It’s All In Your Head: A Conversation About Being Sick Without a Diagnosis

by Jen Brea and Eva Hagberg

Jen Brea and Eva Hagberg met 15 years ago, in college. After graduating, Jen moved to China and worked as a journalist and then to Cambridge, Mass., where she started a PhD program in Government. Eva moved first to New York City to work as an architectural journalist, and then to Berkeley, where she got a master’s degree and then invented her own PhD program. Three years ago, Jen got sick — really (and for a long time, mysteriously) sick. A year and a half after that, Eva got sick. Really sick.

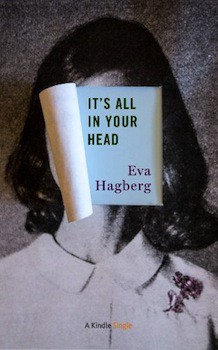

Eventually, she reached out to Jen. Turns out Jen was making a movie, Canary in a Coal Mine, which documented multiple peoples’ experiences with myalgic encephalomyelitis, her diagnosis. And then Eva wrote a memoir, It’s All In Your Head, about her experiences searching for — and failing to find — a diagnosis of her own. Canary in a Coal Mine ran a Kickstarter campaign earlier this year that raised over $200,000, while It’s All In Your Head was a bestselling Kindle Single and selected as one of Amazon’s Best Digital Singles of 2013. And still, Jen and Eva were both sick. Recently, they met up on the internet (one of the best ways for sick people to connect), to talk about what they have learned, how hard they’ve had to learn it, and making art in the time of illness.

EVA: OK, so: here we are! I think I want to start with asking a really basic question which is, how are you doing in this moment right now — where are you, and what has your day looked like?

JEN: Every day is different. I was doing great the last few days, and today I’m not. That’s sort of how it always goes. ME is a strange disease. You crash, you rest because you can’t do much of anything else, and then very slowly you start to climb out of the hole. Then suddenly, you feel like you have your powers back, so of course you use them. So today, I woke up and my heart rate is about 110 when I stand, which isn’t as bad as it gets, but it means I can’t even sit up in bed without stressing my heart. When you do what you love or feel called to do, you pay.

EVA: Let’s catch our readers up to how we got here — online, having a conversation about being sick.

JEN: We met in college, at Princeton. We’ve known each other for a long time through mutual friends, but were never very close. Then suddenly, this strange thing happens, and we feel like long lost family. Soul sisters. I’ve had that with other patients, too. I feel like I’ve joined a new tribe at the age of 30, and now those are my people. The dizzy people. It can be hard for folks who have not gone through something like this to understand. There are rites of passage we will all go through someday, and usually you do them with your cohort. Getting sick when you’re young is isolating.

When you first got sick, what story did you tell yourself about what was happening to you?

EVA: I was 25, living in NYC, feeling pretty invincible. I got dizzy, went to a doctor, and she gave me antibiotics, diagnosing an inner ear infection. And I got better, so I was like yay, that was funny but doctors are great! I had total faith in medicine. And then about a year after that happened, I got dizzy again — so I was like, OK, I just got another ear infection. Called my doctor, she gave me antibiotics, and… nothing. So I’ve either had a five-year ear infection or there’s something else going on. And I went through so many different stories. SO many. But I think I can break it into a few stages now:

1. This is a totally random physiological thing and medicine will work.

2. This is some emotional thing that has to do with sobriety — for about a year, I literally believed that my brain was making me feel like I had had a glass of wine at all times (which is how it felt to be dizzy) because I couldn’t handle being totally sober in the world.

3. This is anxiety.

4. This is not anxiety, this is something really bad, but we will figure out what it is (so I guess back to stage 1).

5. This is cancer and I’m going to die.

6. This is cancer and I’m not going to die.

And now I’m at:

7. This is probably NOT cancer and I’m not going to die, but I might be chronically ill/dizzy for the rest of my life, and how do I learn to accept that?

JEN: My first diagnosis was an inner ear infection!

EVA: WHOA! Twinsies!

JEN: It sounded like total bullshit at the time.

Not cancer is not a bad place to land. It’s strange, though. Somehow we know how to deal with cancer. Or at least, we think we know the story. As I’ve been working on this film, I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that we have been telling stories for thousands of years about living life, getting struck down by an illness, and then either dying or magically recovering. We don’t really have many stories about getting sick and never getting better.

EVA: We’ve talked about how our experiences, even if in a way they’re super-specific, are emotionally universal. Everyone gets knocked down and lives with uncertainty, etc.

JEN: Yes, everyone has or will get knocked down. This experience has been hard and specific, but at the same time, I think it’s revealed what has always been true about life. You get into a car accident and you think, “Wow, life is precious, life is fragile.” That was true the day before the wreck…we all live with that fragility. I just don’t think I realized that before.

EVA: Exactly. I’ve been noticing since getting the clear PET scan, I keep saying, “I’m not going to die this year!” And then I have to add on, “Probably!” Because I might still get hit by a car/have some flukey thing/whatever. So I realize that now that I got the clear PET scan I’m acting like I have a future again. But: do I really have any more assured of a future than I did the day before I got the voicemail from my Stanford oncologist telling me they didn’t see any tumors? No.

JEN: I’d love to talk a little bit about your experience with doctors. You did not start getting real medical attention until several years into your symptoms. Crazy chick syndrome?

EVA: Definitely. My doc in NYC basically gave up on a diagnosis, then I moved to Portland because I thought it was the stress of living in NYC, I basically ignored my symptoms, then tried again when I got to grad school and went on Celexa (an SSRI anti-anxiety med) for 1.5 years because a doctor talked to me for 10 minutes and said, “Oh, you’re dizzy because you’re anxious, and that’s totally common for grad students or people in high pressure environments.” And the Celexa totally numbed me out so I didn’t care that I was dizzy all the time. But yeah, I went pretty far down a rabbit hole of thinking, “this is just me being unsocialized or anxious or something I can’t really explain.” I mean, the month that I ended up in the hospital I was working through this thing with my father, who hadn’t been in my life for a really long time as a kid and I was being told that I was going through childhood trauma, and that this is why I was having night sweats and forgot how to make sentences. I couldn’t get out of bed in the morning, I had zero appetite, and I had excruciating thirst, but I was unable to actually drink water and I slept 14 hours a day.

JEN: I was also told that my symptoms were grad school-related. The doctors I was seeing at the health clinic kept hinting my troubles might be psychiatric in nature. My neurologist told me that all of my symptoms (including the complete immune breakdown of flu from hell, sore throat, sinus infection in a matter of weeks) were psychosomatic — caused by some psychological trauma that I might not even be able to recall. Conversion disorder, in other words.

Also, why do so many doctors still inadvertently learn and quote Freud? In what other realm do we still consider 19th century medicine as authority?

EVA: Oh, the Freud. I mean, it’s 2013, you and I are both PhD students at good schools, and we are basically being diagnosed with hysteria. I’m amazed they didn’t just do hysterectomies on us.

Also, why do so many doctors still inadvertently learn and quote Freud? In what other realm do we still consider 19th century medicine as authority?

But did you ever believe them? Because I’m so ashamed of this but I totally had phases of believing absolutely that I was just like really weirdly depressed maybe? I write about this in my book, but the resident at the hospital I was admitted to literally diagnosed me with depression — the day before an MRI showed a bleed/series of masses in my brain.

JEN: Yes, I did believe them. I wanted to prove to myself that I was a rational, scientific sort of person who would not reject any hypothesis out of hand, even one that might mean I was crazy. So, I walked home from the clinic that day, meditating on the psychosomatic pain in my legs and the psychosomatic dizziness in my head. When I got home, I collapsed. My brain and my spinal cord were burning and I could not walk. I was essentially bedridden for the next five months. Through my wedding.

If I had listened to my body instead of my neurologist and my need to prove that I wasn’t an irrational woman, I don’t think I would be as ill as I am now. I was on the edge of a cliff that day and I jumped off it.

EVA: I did find a lot of strength to push on by watching you keep pursuing a diagnosis — I just kept thinking, OK, if Jen can do this then I can do this. And again, that’s a general life thing. We watch other people do stuff that we never imagined we could do, and then we can do it.

JEN: I think I had always been used to being believed and having a certain amount of authority with respect to my ideas and certainly my own experience. It probably has to do with going to a “good” school, like you said. I am stubborn, opinionated, and confident. I’d never been condescended to before, or treated like a little girl, or not been engaged with as a partner, not to mention somehow made to feel like I was an unreliable witness. If this is happening to folks with our education and privilege, I just can’t imagine what it’s like for folks with less privilege.

EVA: Exactly. I had my mom basically running interference all the time, and she’s an extremely respected professor of philosophy and really knows how to write formal letters and be very calm and informed, and my male doctors were still responding to both of us as if we were just exaggerating. One of them literally wrote, “There is nothing dangerous going on here.” And this was like two days after I almost went into a coma because my sodium got so low.

JEN: I know. I know. I know. I feel like my film is on some level my attempt to finally speak up for myself.

EVA: So right, you’re making a feature-length film, Canary in a Coal Mine, and I’ve seen a couple of trailers and clips and I usually cry. It’s gorgeous, what I’ve seen so far. And it seems to me that some of it is absolutely polemical and really engaged in giving voice to this whole community, and that’s so important. And then there’s the part of it is that is like art-making, and I’m curious about your relationship to your life and your work, and if that changed.

I found that writing my Single was profoundly therapeutic but because it allowed me to just work. For months, it felt like my only job was going to doctors. And suddenly I had this project, and I had to take some fact of my life and figure out the best way to narrate it — should this be direct dialogue? Should it be a long sentence or a short sentence? In what order should this go And then my friend Jamison Wiggins — who I talk about in my piece quite a bit — started making movies about my experiences going to the doctor, most recently this piece he’s calling How to Magnetically Resonate, which turned out to be this (I think beautiful) meditation on friendship and solitude and just getting through it (i.e., life) together. And the experience of being able to part of his art-making — to be able to have my experience used for someone else’s work — was also tremendous for me. So I’m really curious — what does making the film do for you, on a day-to-day basis?

JEN: I grew up in the Catholic church, and my favorite homily was about what our calling is in life. It was this idea that we are all called by God to walk a certain path in the service of His plan and in the service others. When we are on that path, we’ll know it. Now, it’s been a loooong time since I’ve been to church, and I would never say that “this happened to me for a reason, it is good.” But what I do know is that if and when my life falls apart, I need to take that (random or not) and make it have meaning. So making this film makes me feel less like a victim. It’s been incredible being a part of the ME community and being so embraced and helped by other patients, and in turn doing my part to help them.

I also think that as a woman who before getting sick was really ambitious and driven to do work that mattered, a significant part of my identity I derive from my intellectual and creative output. So when that work that I was doing — work that required that I show up some place and be a part of society — was no longer possible, I became a patient. And when you can’t give to others, you stop feeling like a person. So, even though I can’t fry an egg, I can make a film. And that means that I can be Jen again. I can do work that matters, I can try to give to others, and I can take all of this stuff that’s inside of me-the beauty, the pain, the sadness, the gratitude, and make something of it. Because if I just let it all fester, I won’t survive this.

So when that work that I was doing — work that required that I show up some place and be a part of society — was no longer possible, I became a patient. And when you can’t give to others, you stop feeling like a person.

EVA: There are two main things here I want to pick up on: One is acknowledging that these disasters didn’t happen to us for a reason. My life has changed enormously (in many ways, for the better) since getting sick. I have had this massive shift in perspective, I feel gratitude as a tangible thing, and I’ve found the love of my life. But it is so important not to fall into this trap of thinking, “Oh, I got all this stuff so that all happened for a reason.” It is a fluky, random, senseless, nonsensical thing that you got sick and that I got sick.

But then I feel like we can let that fester or we can try and make something of it. And I absolutely share your experience of feeling like I couldn’t give anything to anyone when I was really in it — pre- and post-brain-surgery, I couldn’t cook, entertain, have people over, play cards, go on hikes, whatever. But what I could do was be really honest, and kind of send missives back from this cliff edge I felt like I was on. And your list of things inside — beauty, pain, sadness, gratitude — I mean, we all carry those with us. But I think we’re conditioned to always equalize. I’ve found that I’m able to sit with other peoples’ pain in a way that I never could before. But also I want to say that as well as changing for the better there’s a lot of stuff that has changed for the worse — I want to be very careful not to act like it’s a gift, because it is not. Being sick blows.

JEN: I wish I could have gotten the gift without the bloody mess, but I don’t think life works that way. Maybe with the film, I can give that to other (healthy) people.

•••

This is where we took a break from our chat, and it took a few weeks to find time in which we could both use our brains again. During those weeks, Eva went to an electrophysiologist, who discovered a problem with her heart: a syndrome called Wolff-Parkinson-White, which requires minimally-invasive surgery to correct it. Jen raised $200,000 on Kickstarter for her movie.

EVA: So you were about to launch the Kickstarter campaign when we did the first run at this, and now you’ve just raised over $200K. Congratulation! How does that feel?

JEN: It’s surreal. This is such an underdog of an illness that on the one hand, you get used to not being paid attention to, not taken seriously. And yet there are millions of people who are severely ill and being mistreated. So on the one hand, I am still in shock; I never could have dreamt this. On the other, it makes complete sense. There is a huge, unmet demand for stories like this one.

But also, I’ve been caught in a post-Kickstarter funk.

EVA: That’s how I felt after my book got published. It sold like crazy when it was first out, I was experiencing this new kind of success, and then I still had to go get IV saline twice a week. And I was like “WTF. I thought we were done? The story is finished?”

JEN: It was that “magical thinking” you wrote about on your Facebook page. The film, the campaign were all really important moments of emotional healing. But emotional healing is not the same thing as physical healing, and so even after the campaign is done, and even, in a few years, once the film has been released, I may still be sick. And no amount of art is going to make me transcend my body.

Eva: YES. Exactly. There’s so much rhetoric around the mind/body connection, like I’m already having imaginary arguments with people about the next problem being my heart. You know, everyone was like “Oh, of course you have a brain

thing because you’re so cerebral” and now it’s like, “Ahhhhh yes, your HEART needs healing.” And I’m like, “go fuck yourself. I have Wolff-Parkinson-White, this is nothing to do with heart healing feelings.”

Haha, clearly I have some unresolved anger about my situation.

JEN: Ha! I know, right? What if it turns out to be your spleen?

What do you hope for for the future? Do you still expect to get 100 percent better?

EVA: Nope. I expect at this point that I don’t have cancer but that I’ll be dizzy and kinda tired forever. This heart ablation might change that, it might not. But instead of looking backwards and wishing I felt like I used to feel, I have many more moments of just accepting that I basically never feel hungry, I’m always a little nauseated, and I’m probably going to have periods of pretty intense dizziness, forever. So my concerns are more practical and day-to-day — how can I conserve energy and plan realistically? Hilariously, I’m debating right now if I should go to yoga class — I’m exhausted and have a big speaking commitment tonight — and I’m still like, I SHOULD GO I’M FAT AND LAZY. (I am neither fat nor lazy.) So it’s like paying attention to my body day to day. At this point I will be very upset if I do have a brain tumor, but also I feel like I can handle it… well, I should be careful what I say. Not anything. But I can handle what I have in front of me, which right now is a few more MRIs and a cardiology appointment. But this idea of returning to a glorious perfectly healthy state is gone. Huh. Just realized that as I wrote this out. What about you?

JEN: When I think about tomorrow or later this week I can handle it, psychologically. But when I think five, 10 years, it’s just much too overwhelming! So I don’t think about the future. I think it’s likely I will never have my body back, but I know that I can improve, and so I fight for that everyday. Still, some days I wake up and I despair. And some days I wake up and I am perfectly content. Which, I suppose, means that, if anything, I am still human.

Do you want to try to end this on a happy note, though? Or if not happy, dark, and hilarious?

EVA: Yes. Dark and hilarious.

I don’t know that happy notes work for us anymore. But I think dark, hilarious, weird jokes are important. Here’s what my mom said when we realized the heart doctor I was seeing specializes in “sudden death.” She immediately was like “How does he hold on to a patient base???”

LOL, mom.

JEN: Nice. So you have a structural heart defect?

EVA: I have Wolff-Parkinson-White, an extra electrical conduit in my heart.

JEN: Oh my gosh! I googled that once. I feel so honored to know someone with such a rare defect.

EVA: 0.15 percent of the population, baby. I’m special.

JEN: That beats my 0.3 percent. I’m a little jealous, because I’m just competitive that way. But honestly, I’d like to come in second for once in the “how sick and weird are you?” race.

EVA: Get in line. Behind me. I got this one.

Photo via khaz/flickr.

Eva Hagberg is the author of It’s All In Your Head. She’s on Twitter @evahagberg. Jen Brea is the director of Canary In A Coal Mine. She’s on Twitter @jenbrea.