, called a Gynaecaeum. She ushered in a gaggle of aristocratic youngsters and, well, finished them. When wealthy parents began inquiring about the state of their offspring, Erzsébet invented a truly crazy cover-up: one of the girls had been really jealous of the other girls’ jewelry, said Erzsébet, and so she murdered them. For their jewelry, get it? Then, after realizing what she’d done, the gem-hungry girl committed suicide. OKAY?

Needless to say, the Countess wasn’t convincing anyone by this point. Rumors were spreading like wildfire — people had actually heard the girls in the Gynaecaeum crying, and townspeople were beginning to report seeing the Countess’ black-and-blue servant girls out in public with bandaged faces and hands. But most importantly, noble girls had been killed. This was enough for the King to move against bloody Erzsébet.

In February 1610, the King ordered his Palatine, György Thurzó, to begin an investigation against Countess Báthory. It’s worth noting that this wasn’t a simple case of good king vs. evil lady — the King still owed enormous sums of money to Erzsébet, and if she were locked up, his debts to her would be conveniently cancelled. So Thurzó began collecting testimonies against the Countess.

You can read the witnesses’ testimonies today — they’re translated in the appendix of Infamous Lady — but you’ll want to wait until after lunch. Hundreds of people affirmed the rumors of terrible violence against the Báthory servants, placing the number of dead girls around 175 or 200. Unfortunately, few had actually seen anything conclusive, so the investigation dragged on for months. By December, Thurzó was almost ready to act, but before he could arrest such a powerful woman, he had to be completely certain that she was guilty. So Thurzó met with the Countess in person, where she smoothly denied all the allegations, saying that the girls had merely died of an epidemic — oh, and that whole murder-suicide-jewelry-thief thing. He then returned with the King himself, but Erzsébet — getting desperate? — tried to poison them with a magical cake, courtesy of her go-to witch, Erzsi. Something was rotten in the state of Csejthe, despite the cool, glamorous composure of its Countess. Everyone knew it.

On the night of December 29, 1610, Erzsébet and Erzsi went outside to cast a spell, which their scribe later revealed to the court. It began, “Help, oh help, you clouds!…Send, oh send forth, you clouds, 90 cats!” These cats were instructed to “chew to pieces the heart” of those causing the Countess grief. Erzsébet then retreated inside to begin, we can only assume, her regular blood-soaked nightly routine.

Later that night, Thurzó crept toward Castle Csejthe, accompanied by a party of armed guards. It didn’t take them long to gather evidence: they found the dead body of a mutilated girl near the entryway to the castle, and two more girls lay dead or dying right inside the castle doors. The sound of screaming led the men to one of the torture chambers, where they caught Countess’ cohort of torturers at work. It’s unclear if Thurzó actually caught the Countess in the act, but they had their evidence — she was responsible for her employees’ actions, at the very least — and they wasted no time in dragging her out of the castle. Later, Thurzó wrote to his wife that they’d discovered even more girls “hidden away where this damned woman prepared these future martyrs.”

A grand total of 306 people testified against the Blood Countess. Ilona Jó, Dorka, Katalin, and Ficzkó were all tortured, and confessed to their crimes in detail, pointing to Erzsébet as the source of it all. While those four claimed the number of dead girls fell around 36–51, another witness (a young servant girl named Szuzanna) said that the countess had killed 650 girls and kept their names written in a little ledger. To this day, no one knows for sure how many girls Erzsébet Báthory killed.

Ilona Jó, Dorka, and Ficzkó all received the death sentence. Since Ilona Jó and Dorka had been personally responsible for so many “serious, ongoing atrocities perpetuated against Christian blood,” their fingers were torn out by heated iron tongs before they were executed and thrown into a huge bonfire. Because of his youth, Ficzkó was beheaded and then burned. Katalin, who appeared to have shown some mercy to the girls, was sentenced to be jailed “until perhaps other more clear evidence is given against her.” (Kimberly Craft speculates that she may have been quietly released later.)

And as for the Blood Countess herself? She was still too far above the law to receive the death penalty, as much as the King or the court may have desired it. She was never brought in for interrogation — torturing such a high-standing member of the Hungarian nobility to get a confession would have set a dangerous precedent. And while Thurzó and the King tried to figure out how to condemn her, she willed her lands to her children, meaning that the King wouldn’t get to keep the extensive Báthory estates even if Erzsébet was executed.

Eventually, Thurzó condemned the Countess to lifelong imprisonment in her own bloody Castle Csejthe, pronouncing, “You, Erzsébet, are like a wild animal. You are in the last months of your life. You do not deserve to breathe the air on earth or see the light of the Lord. You shall disappear from this world and shall never reappear in it again. As the shadows envelop you, may you find time to repent your bestial life.”

The King’s debt was cancelled, and all legal documentation about the trials was sealed. The Countess was walled into her own castle, with just enough space between the bricks to pass food through. Parliament decreed that “the name of Erzsébet Báthory would never again be spoken in polite society.” And the towns around Csejthe grew quiet for the next 100 years.

But despite the court’s best efforts to act as though Erzsébet Báthory had never lived, her story spread and spread once the trial transcripts were rediscovered in the 1720s. Today, the Blood Countess is a hugely popular figure in the world of horror, gore, and sexy vampires, featured in everything from a Venom single (notable lyric: “Couuuuuntess BAAAAAATHORY”) to poetry, novels, and films. Historian Raymond McNally has even argued that it was Erzsébet who inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Run a Google Image Search on the Countess and you’ll see just how sexualized her legend has become — you’ll find everything from manga of the Countess sporting bloody nipple clamps to fan art featuring a nude Erzsébet reclining seductively in a bathtub full of — well, you know. As scholar Christina Santos wrote in a paper on Erzsébet, “the “monstrous” characterization of Báthory is unfairly and predominantly linked to her sexual deviance: her suspected lesbianism, her marital infidelities, and an overall deviation from the proscribed role for women in her society and culture.”

Her story has a sick glamour, sure. Who isn’t drawn to the idea of a vampiric Countess with long black hair and penchant for ripping apart lithe nudes? She’s a seductive antagonist, worthy of the serpentine sound of murderess. But all this talk about sex and beauty distracts from the fact that according to historical documents, Erzsébet may have simply been the most frightening and least pretty thing of all: a killer. The fan art that features a voluptuous Erzsébet with blood-splattered cleavage isn’t scary — what’s scary is that 1585 portrait of Erzsébet. What’s scary is staring down the blank innocence in those big, 400-year-old eyes.

Countess Erzsébet Báthory died on August 22, 1614. According to a letter by Thurzó, the last thing she did was lay down in her bed and sing, beautifully. She was buried in holy ground, but her body was later removed, after residents complained, and taken to the Báthory crypt. That crypt was opened in 1995. No trace of Erzsébet was found.

Top art by Maya West.

Tori Telfer is a writer from Chicago prone to nightmares, writing about creepers, and snatching ideas for stories from happier dreams. “Lady Killers” will appear on The Hairpin regularly. Read more of Tori’s work at toridotgov.com.