The Best Time I Married My Gay Best Friend in Vegas

by Liza Monroy

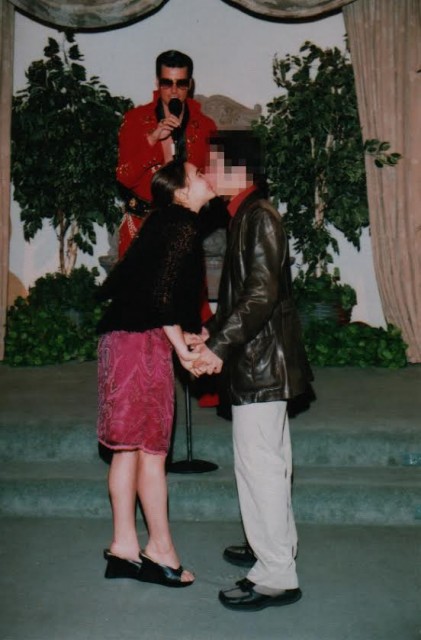

Plastic trees and fabric foliage behind the Elvis impersonator distracted me from the fact that my father wasn’t walking me down the aisle. Instead, Emir and I danced our way down, and I felt as if we were acting in a high school musical.

Elvis spun around, his black hair slicked up with grease. He was wearing oversized sunglasses and a shiny red silk rhinestone-studded jumpsuit. Our friend Omar clapped on the sidelines, snapping pictures all the while for our INS album. It was the most fun I’d had since the end of my first engagement.

“The minister is gay,” Emir said into my ear. “And I think he might know.”

“Act straighter,” I murmured back as we made our way toward Elvis.

The music and Elvis’s hip-swinging jig stopped for the vows.

“Do you promise to polish each other’s blue suede shoes?” asked Elvis.

We agreed.

“Do you promise to walk each other’s hound dogs?” asked Elvis.

“I’m more of a cat person,” I said. “But sure.”

“Yes, yes to everything, Elvis!” said Emir.

Elvis asked for the rings. Emir said we didn’t have them yet, that they were still at the engraver’s. I waited for suspicion, but the moment passed without consequences. Such were the unforeseen advantages of getting married in Las Vegas — nothing is strange.

“In that case,” Elvis said, “you may kiss the bride.”

Time slowed as Emir and I leaned in. More than anything, it was this kiss that I had been nervous about. The fact that sexual attraction had no part in our relationship was largely what made me feel so confident and secure. It was so lovely: to be married — yet to be free! All the stability of having a partner with none of the requisite obligations. We were just dipping our feet into the shallow end. The blue-suede vows had been light; the kiss I’d so dreaded turned out to be even lighter.

It was our first kiss and our last. And with that, Emir and I were officially linked by the state of Nevada. We posed for photos with the minister and Elvis, our INS photo album already coming together. Omar joined us for some of them. As the three of us emerged from the chapel, Elvis, the minister, and the receptionist waved and threw rice.

That was the beginning of a married life where the men were gay, the nights late, and the word “settle” meant hooking up with someone I didn’t consider attractive.

•••

At the Stratosphere, the Space Needle–shaped hotel casino, Emir and I ascended to The Big Shot: the world’s highest thrill ride! Thrill seekers only! And it felt like a physical manifestation of what we’d just done. We shot through the night to 1,081 feet, the wind deafening, the view magnificent and terrifying, the two of us strapped in with no chance of getting off. Going up was scary and coming down fun. Or was it the other way around? I remember screaming and screaming as we fell over the concentrated desert lights, that neon huddle of fireflies. It was over before I opened my eyes.

In the photograph of us, purchased on touchdown, Omar, furthest to the left, throws up his arms and wears a bemused smile, as if saying he had no responsibility in the matter. Then comes me, clutching the straps that hold my body to the machinery, my eyes clamped shut as tight as a newborn kitten’s, my mouth open as far as it could be. Then Emir, who is looking up. Smart Emir, who looks up to avoid looking down.

Omar left us after that, in search of a gay club. Emir and I went to the Hard Rock Casino. Our friend Mohammad had given us a thousand dollars to play with as a wedding gift, and we took it to the blackjack tables. After we were down to a few hundred, we walked past the slots with no intention of playing. I dropped a quarter into a Jefferson Airplane White Rabbit Slot Machine as we made our way out and kept walking. “One pill makes you larger/ and one pill makes you small/ and the ones that mother gives you/ don’t do anything at all…” The slot machine went crazy. We spun around. Three white rabbits.

We’d hit the jackpot.

Back in our room at the Motel 6, Emir and I crawled into our adjacent double beds a bit tipsy and too wired for sleep. We recounted the night to each other, and when we finally exhausted our stories, I pulled The Brothers Karamazov from my purse and Emir took his Harry Potter hardcover from the nightstand. I found my place. We sat up reading in bed until it was time for lights out.

•••

In the morning, the three of us got into Emir’s car. I was eager to get home, but optimistic and hopeful. Getting married had been easy. What next? I felt fearless, fierce, certain that the next two years were going to be stable and smooth. I’d always have Emir to count on. And I was going to learn so much: being married to Emir was a unique opportunity, a training ground in being someone’s partner sans the passion that accompanied sexual relationships, which would allow me a sort of detached objectivity on the marriage act. Given the absence of passion and sex, maybe I could at least wrap my mind around partnership. I’d wade in slowly and see if I couldn’t figure out enough about marriage to feel confident entering one in the future.

In the apartment that was now ours, Emir and I curled up under a fuzzy gray blanket on the couch to watch more Sex and the City. I joked that I was guilty of “alien snuggling.” That night, I drifted in and out of sleep, The Big Mom in the Sky on my mind. She didn’t need to watch from the sky to find out I was married to Emir. All she had to do was type his name into the Consular Consolidated Database system at work. And if she did? Then what? I kept coming back to the question. Was she more Visa Chief than mother? She loves me — she wouldn’t out me as an alien smuggler, if that was even what I was. Would she?

My mother was fond of reminding me I lacked judgment. My frontal lobe wasn’t fully developed, she reminded me, and it would not be until I was 25, so I should avoid making major decisions. “What if, blinded by passion, I married the wrong man?” she reminded me.

She was speaking from experience. My mom, Penny, the Visa Chief, had a whole other life before her high-powered career. Her marriage to my father originated in deception, too.

She’d met him in college, when she was 23, on board a ship from New York City to Genoa, on her way to study abroad. His name was Gioacchino Giovanni Gennatiempo; he was 35, a bachelor and a wanderer, and five years later, he would become my father. With them, unlike with Emir and me, there was traditional romance involved, a romance of cinematic proportions.

It seems fitting to me now that their romance began at sea. They were on a boat together for two weeks, neither able to exit. Over those two weeks traversing the Atlantic, they fell in love, or at least into passion. I imagine them atop that vessel, kissing on the deck at night, drinking wine, and dancing at the top-floor disco.

“I’ll bet you have a wife and kid waiting for you on the dock,” Penny said one evening as they neared the port in Genoa. I imagine they were both dreading their moment of parting by then, not wanting the ship to ever anchor.

“Te ho detto, non sono sposato,” Giovanni said. I told you, I’m not married.

Penny never attended the summer program — students and professors across Italy were on strike; classes weren’t being held. It was very Italian, il sciopero. She spent that time with her Italian love instead. Three months later, she wanted to bring him to America. My father went to an interview at the U.S. consulate, seeking a tourist visa so he could spend some time in the States with Penny.

The visa officer, someone with the same job my mother would eventually have herself, denied him. Judging from my father’s lack of financial stability, the likelihood that he would stay in the States and work illegally seemed high. The only other option to get him into the country was marriage. Penny called her parents and asked them to send her birth certificate to Italy so she could get married. They said no.

Giovanni is descended from a long line of Italian royals, she told them. He was the Marchese de Monferrato.

He wasn’t, but my grandparents were persuaded, and the birth certificate was sent, and my parents married soon after. When they moved to Seattle, my grandparents found out that Giovanni was no marchese, but by then it was too late.

•••

I wondered, newly married, when I would tell my mother. I didn’t think I was making a mistake. I wanted to help Emir. I believed in his talent as a screenwriter, and that he deserved to stay in this country. But I wondered if this strange rebellion was in my blood, if deception had somehow become just as much a part of marriage as love. There was something pleasurable about the insistence, the necessity: I’m doing this no matter what. There will be hard times, new beginnings, other loves, stupid mistakes. Illnesses, travails you cannot foresee or imagine.

But this much I can promise: I am keeping you with me. Til death, or divorce, do us part.

Liza Monroy is the author of The Marriage Act (on sale now from Soft Skull Press) and the novel Mexican High. You can read more of her work on www.lizamonroy.com.