The Journey to Salvation Mountain

by Laura Yan

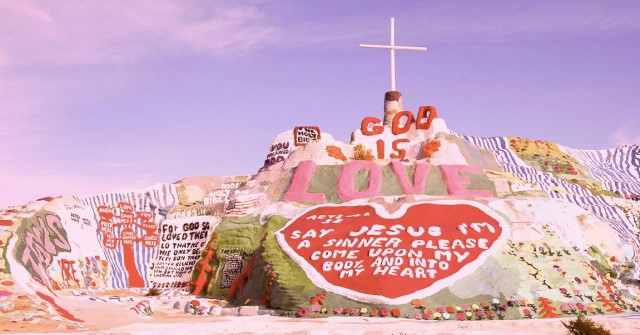

Yesterday, Leonard Knight, the man who built Salvation Mountain, died at the age of 82.

The trick is to say this exact thing, I said. What seems to be the problem, officer? And you have to call him officer.

I’m not going to call him officer, Avi said.

What about the hash? What if he checks inside the car? Cathy asked.

Everybody just be cool, Avi said. He rolled down the window.

The cop beamed his flashlight into the front seat. What’s your nationality?

I’m American but I was born in Israel, Avi said.

And your mom? He motioned towards Cathy.

I’m not his mom, she said. I’m American.

The officer checked the back of the van, shining his light on the mattress on the car floor, at the rest of us on the backseat. He waved us on. We were coming back from Salvation Mountain, the three-story folk art mountain built for God.

*

Leonard Knight built Salvation Mountain alone over thirty-something years. Leonard grew up on a farm in Vermont. He dropped out of high school and worked in the same factory as his father before he was drafted into the army. He served for a brief stint, and then returned to Vermont, where he started painting cars and playing the guitar. In 1967, Leonard came to San Diego to visit his sister, who talked often about God. To escape his sister’s talk, he went to sit in his van. But then, alone in his car, he started to recite the Sinner’s Prayer. He told the Deuce of Clubs in an interview that it happened like this: “I said it ten times, by myself, with Jesus. And tears came to my eyes. So I said it for a half hour. And I ended up crying.”

Jesus, I’m a sinner, please come upon my body and into my heart.

He was 35 and he had never believed. But that day, everything changed.

He spent years trying to spread God’s message. Churches rejected his ideas for being too simple. He prayed for a hot air balloon that would spread the message, and when God didn’t deliver it, he made his own. In Slab City, he tried to make the balloon fly with the help of the locals, but the balloon never took off.

Before he left the desert, Leonard thought he’d build one last thing.

*

Avi’s van was not very aerodynamic. There was a high wind advisory and we swerved wildly on the road, sometimes straddling two lanes, balancing in the middle. We were an odd group. Avi was our driver, a dreadlocked hippie with sharp cheekbones. Cathy, sitting shotgun, was 66, and had once bitch-slapped (her term) an offending member of Occupy in San Diego. Every so often Cathy asked Avi questions like, “What does ‘dank’ mean?” Their conversation was endlessly amusing to the backseat, which was Adám and me.

Adám (the accent mark denoting the Hebrew pronunciation of his name) was a student at UCSD and already predestined to become a Latin American traveling hippie, while I’d just returned from months of backpacking there, and was still starry-eyed for anyone who spoke Spanish and played the guitar. And there was easily forgotten Sara, a law student from Germany who was mostly quiet throughout our trip.

*

Salvation Mountain was supposed to be a small project, an eight-foot tall monument. But it grew bigger and bigger, beyond Leonard’s plans and projections. The first one crumbled to the ground after four years of work, but Leonard was not discouraged. By then, his devotion was complete. He rebuilt the mountain, this time using homemade adobe and over 100,000 gallons of donated paint.

That was the Salvation Mountain we wandered through that afternoon, a baffling and marvelous testament of faith. It loomed tall and bright in the barren landscape, declaring its message in primary colors and flower motifs. Leonard made sure that the world would see his message: God is love. But it was hard to know how many took the message to heart, and how many were skeptics like us, who found the whole thing amusing.

*

Salvation Mountain is situated next to Slab City, an RV community of vagabonds in the desert near Niland, California. Slab City used to be Camp Dunlap, a marine training base. After the naval base was abandoned, it slowly became a home to the otherwise homeless, or to people who wanted to be left alone. There was no running water or electricity or much law in Slab City. The community ran it, and it played by its own rules.

We walked through one of Slab City’s neighborhoods. It was quiet. A couple sat outside of their trailer, reading in the sun. The Oasis Club, a library and a community center that sold toilet paper and Internet access, was empty. There was something enchanting about the dry, low shrubs, the games the residents made out of scrap metal, the desolation. Somewhere, a girl with a beautiful voice sang and played the guitar.

In the summer, the desert got as hot as 130 degrees, and the 2,000 something residents that lived in Slab City during the winter (“snowbirds”) would migrate elsewhere, leaving only a few hundred. The water was so hot it would burn you. There was little to do but to look for shade and pray.

*

In Slab City, we picnicked by the hot spring. Avi got naked and submerged himself first, slathering black mud over his body and his face. It’s a great exfoliant, he said — unless it’s tar. Sara and Adam joined him, and I dipped my legs in the water, and watched half of a Band-Aid float near my feet.

I learned later that dead bodies had been found in the hot spring, sometimes while unsuspecting locals continued to soak above (bodies sink before they float). The locals used the hot spring as a public bath, gathering ground, and perhaps anything else they needed. While we dried off, a family carrying bottles of soap and shampoo slipped in the water, bathing their naked daughter. A cowboy with two mules stopped to give them water.

I took a photo of John, a caretaker of Salvation Mountain who lived in Niland — not Slab City, which he made the point to distinguish — by his army-print VW bug before we headed back towards San Diego. He suggested that we all come back for The Range, the open mic performance that happened every Saturday night in Slab City. Some of the folks are really talented, and it’s a hell of a time, he said. Though The Range mostly consisted of locals, anyone was welcome to attend.

He also told me to look up Range Hot 2014 to see if I wanted to participate. Don’t agree before you see what it is, he said. I imagined it was some sort of orgy, and then I found a video on Youtube when I got home: a bunch of people, mostly women, shooting guns and laughing in the desert, no protective goggles or earmuffs or safety in sight. It did look like a blast.

We made one more stop at the swap meet in Niland before we headed back towards San Diego. Cathy bought jewelry-making tools for a dollar each, and Avi tried to trade his weed for a hand-cranked drying machine to no avail, although he did successfully buy a machete for four dollars. Maybe it was providence that the immigration officers didn’t check the van too closely when they stopped us on the drive back.

*

We talked about faith that afternoon, about what prompted a man to spend years and years of his life building a mountain in the desert, quoting from the Bible. Maybe it was a joyous thing, or maybe, like Cathy said, it was a form of penance. In all the interviews I’d seen of Leonard, he seemed like a happy man, with bird-like eyes and a singsong voice. From what I could tell he was living in a nursing home in El Cajon, away from his mountain, his truck, his freedom.

The last time Leonard visited Salvation Mountain was in May of 2013. He hadn’t seen his creation in ten years. He was in a wheelchair, and one of his legs had been amputated. He wore a hearing device and couldn’t see very well. But his laughter came easily, and he spoke with energy.

“Let’s not get complicated with love,” he told a visitor.

Laura Yan is a freelance writer, photographer and wanderer. She tweets at @noirony.

Photo credit Brian/flickr