Scandals of Classic Hollywood: The Most Kissable Hands of Pola Negri

by Anne Helen Petersen

Pola Negri looked like something from a storybook: she had jet black hair, pale skin that reporters compared to a camellia blossom, and a sensual mouth that, painted bright red, read as something deep and mournful onscreen. She was Polish by birth and Hollywood’s first foreign import; the Czar of Russia once said she had “the most kissable hands in the world.” To American audiences, she was exoticism manifest: an amalgamation of connotations that added up to different, not us. That exoticism was fiercely appealing — five years before Negri came to Hollywood, it had made Theda Bara into a massive star, at least until the public figured out the creature who had been borne of a woman and a serpent on the banks of the Nile was really just from Ohio. But Negri was the real deal: her father may not have been a serpent, but he had been a rebel fighting the Russian army, and Negri had royal blood in her veins and a title, acquired through a doomed marriage to a Polish count, still lingering in front of her name.

But Negri was more than an accumulation of skillful publicity. The girl could act, and her willingness to throw herself into her characters — to let the full spectrum of emotion wreak havoc with her body — was what first enamored her to the American public. But that emotionality, and Negri’s willingness to exploit it, soon became too much. By 1926, she was involved in a farcical relationship with Rudolph Valentino; when he suddenly died, she prostrated herself the foot of his grave and arranged for a fake note from the doctor to declare that his last thoughts had been of her. It could’ve made for a very successful film, but played out in real life, it became ridiculous, and Negri became a punchline. Today, Negri’s beauty seems otherworldly, untranslatable. But in the ’20s, those kohl-lined eyes sent shivers down spines.

The details of Negri’s childhood are contradictory and somewhat murky. A fan magazine claimed she had the “paradoxical distinction” of being one of the most famous and yet least known of all stars: everyone knew her name, but no one knew her story. Some claimed she was a courtesan; others thought she was an ordinary German shop girl named “Pauline Schwartz.” But Negri’s mystery was part of her appeal — her image was a blank slate onto which audience members could map their most exotic fantasies.

Indeed, when her films first made their way to America, all audiences knew was that the films were German and starred a woman with dark, stormy features. The name “Pola Negri” held no clues: Negri was Italian; Pola could be almost anything. Even after Negri clarified her history, this pan-exoticism would cling to her image. It wasn’t entirely untrue: Negri’s parentage and class made her a member of the cosmopolitan Eastern European class; when she came to America, she supposedly already spoke five languages. Negri’s mother, Eleonora Kielczewska, was from one of the oldest families in Poland, but was ostracized for choosing true love over blood and marrying a Hungarian gypsy.

In truth, Negri’s father was a Slovak immigrant tinsmith and her mother’s family was old, but they had little money. The rich girl marrying the handsome gypsy, however, was much more befitting of Negri’s image. In 1894, Eleonora gave birth to a daughter, naming her Apollonia Chalupiec, or “Pola” to her intimates. Years later, Pola would jettison her last name in favor of “Negri,” which she borrowed from the Italian poetess Ada Negri — a perfect melodramatic touch.

When Negri first arrived in the United States, the narrative of rebellion, resilience, and independence was deployed to manufacture sympathy and, in the process, deflect from any xenophobic protests of a “foreign import.” In 1922, just months after arriving, her description of her childhood travails was almost cinematic. As Negri told The Boston Globe, her father joined forces with the Polish rebels rising up against the Russian rulers in 1906. For his dissidence, he was sent to Siberia where, in Negri’s words, “he died, heartbroken and in misery, like thousands of his compatriots.”

After her father was captured, Cossack soldiers came to her childhood home and began shooting out the windows; she and her mother hid, but the soldiers broke down the doors, where they eventually discovered the pair huddled under the bed. The soldiers dragged them outside and accused them of being revolutionaries, but didn’t kill them — instead, they looted the house and forced mother and daughter to watch as they burned it to the ground. “Out of the ashes” of their home, however, “emerged a New Pole.” Negri wanted to go fight her father’s fight, but as she explained, “I was born Apollonia and while men must fight… women must weep.”

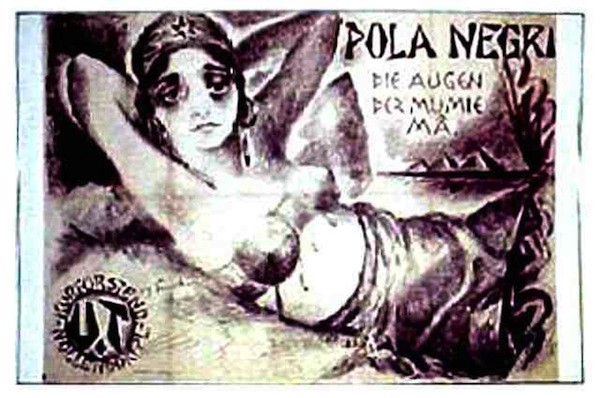

According to lore, Negri’s mother scraped together enough money for the pair to move to Warsaw, where Negri won a place in the prestigious Warsaw Ballet Academy. She appeared in Swan Lake, fell ill to tuberculosis, and while she was recuperating in a sanitarium, came up with the brilliant pseudonym of Pola Negri. It was, I can only imagine, a teenager’s dream: success, illness, a chance to come up with a brand new identity, and the triumphant return. She won broad acclaim for her turn as an exotic dancer in the stage production of Sumurun and appeared in a smattering of Polish films. By 1917, Warsaw was assailed on all sides and Negri fled to Berlin, where she was cast in famed director Max Reinhardt’s filmic adaptation of Sumurun. She wasn’t the star, but she was onscreen — and striking enough to catch the eye of the young director Ernst Lubistch, who convinced his studio (German powerhouse Ufa Films) to produce the amazingly titled Die Augen der Mumie Ma (The Eyes of the Mummy Ma) with Negri at its center.

Negri and Lubitsch would go on to make five films together, each more rapturous than the one before. Madame Dubarry (1919) tore through Europe, catching the attention of American distributors. At this point, Hollywood was enforcing an embargo on all German films — remember, this was a year after the end of “The Great War” — but Dubarry promised millions in exhibition. Renamed Passion, it not only broke the embargo, but sparked a huge demand for German product.

Negri was beautiful, but beauty alone couldn’t have broken the embargo. It was all in the way she acted or, more precisely, the way she didn’t act like her American counterparts. In 1919, D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms had proven an enormous hit — but Griffith’s technique for filming his star, Lillian Gish, was all soft focus and gauzy lens. Gish looked gorgeous all the time, and from that point forward, every actress in Hollywood demanded the same treatment. The result was a slew of films in which the female protagonist basically looked like she was in glamour shots from the mall circa 1988: all surface, zero substance.

One critic called it the “prettifying” effect “thoroughly banal.” If Hollywood films were glamour shots, then Negri’s were like unflattering Instagrams, with the gothy contrast feature turned all the way up. “If she had to rave, she raved; if she had to laugh or cry, she laughed or cried,” proclaimed Photoplay, “and she didn’t care whether the emotion made her look pretty or ugly. She delivered the goods.” She could look “hideous” and “nearly ghastly,” but American audiences had been “so surfeited with underacting” that Negri seemed palpably real in comparison. As film historian Alexander Walker put it, in her Lubitsch films, Negri seems to be “a wild, open-air creature with no time for the gauzy cobwebs of her soft-focused American sisters.” Vaseline on the lens was for vain pansies; real sexiness came from a willingness to bare all.

Just delivering the goods.And once Negri opened the American door to German product, it couldn’t be closed. Suddenly, German films, with and without Negri, seemed to be dominating the market. But instead of freaking out, Hollywood — or, at the very least, Famous Players-Lasky, later known as Paramount — got smart. Instead of fighting the competition, they started to poach it.

In 1922, the studio laid plans to bring Negri and Lubitsch stateside. But they had to be careful: there was still tremendous anxiety about German “imports,” and much had been made over the apparent “riots” that had accompanied a Los Angeles screening of German Expressionist The Cabinet of Caligari. As Famous Players executive Adolph Zukor put it in a telegram to another exec, “WOULD BE VERY BAD FROM ALL ANGLES BRING OVER MORE THAN ONE AT A TIME. SHOULD LEAVE REASONABLE PERIOD BETWEEN TO AVOID PROPAGANDIST CRITICISM AND BE SURE MAKE NO PROMISES.”

(Let’s pause to emphasize that telegrams were “ruining” English long before texting and Twitter, and by “ruining” I mean making it awesome and all caps.)

Negri arrived in New York in September 1922, but before Lubitsch made arrangements with Famous Players, he was picked off by Mary Pickford, who was eager to collaborate with a director who could revamp her juvenile image. The separation worked well: this was no German invasion, just a small trickle of much-desired talent. Negri’s first weeks were a whirlwind of publicity, but with two implicit, if somewhat contradictory, goals: 1) reify her exoticism and 2) establish her Americanism.

Negri knew little English but nonetheless insisted on penning a letter to tell the press her thoughts on arriving in America: “Yes, I am in New York, and what is more important to me, New York is in my blood,” she supposedly wrote, “Here is a real city — Warsaw, Berlin, even Paris seem like [provincial] towns compared with it. And here is my new home.” I smell some publicity bullshit, but no matter: by pairing pieces like this with tales of the Cossacks burning down her house, Negri was made to seem fascinating, never threatening. In many ways, she was the ideal immigrant: proud of her heritage yet eager to build an American identity on top of it.

But once Negri made her way to Hollywood, Famous Players had to figure out what to do with her. They already had a huge vamp of a star in the form of Gloria Swanson and, at least for the time being, Pickford had the monopoly on Lubitsch. What’s more, the entire industry was on guard after the one-two-three punch of the Fatty Arbuckle scandal, the Thaw-White Murder, and Wallace Reid’s treatment for opiate addiction which, in January 1923, would result in his death. Will Hays has been enlisted by the MPPDA and was prepared to ban anything that threatened to further screw with Hollywood’s image. Negri could be a vamp, then, but she couldn’t be a Swanson vamp, nor could she be as suggestive as she had been in her German films. A vamp with a moral ending: the most annoying of character frankensteins.

With her image in flux, Negri’s American films never enjoyed the popularity of her German ones. Over the course of the next five years, Famous Players would tinker with the director, the narrative, even the emotional quotient, trying to hit the sweet spot that had been her so electric in those early films. But it never quite worked the same — in part because they gave her some of the soft-focus glam up that was the antithesis of what had made her a star, in part because she wasn’t with Lubitsch, and in part because the vamp had lost its cultural resonance. So Famous Players-Lasky did what a studio always does when a star property doesn’t seem to be working: they manufactured some glorious, preposterous, absolutely delicious publicity.

Having already exploited Negri’s family background, it was time to move on to the Duke ex-husband, a murky figure who not only gave Negri a prestigious title, but also an amazing story: back in her German film star days, she had ventured home to Poland. Attempting to return to Berlin, she had been stopped at the border, where customs officials demanded she leave her jewels, on which she had conveniently “forgotten” to pay the tariff. Negri was livid: she was needed in Berlin that very hour — and she would never leave her jewels. She demanded to see the commandant, and the terrified customs officials showed her to his office, which she burst into like the pissed off over-privileged young 20-year-old that she was. The commandant stood up; Negri moved to bum-rush him, but suddenly, she stopped in her tracks: “My God, I love him!”

The commandant was Count Eugene Dambski, commandant of Sosnowiec, and he just happened to have a fairytale castle. Negri, in turn, just happened to finagle herself an invite for dinner that night — jewels in hand — which turned into a 10-day love fest, during which they most definitely did not have sex. She was supposed to be back in Berlin for the picture, but this was her chance to craft a plot even more beguiling than her next film. Four months later, she became the Countess Apollonia Dambska-Chalupiec, but their Chris O’Donnell/ Drew Barrymore mad love (sorry millennials, this reference isn’t for you; go spend some time in 1995) lasted about as long as their Honeymoon. Negri returned to Berlin, the Count returned to his Count activities, and after a long separation, the two were officially divorced in 1922. Even if the title was no longer officially hers, Once a Countess, Forever a Countess — that’s the type of royal adventure narrative that never leaves you or your image.

But you know what’s even better for a career than a Count as an ex-husband? A good old fashioned girl fight. This one was almost entirely Famous Players’ doing: when Negri first toured the studio lot, the papers reported two different and equally hilarious stories. In the first, Negri was marveling at all the on-set amenities when a small building caught her eye: “What a nice leetle house. Whose leetle house is zat?” The execs told her that the building was Gloria Swanson’s dressing quarters, to which Negri replied, “Ah, yes, and where will be my leetle house? If Mees Swanson has a leetle house, Mees Negri also has a little house, yes?”

Negri was probably just wondering when and where she got to sit down, but the press framed it as an attempt to put herself on the level of Swanson, who just happened to play a similar sort of vampish role. The second on-set story was more damning: when Negri was eventually given her “leetle house,” it just happened to be the one that had belonged to Mary Pickford. Pickford had left Famous Players years before to start United Artists, but her dressing quarters had remained vacant in a sort of deference to the memory of “Little Mary.” The story had the exotic, vampish girl quite literally taking the place of America’s sweetheart: today, it’d be like Mila Kunis taking Julia Robert’s trailer.

Note to Pola: Do Not Steal This Lady’s Dressing Room.

And then there was the business of the cats. When Negri arrived on the Famous Players-Lasky lot, it was swarming with cats. According to the gossip columns, Negri was superstitious, and thought cats — and especially a roaming pack of cats — were bad luck. (I feel you, girl. I feel you.) So she did what any top star would do: she demanded they be taken away. LITTLE DID SHE KNOW: those cats were Gloria’s cats. Gloria’s cats! I mean, she didn’t own them, per se, but they were “her wards” — she took on a cluster of them early on, and then they just kept multiplying. Did it spark an actual fight? Probably not. But the fan mags loved it: “When Miss Swanson heard of the request of Miss Negri, there were some sizzling things said — some crisp messages exchanged in words that crackled. The cats are still there.”

Note to Pola: Do Not Mess with La Swanson’s Cats.With the cat fight still in the air, Famous Players-Lasky held a lavish banquet. All the execs, all the players, all the stars. When everyone took their seats, there were two conspicuously open seats, each sandwiched between a pair of executives. The first course was served, and suddenly “there was a sibilant sound, a craning of necks and a hush,” as “a gorgeous creature with a wide golden band about her raven hair” entered the room: “It’s Pola Negri! It’s Pola Negri!”

It was an entrance indeed — “the cynosure of all eyes” and Negri took her seat beside President Zukor. (I like the entrance, but I love that fan magazines were using words like “cynosure” even more). But there was still an open space. The first course was cleared; the whispers grew louder. And suddenly, there was Gloria Swanson, walking with her chin up and full-on bitchy resting face the way only La Swanson could. As for Pola’s entrance? Totally forgotten.

Now, according to Swanson, this was all ballyhoo: in the delicious Swanson on Swanson (get on that), she spends two pages disabusing the reader of any rivalry. They barely knew each other, Swanson claims, and it was just the studio’s way of generating interest in both of them. Truth be told, she even invited Negri over for a very subdued dinner party, but no one knew about it because, according to Swanson, she was not in the habit of publicizing her intimate social gatherings. (Even 60 years after the fact, POINT: SWANSON.)

Whether or not the feud was legitimate, Negri’s foreignness had marked her as an interloper from the beginning. While highlighting the feuds, the press also framed her as a Hollywood outcast. One fan magazine report claimed that Negri had but one female friend — the wife of her director, Mrs. George Fitzmaurice. As for everyone else on the lot, they hated her. But it wasn’t her fault: “she came here prepared to like everyone,” but she also arrived in “entire and pitiful ignorance of the jealousies and heartburnings of the other Lasky women stars.” In other words, she didn’t realize the stew of girl shit she was about to stir. A Photoplay story entitled “The Loves of Pola Negri” only amplified this discourse, framing her as “La Negri,” “a tiger woman with a strange slow smile and a old-world lure in her heavy-lidded eyes.” As a “Nietzschian woman,” she excited man’s natural appetite for danger and play with her “threat of instinctive cruelty.” The overarching message: men flocked to her; women loathed her.

It’s a familiar Hollywood scenario — something very similar played out a decade later with Jean Harlow — but it should also be familiar to contemporary audiences. Feminist scholar Angela McRobbie calls it “romantic individualism”; the term describes the way women use competition for men to divide and effectively neuter any potential political power. It’s a brilliant strategy on the part of patriarchy: instead of dealing with women, why not just encourage them to fight with each other? Maybe they can even fight about which of them gets to hang out with dudes more? Romantic individualism isn’t innate to civilization — it’s an ideology like any other, predicated on a certain understanding of monogamy and, somewhat weirdly, free market democracy (may the best woman win). But part of the way it endures today is through media representations. On the screen, on the gossip page, on Gossip Girl — we’re taught that the best use of our time is fighting over men, and that women who attract men’s attention should be shunned and labeled whores.

If romantic individualism instructed women to distrust Negri when she arrived, they distrusted her even more when she took up with Hollywood’s most eligible, most successful bachelor: the recently-divorced Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin first met Negri on his “grand tour” of Europe, and at some point after their meeting — which must have taken place through an interpreter, or through meaningful glances — an interviewer asked Negri about her thoughts of Hollywood stars. “American motion-picture actors?” she responded, “I have seen only one — Charlie Chaplin. I think he is very nice.”

And that was it, at least until Negri arrived in the states, at which point the rumor mill began churning. By November 1922, everyone was “agog” (another awesome word from the fan magazines of the era) over the possibility of a Negri-Chaplin romance, with speculation fueled by Negri’s insistence on a marriage clause in her contract that would release her from all duties on her wedding day. Negri protested that she wasn’t about to get married — “I live only for my art!” — but it was all a bit too suspicious.

Some thought it was a blatant publicity stunt; the Queen of Tragedy paired with the King of Comedy sounded just a little too neat, after all. But it was all that anyone could talk about: not even the engagement of the Prince of Wales could top the rumors of a Negri-Chaplin romance, especially when they spent some very high-profile time frolicking around Santa Barbara (fully chaperoned, of course), playing golf and wearing natty sporting sweaters.

But it wasn’t until they attended dinner at the Governor’s house in January 1923 that they finally admitted to a potential engagement. Blasted with questions, Chaplin put his arm around Negri’s shoulder, blushed, and admitted “that some day there would be a Mrs. Chaplin number two, and that Pola was the gal.”

It’s unclear how much of this romance was publicity stunt and how much was simply the ’20s style of dating, in which any dalliance that lasted over a month turned into an “engagement,” mostly to justify hanging out together and a little behind-doors sexytime. Chaplin and Negri could’ve been a Hollywood power couple to rival Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, but less than two months after the engagement announcement, Negri unceremoniously broke it off. The headlines — “CHAPLIN JILTED!” — were bad enough, but Negri’s explanation was some next-level shit: “Charlie appealed to my mother complex. And his personality interested me. I study — I study — and then I study too much!” She told the Los Angeles Times that there were “a thousand” reasons not to marry Chaplin, including the fact that she was “too poor.”

Chaplin’s response: “Oh.”

With the end of her engagement, Negri vowed that she would live only for her work — “the happy days at Santa Barbara” were dead to her. That sounds like something I would say about a boyfriend after finding out he was really into Christopher Nolan films, but those were Negri’s actual words: “dead to me.” The whirlwind romance and Negri’s tendency towards hyperbole cemented an understanding of her off-screen persona as an extension of her on-screen performance. She was the Queen of Tragedy on-screen, she was the Queen of Dramz off.

For many stars, this type of conflation is a recipe for success. Look at Gary Cooper being all Gary Cooper-ish hanging out with Hemingway in the woods, or Marilyn Monroe’s performance of innocent sexuality in “real” and filmic life. When done right, it doesn’t look like publicity — it just looks like the star being him or herself. But there’s a tipping point, a moment when the publicity goes too far and the seams of image construction become visible and, by extension, ridiculous.

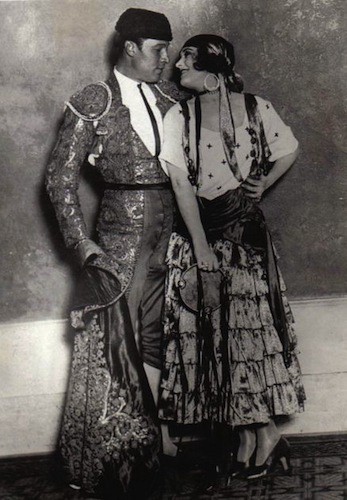

This type of faulty construction usually happens on one end of the star’s tenure: in the beginning, when he/ she and his/ her studio is trying to make a name for the star (the fake stories of Lana Turner’s “discovery” at a soda pop fountain) or at the end, as the star wanes and desperation grows. Today, it’s visible in every jump Tom Cruise made on Oprah’s couch or every televised wedding Kris Jenner arranges for her daughters; in the 1920s, it inflected every move Negri made. Part of the problem was her studio’s inability to figure out a role that worked for her. She’d made her name with her overwrought, vampish German films, but in these films — especially with Lubitsch behind the camera — Negri didn’t seem over the top, she just seemed real. But Famous Players-Lasky never quite replicated the formula. Her first two films, Bella Donna and The Cheat, both released in 1923, were fine, but nothing compared to the tremendous success of her German films. Her next film, The Spanish Dancer, was based on Victor Hugo’s Don Cesar de Bazan. But you know what else was based on Don Cesar de Bazan? Mary Pickford’s new film, directed by… Lubitsch. It’s like the epic mid-‘90s battle of Chicago Hope vs. ER, with Negri as Mandy Patinkin and Pickford as George Clooney. You can just guess whose version endured in the popular imagination.

Negri recognized the downward trajectory of her career and arranged for Lubitsch, freed from his contract with Pickford, to head up her next film. The result — Forbidden Paradise, in 1925 — featured Negri as a very self-serious, very well-costumed Catherine the Great, and gave her all manner of opportunities to exchange steamy looks and open-mouth kisses with Rod La Roque, a.k.a. the man with the best name in the history of silent cinema.

Paradise was well-received, but this was also the year of Clara Bow’s breakthrough film, The Plastic Age. Bow represented the future of female stardom — ebullient, fancy-free, fresh-faced — making Negri, with her heavy-lidded emotionality, look dour and performative. She was like the sad, over-dressed girl crying in the bathroom at the party filled with perky-breasted freshmen.

Famous Players-Lasky knew that they needed to switch up her image, so they did two things: first, in A Woman of the World (1925), they lampooned it, which at least made it seem like Negri was in on the joke. In Good and Naughty, now lost, they had her “play ugly” in a scheme to get a job, and in Hotel Imperial (1927), she was cast as a peasant.

The opposite of Catherine the Great in Hotel Imperial.It was an about-face, and it might have worked to change the trajectory of Negri’s image, if not for her very public and very ridiculous dalliance with a star equally busy trying to salvage his own career: Rudolph Valentino.

It wasn’t as if this was Negri’s first romance. In addition to her instant-husband the Duke, she also had a long-term lover while living in Germany, and after breaking things off with Chaplin, she was publicly linked with La Roque. (Amazing rumor: after jilting Chaplin, she gifted LaRoque with her $15,000 engagement ring). But just when she was trying to turn her image into something that was more “just like us” than “Countess dripping diamonds,” she started hanging out with Valentino who, at that point, connoted about the same thing that Justin Bieber connotes now: teen idol gone terribly sour.

For a short period of time, Valentino was the alpha and omega of male stars, the most handsome, incendiary thing on the screen. It’s a convoluted story of how he went from a “Taxi Dancer” (read: gigolo) to leading male heartthrob, but suffice it to say that as the “Latin Lover,” he was thoroughly feminized. His turn in The Sheik drove women to cry and convulse in the aisles, and he had a HUGE ego. (Suffice it to also say that I have a chapter on Valentino in Scandals of Classic Hollywood: The Awesome Book).

When he met Negri, he was in a tight spot: after the tremendous success of The Sheik, he had spent all of his artistic and cultural capital fighting his studio and participating in a hilariously messy divorce. In a state of desperation, he reluctantly agreed to film Son of Sheik, reprising the role that had made him famous, but which he had come to despise. It’d be like Robert Pattinson, frustrated with the lack of Cosmopolis success, agreeing to do a Twilight reboot.

Valentino was pissed. He was also pompous, and that’s the place he was in when he met Pola Negri, supposedly at a costume party hosted by William Randolph Hearst and long-term mistress Marion Davies. According to Negri’s memoirs, the resultant sex was hot and heavy: “after we dined,” she recalled, “he stripped the petals from each rose blossom, strewing them over my bed. The petals were as soft as a velvet coverlet beneath our bodies… and together on this floral bower we rejoiced until dawn broke.” Negri wrote this something like six decades after the (f)act, but to everyone who’s out there rejoicing ’til dawn: if you don’t have a blanket of rose petals, UR DOIN’ IT WRONG.

In February, rumors began to circulate that the pair would meet in Gallup, N.M., and elope. Valentino’s train, coming from the East, would meet Negri’s train, coming from the West, and they would duck away to make things official. But once the press caught wind of the plan, it descended on Gallup. Valentino never got off the train, and Negri claimed she was just there to investigate the oil business. (There wasn’t an oil well for miles.)

A miscommunication? Sure. But the hoopla over the potential meeting, and Negri’s transparent denial of it, made the pair into a gossip punching bag. And if that seems a bit trifling, don’t worry, it gets more ridiculous from here: a month later, Negri embarked for a four-month stint in Germany with hopes of resurrecting her faltering career. Valentino was stuck in California shooting Son of Sheik, so Negri announced that they had decided to undergo a “supreme test of love” — if they both felt the same in four months, then “there is nothing to prevent the marriage.”

“I think he is the supreme man,” Negri confessed. “He is perfection.”

But were they engaged? Not really. Negri said she “didn’t like labels,” which is a phrase that should sound familiar to anyone who’s tried to date a dude between the age of 17 and 27. And as for Valentino, he flat out denied even having heard of an engagement. When Negri returned from Germany, it seems that they resumed their relationship, but Valentino was quickly embroiled in the most hilarious scandal of his career. Again, you’ll have to read the book, but it involves a powder puff dispenser, an anonymous editorial, and Valentino’s very public call for the author of said editorial to face him in the boxing ring.

But before any boxing could take place, Valentino collapsed in his hotel, suffering from appendicitis and ulcers. He had surgery. Things seemed like they were going to improve for him — the doctors told everyone as much — but when he took a turn for the worse, those same doctors withheld the prognosis from him. In the hours before he slipped into a coma on August 23, 1926, he was supposedly chatting about his future acting prospects.

When Valentino died a few hours later, few had known just how serious his condition was, including his quasi-maybe-on-hold fiancee, Pola Negri. When the news reached Negri at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, she fainted. After she revived, she was so distraught that she was put under doctor’s care, with a nurse in constant attendance. Valentino’s death was front-page news, but Negri’s mourning became just as prominent a story. She boarded a cross-country train to attend the funeral, where she (supposedly) arranged for wreaths of flowers to spell out P-O-L-A on the top of the casket.

None of the reports from the time talk about this flower arrangement, but almost every telling since does. Whether or not it was there, it fits with the narrative of Negri’s funeral appearance, which featured a lot of prostration and wailing and rending of garments. There was some whispering speculation as to whether the pair were, in fact, engaged, and whether Negri’s emotion was, in fact, genuine. Negri refused to speak directly to the press, but sent a message from her cloistered hotel room:

I am happy that everything has been made so lovely for Valentino in death. We were really engaged to be married, but the fact that we both had careers to follow accounts for this delay in our wedding plans. My love for Valentino was the greatest love of my life; I shall never forget him. I loved him not as one artist might love another but as a woman loves a man. I loved the irresistible appeal of his charm — the wonderful enthusiasm of his mind and soul. I did not realize how ill he was or I would have been here before his death; he kept the seriousness of his illness from me.

I mean, I kinda buy it? Or at least I would’ve, if not for what happened next. Amidst continued speculation, Negri proffered a letter supposedly penned by Dr. Harold D. Mecker, who had been at Valentino’s bedside for his final hours. According to the note, Valentino had awoken at 4 a.m. and uttered, “Pola — if she does not come in time, tell her I think of her.” If Negri’s story is to be believed, Mecker had recorded the words in a note, which he had then given to Mary Pickford to pass along to Negri, who then presented it to the press, sobbing, “This was his last message to me.” She was then escorted to bed by a nurse.

Now, everyone grieves differently, etc. etc., and I don’t mean to suggest that Negri wasn’t enormously upset and unmoored by Valentino’s death. The problem is that she did all that grieving in public, and invited reporters along for the ride. The press had already needled her for the will-they-won’t-they antics in New Mexico, but they outright lampooned the (somewhat obviously contrived) letter and subsequent efforts to publicize her grief. Back in Los Angeles, she took a reporter on a melodramatic tour of Valentino’s home where, weeping, she staggered from room to room, calling Valentino’s name.

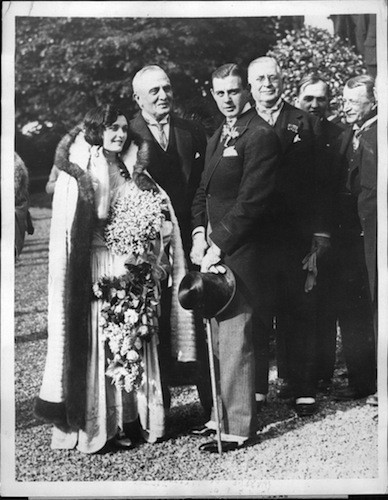

It was a performance that would’ve fit right in with her German films, but those films had already gone stale. And any goodwill towards her broken, grieving heart was negated when, six months after Valentino’s death, she announced her engagement to the Russian Prince Serge Mdivani. He’d known Negri since they were teens; his father had been a Russian General, and he was filthy rich from oil money. He was also handsome, sure, and Negri got an amazing wedding get-up that no Pinterest wedding will ever replicate — but still, too soon, girl. Too soon.

Barbed Wire underperformed, and Negri rode out the end of her Famous Players-Lasky contract (by then known as Paramount) with a string of similarly uninspired films, all of them now lost. She probably saw that her heavily-accented English wouldn’t do well with talkies and, finding herself pregnant, announced her intention to retire and devote herself to her family. But in short order she had a miscarriage, found out that her rich Russian Prince was, in fact, a semi-broke Russian Prince intent on emptying her bank account, and returned to the screen for an elaborate British production.

Negri began divorce proceedings against Mdivani in 1930, but during the process, a peculiar story came to light. A Spanish painter by the name of Beltran Masses filed suit against Negri, alleging that she’d failed to pay him the $5000 she owed for a commissioned portrait. Negri countered that he’d come to her and volunteered to paint the portrait, but what really matters here were Negri’s instructions for Masses: he was to paint her as she was, but he was to add a wraith of Valentino in the background. A ghost! Of Valentino! In the back of her portrait! I have read a TON of bonkers Hollywood tales, and that tops it all. Pola 4 Life, and my kingdom for that portrait.

So she settled accounts with the painter, divorced Mdivani, and then disappeared for a bit with her Valentino wraith. In 1932, she returned to Hollywood to take a chance on a talkie called A Woman Commands. It did OK, but the real revelation was Negri’s singing voice: her rendition of “Paradise” became a monster hit, and she toured the country promoting it.

It was the beginning of a solid second act to her career, and she returned, with great fanfare, to Germany. The only problem? Hitler loved her movies — Mazurka (1935) in particular — which prompted rumors of a potential liaison between Negri and, you know, the Fascist ruler of Germany. But Negri successfully sued the papers propagating the rumors and simultaneously negotiated a new contract that would allow her to live in France and still make German films.

But after Germany invaded France, Negri got the hell out of Europe. She came back to Hollywood, did some American vaudeville, and rekindled a friendship with an old friend/ actress/ oil heiress, who convinced her to move to San Antonio, where they could be Golden Girls together.

And so they did, and so they were: ignoring the world around them, attending to their flowers, and probably wearing lots of amazing caftans. Negri turned down the role of Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard (which, in a twist of beautiful fate, eventually went to Gloria Swanson) and after decades of resisting Hollywood, agreed to a very brief and very odd cameo in the 1964 Haley Mills film The Moon-Spinners. She publicized her return by showing up to a press conference with a cheetah on a leash.

Yet apart from the publication of her memoirs in 1970, Negri stayed almost entirely out of the public eye until her death, at the age of 90, in 1987. Like Theda Bara before her, Negri seems to represent a wholly different paradigm of Hollywood stardom, with radically different understandings of beauty, performance, and acting. But even at the height of her popularity, she was difficult to understand. When a fan wrote to New Movie Magazine in 1931, she expressed both what made Negri so beguiling, and her American stardom so particularly difficult:

Just because Pola Negri was different and her complete self at times, quite a few people in the United States disliked her. How true are her words when she says: “They do not understand me. I am a child of my race, a Slav. I have no the restraint of the Anglo-Saxon.” If they gave her pictures worthy of her talents she would be today at the top of the world with Marlene and Garbo… Welcome Pola, fiery gypsy-artist, and may you earthquake Hollywood like it has never been earthquaked before! Show to the world what Pola Negri can do when Pola Negri does. For heaven’s sake don’t let them tame you into a peaceful uninteresting female.

That fan got so much right. (Whatever happened to you, fan?) Negri demonstrated an inability and refusal to comply to American standards of behavior; the studios demonstrated an inability to find pictures to fit her personality; audiences had to react to and deal with her palpable difference. As the industry’s first “import,” Negri’s career was something of a test: could Hollywood adapt a European image for American tastes? In Negri’s case, not quite. Yet the studios soon refined their image-making machinery, which is part of the reason Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo could succeed where Negri could not. But Negri’s engagements, the swooning, the bombast! Even now, I can’t help but label it as performative, over-the-top, and too much — much in the way critics and audiences did in the 1920s.

In truth, Negri was an unruly woman, marked as other by her ethnicity and her willingness to show “private” emotion in public spaces. And like other unruly women, she was ostracized, by men and women alike, in ways both overt and insidious. But Negri never really submitted to American societal demands: up until the end, she seemed to give zero fucks about any and all attempts to ridicule and dismiss her. She was never tamed, and she was certainly never uninteresting.

Negri lacks the vulnerability that endears so many of these classic stars to our contemporary sensibilities, but that’s what I love most about her: in so many of these star narratives, the subjects — especially the female ones — retreat from Hollywood, abused and mistreated, their bodies and minds a shell of their once vital selves. But Negri, it seems, was never anyone’s victim.

She may have left Hollywood, but Negri rarely looked back, and when she did, it was with a knowing sense of humor — the type of humor that thinks to hire a cheetah for a public appearance. That sensibility unites so many of Hollywood’s unruly women, from Dietrich to Mae West (who, after leaving Hollywood, seemed to live forever). And why not? There were other lives for these unruly, unceasingly interesting women to lead.

Previously: The Ecstasy of Hedy Lamarr

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here, and you can read the Scandals of Classic Hollywood series here.