Roe v. Wade at 40: Part II of an International Roundtable

by Michelle Kahn and Rachael Hill

This is the second installment in a two-part roundtable about the effects of Roe v. Wade as the case’s 40-year anniversary comes to a close. Read Part I here.

Motherhood and Feminism in the Wake of Nazi Biopolitics: The Struggle for Reproductive Freedom in Germany

by Michelle Kahn

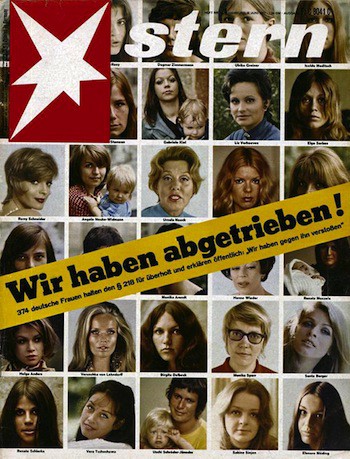

“We had abortions!” With those three words, screaming off the cover of the June 6, 1971 issue of Stern magazine, 374 West German women not only spilled a very taboo, still illegal secret but also expressed frustration with the inaction and relative timidity of their feminist movement. “German women don’t burn bras and wedding dresses, don’t storm beauty contests and anti-emancipation newsrooms, don’t call for the abolition of marriage, and don’t compose manifestos for the destruction of men,” radicals within the movement complained. Compared to their sisters in the U.S., West German feminists lacked “fury.”

Part of the problem lay in the peculiar situation Germans confronted during the Cold War. With their country physically and ideologically divided, self-definition against the East German “Other” permeated the rhetoric and reality of West German feminism. In a postwar climate dominated by conservatives well into the early 1960s, leftists found that maintaining legitimacy required careful demarcation of their beliefs from those of their enemies across the Iron Curtain. That meant shying away from East German “gender-leveling,” an artifice of full equality of the sexes with roots in Soviet-style socialism. To quote Elisabeth Selbert, one of only four women present at the drafting of the 1949 West German constitution who was instrumental in pushing through a clause on women’s rights, “I have never been a women’s righter, and I will never be one.”

Another issue undergirding contemporary understandings of reproductive freedom in the German case is the legacy of National Socialism and war. The Nazis’ 1933 seizure of power quashed 1920s sex reformers’ efforts to liberalize the Penal Code’s Paragraph 218, which, since German unification in 1871, had criminalized abortion and the establishment of birth control clinics and counseling centers. Amid anxiety about declining birth rates, and struggling to secure the future demographic stability of the German Volk, the Nazis appropriated an intensified version of what one historian has called a pre-existing “motherhood-eugenics consensus” — a belief that “motherhood was a natural and desirable instinct in all women, only needing to be properly encouraged, released, and regulated, and which understood the bearing of healthy offspring as a crucial social task.”

For the vast majority of married German women, Nazi pronatalist policies involved a certain degree of choice, as well as incentives — from social welfare benefits, like marriage loans, to medals (bronze for five children, silver for six children, and gold for seven children). But the Nazis were not just interested in quantity. When it came to quality, the “Aryan” racial genetic fitness of a parent, the regime exercised a much darker and restrictive biopolitics. The 1933 Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring justified the sterilization of up to 400,000 men and women throughout the Third Reich. On the other extreme were institutions like the state-sponsored maternity homes of the radical and controversial Lebensborn program, alleged (despite no scholarly evidence) to have carried out the compulsory “selective breeding” of young, unwed “Aryan” women and dashing SS men.

Yet, in a way, the experience of Nazism and the Second World War also ushered in a short-lived liberalization of abortion law and practice in the immediate postwar period of Allied occupation, 1945–1949. But this was no victory, as it came out of a great cost. In the postwar East, the mass rape of up to two million German women by the invading Soviet “liberators” in May 1945 added a traumatic experiential layer to the abortion debate. Responding to the crisis, physicians ad hoc suspended Paragraph 218 and began terminating the pregnancies of violated women. In 1947, officials in the Soviet Zone decriminalized abortion altogether, only to recriminalize it in 1950, a year after the formal transition from occupation to East German self-governance. It was not until 1972 that East Germans, following trends on their side of the Iron Curtain, relegalized first-trimester abortions. The next year, a remarkable 38 percent of all pregnancies were terminated. Certainly, women were exercising their newfound right to control their fertility. But the statistic also testified to their lack of reproductive freedom in another sense: amid the economic crisis and shortages that plagued the socialist state, other contraceptive measures were hard to access.

By contrast, by 1971, when Stern magazine published its iconic “We have aborted!” cover, West German sex reformers could lay claim to widespread use of the Pill and the world’s first above ground, brick-and-mortar erotica shop. But abortion reform lagged a year behind the East. Marginalized in the 1968 New Left student movement and galvanized by developments in Western Europe and the U.S., West German feminists finally rallied together for reform of Paragraph 218. In 1973, they succeeded — to a point. Abortions were still deemed unlawful but were permitted conditionally, only after a mandatory counseling session and certification of the procedure’s necessity by not one, but two, physicians.

Not surprisingly, the East and West German models came to a head in 1990. With the fall of the Iron Curtain and German reunification, the pressures of reconciling two vastly different political, ideological, and legal systems extended into the realm of reproductive rights. It took five years of political and constitutional battling for lawmakers and jurists to decide on a compromise solution: first-trimester abortion after mandatory counseling, with exceptions for situations of rape and the mother’s physical or mental endangerment.

Today, despite this relatively liberal law, Germany boasts one of the world’s lowest abortion rates — about a third of the U.S. rate — reflecting, as some have suggested, the government’s remarkable social welfare benefits available to women who become pregnant: among them, fourteen weeks paid maternity leave and financial allowances for each child. Both of these policies, it is worth pointing out, can be traced to the family-oriented pronatalism of the West German 1950s, itself a tempered down legacy of the pre- and Nazi-era “motherhood-eugenics consensus.”

While Germans have certainly recovered from the severe restrictions on reproductive freedom of the Third Reich, one major issue requires more attention: public discourse surrounding the fertility of immigrant women. Just this September, the youth wing of Germany’s far-right National Democratic Party ordered and distributed condoms labeled, “For foreigners and certain Germans.” An accompanying letter assailed the “unchecked immigration and the resulting population change in our country,” which is leading to “demographic catastrophe.” Eerily reminiscent of the National Socialist past, this xenophobic rhetoric is not new; it just has a new target. In the struggle for securing and maintaining reproductive freedom throughout the world, it is something worth keeping an eye on.

Michelle Kahn is a PhD student in Modern European History at Stanford University.

Women’s Economic Empowerment and Reproductive Freedom in Africa

by Rachael Hill

An estimated five million illegal unsafe abortions are performed in Africa each year — with 25 percent performed on adolescent girls. As many as 36,000 of these women die from the procedure, while millions more suffer illness or disability. Nearly a quarter of all maternal deaths in Africa are the result of illegal unsafe abortions. These alarming statistics have catalyzed various forms of activism around the issue of abortion rights on the continent. However, the problem of unsafe abortion can only be adequately addressed by a holistic approach to sexual and reproductive health that goes beyond discretely addressing women’s rights to a safe abortion and contraception to include women’s rights to economic resources.

African states have a number of laws inherited from the colonial era — laws that almost invariably enhanced male authority at the expense of women’s. Colonial laws governing property rights, marriage, child custody as well as reproductive health reflected colonial regimes’ preferences for patriarchal structures and rigidly defined gender roles. Under colonialism, abortion was a serious crime; generally, saving the life of a pregnant woman was the only permitted exception. Many of the laws governing abortion in Africa today were originally imposed by European powers that have long since done away with restrictive abortion laws in their home countries.

However, highly restrictive abortion laws alone do not necessarily constitute the biggest barrier for women seeking to safely end an unwanted pregnancy. While the majority of African women of reproductive age continue to live under severely restrictive laws, South Africa and Ethiopia are two nations that have significantly liberalized abortion laws. South Africa’s post-apartheid legislature passed the first law in sub-Saharan Africa legalizing abortion without restriction in the first trimester. Studies suggest that legalizing abortion had little impact on the rate of unsafe, illegal abortions in South Africa. The long waits, high costs and shaming of abortion patients in the public health sector cause women to continue to seek out illegal, unsafe alternatives. In Ethiopia, seven years after abortion law was liberalized, only a quarter of all abortions occur in safe and legal settings for many of the same reasons. Clearly, liberalizing abortion law is not the most meaningfully way to promote women’s reproductive freedom.

Yet many international women’s organizations continue to pour an enormous amount of energy and resources into defending abortion rights and promoting contraception. Unfortunately, many forge alliances with population control advocates who prioritize limiting births over women’s general health while callously dismissing resistance to “family planning” as evidence of Africa’s cultural backwardness.

Recently, The Gates Foundation partnered with the pharmaceutical company Pfizer, the maker of the injectable birth control Depo-Provera, in a mission to rescue African women from the burdens of childbearing. Melinda Gates describes this project as a crusade in the name of women’s reproductive health in Africa despite a decade of research suggesting that Depo-Provera significantly increases the likelihood of HIV/AIDS infections and breast cancer. Women using the shot have also shown to have a suppressed immunity and a decreased ability to absorb nutrients from food. It doesn’t take a health expert to understand how this is could be particularly problematic for low-income women who are already at risk of being nutrient deficient and in poor health. Furthermore, when providers are incentivized to promote the use of Depo-Provera, women looking for birth control in African clinics are rarely provided with a range of choices or given all of the information on potential side effects. If contraceptives are to be instruments that allow women to make choices about their own fertility, then women have a right to access knowledge about the risks/benefits of any given method as well as information about alternatives. Family planning methods driven by political concerns about population control or providing pharmaceutical companies with lucrative business are not steps towards greater reproductive freedom for women and ultimately play into the hands of critics in countries like Uganda who hurl blanket accusations of “neocolonialism” at all women’s rights groups.

There are a number of historical reasons for people to be skeptical of external efforts to limit women’s fertility. In South Africa, the apartheid regime once used forced birth control methods on women as a political instrument to control the growth of the country’s African population. Women on white-run commercial farms in Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) were often coerced into accepting Depo-Provera as a condition of employment. The forced and coerced sterilization of HIV positive women in various parts of Africa is a contemporary reality.

However, contraception and abortion are not new in Africa. Married women and mothers in many African societies historically practiced contraception. Prolonged breastfeeding and post-partum abstinence enabled women to appropriately space births and limit the amount of children they had. Also common throughout much of Africa was women’s use of anti-fertility and abortifacient herbs to regulate their own reproductive capacities. In short, it was not uncommon in much of Africa for women to exercise considerable physical autonomy; the fact that practices that limit this power have come to be known as “cultural” and “traditional” is misleading. In fact it was when women’s reproductive capacities became institutionalized as the private property of their fathers and husbands that women became less empowered to make decisions about a wide range of issues — including sexual and reproductive health.

Today, women in Africa represent more than half of the total population, contribute approximately 75 percent of the agricultural work, and produce 60–80 percent of the food. Yet they earn only 10 percent of African incomes and own just one percent of the continent’s assets. The notion that poor, sub-Saharan African women are victims of their own fertility — as opposed to victims of an inequitable economic order — contributes to a troubling conflation of externally imposed fertility limits with “voluntary family planning.” It makes pregnancy the enemy of women’s reproductive freedom, not poverty exacerbated by gender discrimination. When women lack financial security they are forced to choose a sexual partner or marriage out of economic necessity, effectively surrendering control of their reproductive capacities. This makes women vulnerable to early marriage, sexual violence and exploitation — all of which increase the likelihood of unwanted pregnancy. Hence, the only successful path toward greater sexual and reproductive rights for women in Africa is one that is committed to a broader agenda of women’s economic empowerment.

Rachael Hill is a PhD candidate in African History at Stanford University.

Photo via imlsdcc/flickr.

Previously: Part I (USA & China)