How the Nutcracker Wrecked My Christmas

by Patrice Hutton

I.

The year that four of us were a family in the Nutcracker, night after night pretending to have Christmas on stage, we stopped putting the Christmas tree up. We rehearsed instead of decorating. Then my mom had my little brother and retired from the Nutcracker for a second time in her life. The Christmas tree went back up, but this time, its branches drooped with pink. We’d retired the normal Christmas ornaments and hung every last ornament that one of us had received as a Nutcracker gift. Ballerinas and pointe shoes and so many Nutcrackers and mice and soldiers and Claras: characters and shoes enough for fifteen productions danced on the tree.

II.

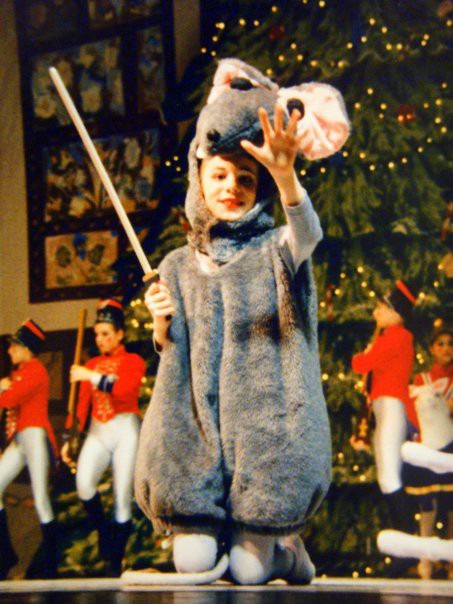

By the fourth Nutcracker in three days, my little brother lay in the aisle, his cheek pressed against the cold concrete; by his 102nd production, the Nutcracker only induced sleep. Meanwhile, my parents hid in the third balcony, taking pictures. Ushers were the enemy, filling up the SD card was the goal, and someday, when their daughters were no longer in the Nutcracker, they would spend their retirement watching a video of every single performance, all twenty years (and counting) that their three girls had been onstage.

III.

There used to be a sacred period in December, more glorious than Christmas itself. It spanned the five days before the holiday, when we milled about the dusty, grown-up cow town we grew up in. Magic happened: we lit black powder off the blades of machetes, ran screaming across fields avoiding wolves that went extinct in 1905, and fell asleep huddled in front of blazing fireplaces. One of the things I’ve most dreaded about growing up is losing these days, and now that my sister is a professional ballerina, they’re gone. Now my parents force me to sit through four Nutcrackers in California, beaches and sunsets strictly prohibited. So while I listen to the celesta of the Sugar Plum’s dance — once, twice, thrice, there’s not even a word for the fourth viewing — a stretch of scared prairie days passes without me.

IV.

The Nutcracker, my once-great love. In August, we’d audition. In September, we’d rehearse. In December, we’d perform. January through June felt empty, but July was better, because you’d start your pre-audition stretching routine. The month that JFK, Jr. died, I sat in center splits and read every news magazine about his death, thinking about how cute he’d been and how good my splits would be by the time auditions came around.

One December, after the Nutcracker was over, I wanted more, so I sat in my closet and wrote a sequel for the ballet. On a sheet of notebook paper, I detailed E.T.A. Hoffman’s neglected follow-through, and tried to raise all the stakes: a victorious battle for the mice, a blizzard instead of an enchanted snow forest, and a Land of Rotted Sweets, from which Clara had to escape.

And then every Christmas Eve I waited for Hoffman’s tale to come true. Surely, when I was thirteen, Clara’s age, I’d at least dream a relevant dream and for a few minutes of slumber believe that it was me who’d been whisked away to the Land of the Sweets with a darling Nutcracker prince. One year I was given a Nutcracker on Christmas Eve. I left the wooden man in the living room, just like Clara had done, and drifted to sleep expectantly. Instead I just dreamed my plane was crashing.

V.

Sausage, politics, and ballets: you don’t want to know how they’re made. Autumn is for directors screaming and stress fractures and learning how to draw fake eyebrows on your forehead. Then comes the show. Clara will barf on stage (gracefully, behind the couch), and the petite heroine will be switched mid-production: blonde for the party, brunette for the Land of the Sweets. My sister and I will fight on stage, dressed up as German children from the 1880s, me the unruly brother (suspenders and a curly wig), trying to rip a doll from her arms. We’ll get compliments for our acting and not speak for two days. The waltz dressing room will get reprimanded for decorating with mullet pictures, having offended the mullet-bearing custodian. Mothers will inquire backstage: are the homeless who squat in the rafters stealing eye shadow? Vomit will be left on stage and a mouse will slip, spraining her ankle. Mother Ginger will collapse, unable to rise on his stilted feet, trapping the Ginger Cookies beneath the skirt. By then a full blown flu pandemic will wipe the cast, and whoever’s not barfing will be dancing, no matter the role, no matter the knowledge of the choreography. Christmas will pass, and you’ll either not notice or still be barfing.

VI.

And then, one December the Nutcracker didn’t come. That year I played the role of a college student, writing papers in the library, wearing sweat pants, 1,200 miles away from the stage. By the time I got home for Christmas, I hardly recognized the holiday. It smelled different: poinsettias, cinnamon, a fresh snow. I lay in bed that Christmas Eve, wondering if I’d ever again smell the lovely mixture of sweaty feet, hairspray, rosin, eyelash glue — all that which, for a decade, had been Christmas.

Patrice Hutton is the director of Writers in Baltimore Schools. She’s currently a graduate student in writing at Johns Hopkins University. Her fiction appears in Mount Hope Magazine, Prime Number Magazine, and Outside In Literary & Travel Magazine.