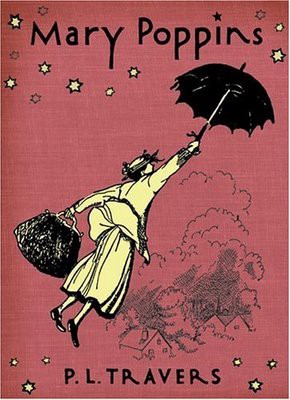

In Praise of the Real Mary Poppins

by Mia Warren

I met the real Mary Poppins one warm afternoon circa 1999, in my hometown, in the public library. She was sitting on the musty shelves of the children’s section. Quickly enthralled, I immersed myself in the Banks children’s adventures for the rest of the summer.

This character had a tone far removed from the sweet, lilting soprano of Julie Andrews, who — like many other children — I had encountered in the 1964 Disney film. This Mary Poppins was the fearsome creation of author Pamela (better known as “P.L.”) Travers, and she was never sprightly or sentimental. In fact, most often, she was sort of a bitch, and I loved this about her.

Walt Disney, however, did not. As the new (Disney) movie Saving Mr. Banks depicts, Mr. Disney’s attempt to adapt P.L. Travers’ creation for the silver screen became a prolonged battle: a fight of ideological difference between a man who wanted a spoonful of sugar and a woman who knew that her character, if she didn’t like you, would happily switch that spoonful out with salt.

Because, for someone given the position of surrogate mother, the original Mary Poppins is almost never nurturing. Her main childcare techniques include emotional bullying, withholding affection, and brute intimidation. The exchanges between the Banks kids and their nanny are rife with negativity:

By now they had come to the end of the High Street. But still Mary Poppins did not stop. The children looked at each other and sighed. There were no more shops. Where could she be going?

“Oh, dear, Mary Poppins, my legs are breaking!” said Michael, limping pathetically.

“Can’t we go home now, Mary Poppins? My shoes are worn out!” complained Jane.

And the Twins began to whimper and whine like a couple of fretful puppies.

Mary Poppins regarded them all with disgust. “A set of Jellyfish — that’s what you are! You haven’t a backbone between you!” And popping the shopping-list into her bag, she gave a quick contemptuous sniff and hurried round the corner.

Mary Poppins Opens the Door, 1943

She is contradictory in more than just the motherhood realm. While she’s a paragon of feminine grace and a near-perfect physical specimen (and ostensibly, an object of desire for many men), romantic relationships don’t seem to interest her in the slightest. Bert the Matchman is constantly doting; MP remains staunchly unattached. Her family connections are similarly sparse. The few eccentric relatives we encounter — from the floating Uncle Albert Wigg to the Man in the Moon — hail from other worlds and rarely make reappearances.

So, while she is positioned as an icon of the domestic sphere, Mary Poppins — the real one — possesses few of the personality traits (kindness, gentleness, humility, suggestibility, attachment) that traditionally have been associated with ideal womanhood in Western societies. Yet despite of this, and perhaps because of this, her performance of motherhood reigns supreme. Despite what could be construed as a severe lack of empathy (and minus the implied innate goodness, possible sociopathy), MP channels efficiency like no one else. When she enters the chaotic Banks household, order and structure win the day:

It seemed to [the children] no more than a minute before they had drunk their milk and eaten their cocoanut cakes and were in and out of the bath. As usual, everything that Mary Poppins did had the speed of electricity. Hooks and eyes rushed apart, buttons darted eagerly out of their holes, sponge and soap ran up and down like lightning, and towels dried with one rub.

Mary Poppins Comes Back, 1935

The original Mrs. Banks is a self-absorbed hypochondriac who occupies a tertiary role in her children’s lives. When she fails spectacularly in her maternal role, Mary Poppins steps in, and the Banks family quickly learns to defer to MP’s expertise on most matters. That a single, childless lady claims such immediate authority is an interesting paradox at a time when abiding Victorian ideals championed marriage and motherhood as ultimate confirmation of a woman’s worth. Yet Mary Poppins’ marital status is rarely remarked upon by other adults in the books. The Bankses, though at times resentful of their employee’s superciliousness, acknowledge that her presence makes their children’s lives — and by default, their lives — easier.

Mary Poppins’ vanity is an integral part of her personality. Unapologetically, she spends many moments scrutinizing her flawless appearance:

“Just look at you!” said Mary Poppins to herself, particularly noticing how nice her new gloves with the fur tops looked. They were the first pair she had ever had, and she thought she would never grow tired of looking at them in the shop windows with her hands in them. And having examined the reflection of the gloves she went carefully over her whole person — coat, hat, scarf, and shoes, with herself inside — and she thought that, on the whole, she had never seen anybody looking so smart and distinguished.

Mary Poppins, 1934

In Myth, Symbol, and Meaning in Mary Poppins, Giorgia Grilli compares Mary Poppins to the Victorian dandy, whose antisocial tendencies and open revulsion with others “established a distance between himself and the somewhat distasteful world of those surrounding him.” Like the dandy, who protests a “ready-made world of predictability and control,” MP often distinguishes herself from the Banks family and other mortals (more than once, it is implied that she is immortal). Grilli goes on to argue that Mary Poppins’ pristine outward presentation is “no mere aesthetic attitude” but rather a “form of ceremony” intended to “subvert…[the] small-mindedness” of those living in the conventional world.

Energetic, smart, presentable, and sensible, Mary Poppins contrasts starkly with the other women of the house, from the infirm and vacuous Mrs. Banks to the sloppy and silly housemaid Ellen. What’s more, she knows she’s better than everyone else — and she often revels in her superiority. Yet perhaps, as Grilli suggests, the original MP’s narcissism marks her rejection of stringent societal norms. As a childless, unmarried woman living in (what is probably) Edwardian England, Mary Poppins derives her inherent worth from twisting traditional feminine norms. She is beautiful and a diligent worker, but she also lives free from the constraints of life as a wife or mother. As far as we can tell, MP operates on her own and is solely responsible for her finances. She doesn’t even depend on the Banks family: technically, she’s a part-time employee who departs from the household at the close of every book (where she goes for the rest of the year remains a mystery). True, these frequent hiatuses could very well be just a sequel-generating narrative device, but I prefer to think it was P.L. Travers giving her character a woman’s due: a sustained financial independence achieved within the strictures of reality, but fiercely on her own terms.

(It’s worth noting, too, the minor revolutions that Travers herself represented: she was bisexual, she adopted a child at age 40 based on the advice of her astrologer, and she spent years at a time in Japan, studying mysticism, or on Native American reservations, studying folklore. In a 1994 interview with the New York Times, the reporter asks Travers, “Have you had enough of me?” and Travers “promptly” replies yes.)

In Hollywood, we’ve seen countless iterations of female characters who suffer from some kind of deficiency — whether physical, social, or intellectual — supposedly to make them more digestible for audiences. Some heroines trip constantly, as Mindy Kaling pointed out in the New Yorker. Others struggle to balance boyfriends and bosses. As a strong female character, Mary Poppins is one of the original Bitches Who Get Stuff Done. She would never fall on her face in the name of being appealingly imperfect. Plus, as readers, we know she’s not perfect. Her belief that she is perfect only emphasizes her imperfection. And the key to creating a strong female character lies in just that: neither glossing a woman to perfection nor imbuing her with stereotypical weaknesses. At her best, Mary Poppins is a treasure of domestic bliss. At her worst, she’s an egotistical oppressor. But she’s never boring or simplistic.

In the Saving Mr. Banks trailer, stubborn P.L. Travers (played by Emma Thompson) protests every alteration Mr. Disney (Tom Hanks) tries to impose. To prepare for this role, Thompson listened to Travers’ tapes of long, agonizing meetings with members of Disney’s creative team. Though Travers initially pushed hard to preserve the Mary Poppins she had created, she eventually “gave up at some point,” too cash-strapped to fight any longer.

I can’t help but attach a certain irony to Travers’ struggles with Disney. While Mary Poppins stayed relentlessly true to her values, her creator was forced to compromise to survive. I can only imagine MP disapproving from afar, scornful and smirking.

Mia is researching the Japanese Peruvian community in Lima, Peru. Check her out at Sarcasmia, Twitter, and Tumblr.