Fifty Shades of Brontë

by Alison Kinney

She describes him as “full of an interest, an influence that quite mastered me, — that took my feelings from my own power and fettered them in his.”

He tells her, “[Y]ou please me, and you master me — you seem to submit, and I like the sense of pliancy you impart; and while I am twining the soft, silken skein round my finger, it sends a thrill up my arm to my heart. I am influenced — conquered; and the influence is sweeter than I can express; and the conquest I undergo has a witchery beyond any triumph I can win.”

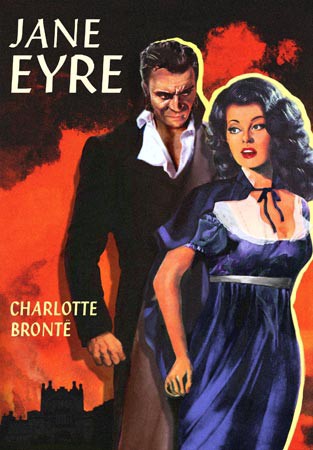

So speak the characters of an 1847 novel about a teenage girl’s liaison of submission and provocation with a sensuous, violent man twice her age: Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

What with the women’s lit market popularizing all things nineteenth-century and English, on one hand, and BDSM, or what passes for it (NSFW link) in Fifty Shades of Grey, on the other, it’s no surprise that Brontë’s novel should be getting the E.L. James treatment: in Jane and Her Master (rereleased in 2012 by Silver Moon Books), and in the 2013 Clandestine Books edition of Jane Eyre, which interpolates 30,000 words of racy text, including “explosive sex,” into the gothic original. Yet the S&M revisions only highlight the transgression of Jane Eyre’s original, risky eros. Why bother to reinvent it at all?

Possibly because, since it first broke upon a scandalized public (few readers could believe that a nice maiden lady had written it), Jane Eyre has been lionized, analyzed, neutralized, and given to countless impressionable preteen girls for their birthdays.

When I was 10 years old, I identified with its tale of a plain but spunky girl who uses her smarts to win love and happiness. (That story’s in there, but it’s not all there is.) In Women’s Studies classes, I saw a feminist manifesto about a fiercely independent, free-thinking young woman who demands equality, respect, and emotional, spiritual, and intellectual fulfillment. (Which it also is, but.) For me and many other women, it reaffirmed our belief in our right to live, work, and be loved on egalitarian terms.

Once, like Jane, I had an unpolluted memory and little experience with the petty dissipations of the world. Now that I am 39, Rochester’s age, Jane’s choice of a manipulative, predatory, married boss as her soul mate; the seething sexual provocation and coy submission; and Rochester’s domination of Jane all look darker, scarier, and more complicated to me. But also happier: a different kind of self-determinism and feminism is going on. Now that we impressionable 10-year-olds have grown up, and some of us have bookworm daughters of our own, it’s time that we talk frankly about Jane Eyre’s sadomasochistic overtones within a literary culture that popularizes but confuses issues of violence, love, and, above all, consent and coercion.

For the past 167 years, Rochester and Jane have been playing a game of consensual domination and submission. He coaxes her, “Look wicked, Jane; as you know well how to look: coin one of your wild, shy, provoking smiles; tell me you hate me — tease me, vex me….” From Jane:

I knew the pleasure of vexing and soothing him by turns; it was one I chiefly delighted in, and a sure instinct always prevented me from going too far: beyond the verge of provocation I never ventured; on the extreme brink I liked well to try my skill. Retaining every minute form of respect, every propriety of my station, I could still meet him in argument without fear or uneasy restraint; this suited both him and me.

To take the metaphor to its logical conclusion, Jane is a spirited, self-aware, straight-talking submissive who yields to Rochester’s domination, or tops for his pleasure, within the free and loving boundaries of their relationship. (She might better be described as a switch, but, “[A]fter all my task was not an easy one; often I would rather have pleased than teased him.” You don’t go around calling somebody “master” for no reason.) Rochester tells her, “[I]t is your time now, little tyrant, but it will be mine presently: and when once I have fairly seized you, to have and to hold, I’ll just — figuratively speaking — attach you to a chain like this,” and shows her his pocket restraints.

To be clear: the BDSM isn’t the scary part. For Jane, happiness and even physical well-being consist of serving, obeying, piquing, and entertaining her beloved master. She thrives in intelligently resisting, teasing, or yielding when she likes, with a partner who regards her as his equal and his likeness. The trouble starts when Rochester abandons all the rules of their agreement and starts abusing her instead.

BDSM communities come in all configurations of genders, sexualities, numbers, and priorities. Although I’ve found the feminist writers most instructive (Dorothy Allison’s 1994 collection Skin was my entrée), all BDSM communities emphasize communication and explicit consent. Their insistence on consent, to the point of contractual obligation, ought to be instructive to mainstream feminist thought about sex and violence. These communities actively reject the kind of casually predatory brutality that is far too common in vanilla encounters. By their reckoning, the infliction of pain or domination without permission, feedback, and safety guarantees isn’t even BDSM anymore: it’s simply abuse.

But just because S&M has gained some mainstream traction doesn’t mean that its safety practices have also been promulgated. As many writers have pointed out, Fifty Shades of Grey isn’t really about S&M at all, but just eroticized violence that justifies itself by referencing a wildly misunderstood subculture. Although BDSM is often about eroticized aggression, it is always about eroticized consent, eroticized communication, and eroticized safety. This confusion of mistreatment with BDSM can be disastrous for women.

Charlotte Brontë knew the difference between power play and compulsion; she wrote a masterpiece how-to manual for women who desire to be submissive to do it safely, and to know when to get out. While Jane may be an excellent bottom, Rochester reneges on his responsibility, as the dominant, to protect her: he violates the rules, her trust, her integrity, and her freedom. Jane’s fear of being “forced…to be his mistress” isn’t just about the degradation of her social and financial position: she’s talking about sexual assault. When Rochester sneakily promises to install her in his whitewashed villa in Marseilles and not touch her, she calls bullshit. Or, rather, “sophistical.” Then:

His fury was wrought to the highest: he must yield to it for a moment, whatever followed; he crossed the floor and seized my arm, and grasped my waist. He seemed to devour me with his flaming glance: physically, I felt, at the moment, powerless as stubble exposed to the draught and glow of a furnace….

It is not OK to be forced. It is not OK to be lied to about one’s partner’s wife being locked in an attic. (For that matter, it’s not OK for anybody to blame the wife. “It is cruel — she cannot help being mad.”) Brontë makes it clear that Jane needs to disobey, cut off all contact with her would-be rapist, and save herself. But she also understands that escaping an abusive partner can cause complicated, devastating emotions. “I had no solace from self-approbation: none even from self-respect. I had injured — wounded — left my master. I was hateful in my own eyes.” Having been terribly hurt, Jane shrinks from inflicting any harm herself.

More importantly, in leaving him, Jane knows that she must shelve her erotic identity and the freedom to express her desire in the way that feels most natural to her. She runs away not only from her fear of being forced to be his mistress, but also from her fear that this is precisely what she wants: “To have surrendered to temptation; listened to passion; made no painful effort — no struggle; — but to have sunk down in the silken snare; fallen asleep on the flowers covering it; wakened in a southern clime, amongst the luxuries of a pleasure villa: to have been now living in France, Mr. Rochester’s mistress; delirious with his love half my time — for he would — oh, yes, he would have loved me well for a while.”

“Here’s the thing about consent,” BDSM activist and author Clarisse Thorn points out: “orgasm is not consent. Physical pleasure is only the body’s reaction to certain types of stimulation. Also: sexual desire is not consent. And love isn’t consent, either…. In short: There can be pleasure, desire, and even love existing alongside real abuse. But that doesn’t mean it’s not abuse. This is as true with S&M as it is with non-S&M sex.” Deep down, Jane may long for the passion, but no means no.

Under these terms, how can a happy reunion possibly come about? Only through the complete rehabilitation of Rochester’s character and the inversion of their power relations. When his house burns down around his ears, blinding and maiming him, at first he gets madder and more self-righteous. But then, the more he feels “desolate, afflicted, tormented” by God, the more he understands what it means to suffer violence from a stronger, unrelenting, unforgiving hand. He stops blaming his unhappy childhood and his wife; unlike many abusers, he accepts the full responsibility for his maltreatment of Jane. Not only does he regret his actions, but also he tries to become a better man. He changes. And Jane gains the upper hand in their external relationship: she becomes independently wealthy! She has gained more romantic experience, rejecting the marriage proposals of yet another dominant, to whom she bluntly declares, “If I were to marry you, you would kill me. You are killing me now.” Jane and Rochester’s happy ending requires an extraordinary degree of mutual respect, honesty, and fairness.

Then they continue in their merry BDSM way, teasing and tormenting each other, having kids, writing a novel, and taking trips to London — and probably, also, to the Côte Bleue sex villa.

Those of us who love women’s literature ought to talk frankly about the consensual eroticism, and the abusive violations, between characters such as Jane and Rochester, or Anastasia and Gray. Otherwise, we tacitly assent to a world that dismisses the importance of consent, be our choices sexually normative or not. It is all right for a young reader, like Jane, to discover that her desire is to submit, to obey, or to tease — or even to be a Blanche Ingram, who “has it in her power to inflict a chastisement beyond mortal endurance.” It is all right for a woman to enjoy it when a much stronger and powerful partner painfully grapples her body, but only if she truly wants it — if the terms of equality are explicitly set and honored — and there’s a safe word. She should feel what Jane feels: “an inward power; a sense of influence, which supported me. The crisis was perilous; but not without its charm.”

Alison Kinney’s work has appeared in The Robert Olen Butler Prize Stories, The Literary Review, Salon, The Blue Mesa Review, Gastronomica, and The Inquisitive Eater. She received an M.F.A. in creative writing from The New School.