Great Escapes from Women’s Prisons: A Brief History

by Jackie Strawbridge

Last week, I got sucked into a Wikipedia-wormhole on the subject of History’s great prison breaks. This led to some interesting reads, but turned up little to nothing on female escapees. It’s time we give some credit where it’s due.

SAMANTHA LOPEZ

The most screenplay-ready escape story is that of Samantha Lopez, who was whisked out of a California Federal Correctional Institution in November 1986 by her husband in a hijacked helicopter. The Helicopter Escape, it turns out, is a relatively common strategy among prison breakers, both male and female. (Wikipedia has a whole article on the subject.) It works as such: your accomplice steals a helicopter, dives it into the prison yard, scoops you up, and flies out before the guards have finished lacing up their shoes. But Samantha Lopez’s was not any regular helicopter prison break. It was a helicopter prison break of love.

Samantha Lopez met Ronald McIntosh in the prison business office, where they both worked as convicts. The couple first began dabbling in insubordination together by sneaking a kiss when the guards had their heads turned. McIntosh proposed within a year, but was soon afterwards transferred out of the prison; he left Lopez with the seemingly heart-wrenching request that she spend the next five afternoons sitting in the recreation yard, thinking of him. On day five, McIntosh appeared from above.

He had chartered the helicopter by posing as a property developer. Once in the air, he pulled a gun on the pilot; having flown helicopters in Vietnam, he was able to take control and guide it to the prison. He touched down on the prison yard for no more than 10 seconds, enough time to scoop Lopez up while her fellow inmates screamed and cheered. They ditched the helicopter a few miles away and headed to an apartment that McIntosh had rented in Sacramento.

Ultimately, it wasn’t any flaw in their escape plan that doomed them; it was their impatient love, suddenly unchaperoned and unrestrained: they used a bank account that the police were monitoring, and were nabbed at the mall on their way to pick up wedding rings.

If any of you work for the Lifetime Network, here’s some real-life imagery you would get to exploit in the made-for-TV-movie Hot and Heavy and Helicopters: The Samantha Lopez Story (…or whatever title you come up with. Honestly, it’s sort of incredible that this doesn’t already exist, anyway.):

• A prison-yard full of women celebrating Lopez’s escape by waving their shirts and throwing napkins at the receding helicopter;

• Lopez and McIntosh leaning out of separate police cars after their recapture, being driven in opposite directions, calling out, “I love you!”

• Lopez identifying McIntosh, in a sentence hearing, as “the man that I know and that I love deeply.”

• Their courthouse marriage in matching prison uniforms.

THE NIANTIC FIVE

A prison break doesn’t need to be sensational to be great, though, as proved by five women at the Niantic Correctional Institution in Connecticut in 1984. These convicts pulled off the prison’s first maximum-security break in 10 years, and its single largest break-out of the time, simply by pushing a screen off a window, squeezing through the gaps between the window bars, and strolling off the grounds.

To me, slipping out of a prison window like some kind of Zen Houdini is more incredible than an audacious helicopter escape. The window bar gaps at Niantic Correctional were seven-and-thee-quarters inches, a little less than the length of a drinking straw, and there was no evidence of tampering other than the removed screen. The escape was made easier in that Niantic Correctional Institution is “open-campus,” which means it’s not walled or fenced in (not that walled perimeters pose much of an obstacle for any of the other escapees covered here), and a Niantic Correctional spokeswoman stated vaguely that guards “were not in the immediate area, if any were there.”

I grew up in Connecticut, and maybe it’s just because I’m hyperaware of them, but I feel that I have spent a weirdly significant portion of my life driving near or around prisons. They seem to be both ubiquitous and highly inconspicuous. I’m sure ours is not the only state that is like this (if you’re from Texas you probably rolled your eyes straight through the last two sentences), but if it is shocking to you that five maximum-security convicts were able to walk off of the grounds as casually as if they were taking their dogs out in Park Slope, consider the jarring “Correctional Facility Area” signs dotting our major highways, warning drivers not to pick up escaped-inmate-hitchhikers.

MARIE WALSH

If you’ve heard of any of the escapees on this list, it’s probably Marie Walsh. For one thing, “Attractive Blonde Lady With Secret Life” plays pretty well on the talk-show couches, and she did go on to write a memoir and interview with Oprah, as any sane person in her position would. What makes her story legitimately gripping is the implausibility of both the escape and her success as a fugitive.

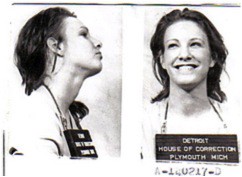

Marie Walsh (née Susan LeFevre) was arrested at age 19 when she sold heroin to an undercover officer; she pleaded guilty with the understanding that she would get probation, but was instead sentenced to 10 years. One day when she was sitting in the Detroit House of Corrections, her twenties laid out before her like concrete bricks in a wall, her grandfather came to visit. “Susan,” he said, “you have to get out of here.” She was dumbstruck, according to her book, but agreed. So they hatched their plan.

One year and 19 days into her sentence, Walsh’s grandfather waited in his sedan outside the prison while Walsh scaled a 20-foot barbed wire fence and sprinted towards him, a search helicopter circling overhead. She made it to the car, where she found her grandfather saying a rosary for her, with a gash in her hand from the barbed wire that would become a permanent scar. They drove to Walsh’ mother’s house, where Walsh took some cash and said goodbye. The escape then became her life.

Walsh shed her identity as Susan LeFevre on the road out west. Once in California, rather than developing agoraphobia (as I probably would have), to avoid something life-ending like a jaywalking ticket or an old acquaintance, she walked straight into the belly of the beast: the DMV. She applied for a driver’s license with a made-up social security number, and was, unbelievably, approved. She pulled the same trick to get jobs, but inevitably her various bosses would call her over with a paperwork problem, and she would have to skip town.

For 32 years she lived like this, quiet but skittish. She didn’t even reveal her secret to the man she married in 1985, nor to their three children. Finally, in 2008, her fugitive life ended in total anticlimax. The feds received an anonymous tip and arrested her outside her home. She pleaded guilty, and perhaps because she was now a wealthy suburban homemaker with a family, she got the probation that Susan LeFevre, the 19-year-old with the dealer boyfriend, had been denied.

SARAH JO PENDER

When I started reading about Sarah Jo Pender, I was planning to file her escape under Batshit Operations along with Sarah Lopez’s and Marie Walsh’s. After all, Pender was convicted for the double-murder of her roommates, was featured on America’s Most Wanted, and has had the epithet “the female Charles Manson” stitched to her name. But the genius of her escape was that it was boring: a well-timed, calculated manipulation of her environment.

First, Pender charmed Scott Spitler, one of the corrections officers at Rockville Correctional Facility in Indiana, where she was serving 110 years. Evidence of Pender’s compelling personality is just as prevalent in coverage of her story as the demonizing portrayals and nasty adjectives. The Daily Mail manages to exemplify that dichotomy within one article: a veteran journalist visits Pender in prison, declares her “not as bad as they say” and poses with her in a picture; meanwhile the journalist covering the interaction writes with contempt that his colleague was “warned” about Pender and “admitted” to sympathizing with her. According to Pender herself, a Chicago officer once told her, “you are the nicest person we have ever arrested.” However, the conniving seductress narrative that is so played up — including in the TV-movie adaptation of Pender’s story, subtly titled She Made Them Do It — doesn’t totally jibe with reality. Pender did in fact promise Spitler $15,000 for his troubles, just to be sure.

In the days before her escape, Spitler provided Pender with a cell phone, cell phone charger, and civilian clothes. She changed clothes in the prison gym, leaving her uniform above the ceiling tiles, and walked to the prison vehicle fueling station where Spitler was waiting with a van. She did all of this in plain view of the surveillance cameras, which facilitated Spitler’s almost immediate arrest following her escape.

The scheme hinged not only on Spitler’s cooperation, but also on basic human sloppiness. Spitler guessed that if he got out of the van and walked up to the guardshack himself, the guard wouldn’t search the van before it left the premises. He was right. Once outside, Pender’s friend Jamie Long picked her up and drove her to the eastside of Indianapolis. Within days, Spitler had been identified, Long had been apprehended, and Pender was halfway to Chicago, where she would settle into a quiet job and hold her breath until her re-capture four months later.

LIMERICK GAOL

My personal favorite escape story is that of nine women and an infant from Limerick Gaol (Prison) in Ireland in 1830. It is one of the Internet’s greater cruelties that, other than a short report from the long-defunct Monmouthshire Merlin, very little information is available about this escape. The Merlin reported that nine convicts — including four Marys, two Margarets, and an 11-month-old baby belonging to one of the Marys — escaped just hours before they were to be transferred to a prison 60 miles away.

The inmates enlisted the help of two men from outside to break the locks on their cells. They knew this would be a noisy job, so the men waited until the evening, when the prisoners would typically break into song together, presumably because they were bored and the television hadn’t been invented yet. On this particular night, to disguise the sound of enormous iron locks being banged off of the bars with hammers, our nine heroines simply sang super loud. According to the Merlin:

This amusement [singing] they enjoyed with more than ordinary spirit on this occasion, and without exciting any particular notice. Meantime the iron fastenings were assailed by the burglars with extraordinary success; the continued knocking was heard in the adjacent ward, but the sound of their operations was so drowned in the melody of the accompanying voices as not to reach the ears of the gaol governor or his assistants.

Women and baby later shimmied out, hopped the barriers with the aid of a ladder, and fled into town. The Merlin makes no more than a passing mention of the smuggled baby, although the fact that said baby remained quiet enough not to betray the escape while it was being passed over the prison walls like a medicine ball is almost more incredible to me than the singing scheme itself.

IF YOU’RE COUNTING

Escapees: 17

Reported Recaptures: 9

Remaining in Prison: 1

Planned and released movie adaptations: 2

Jackie Strawbridge is a teacher in New York City. She has watched Orange is the New Black four times through.