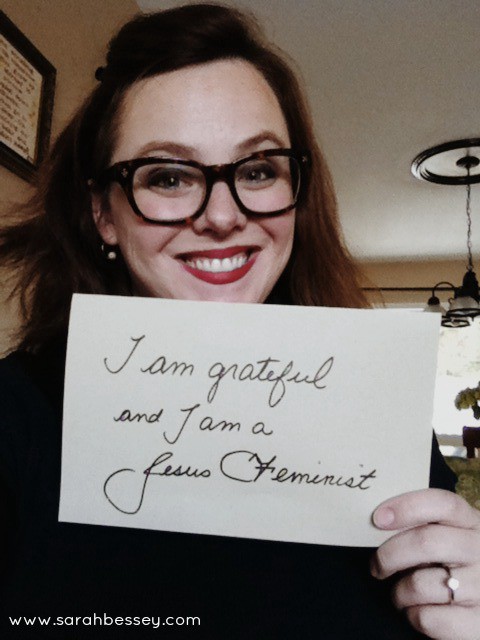

Interview with Sarah Bessey, “Jesus Feminist”

Sarah Bessey is a blogger-turned-author whose newly released book, Jesus Feminist, critically analyzes the Scriptures and church practices that are still often used against gender equality, as well as advocates for more diverse experiences and female leadership positions to become part of the contemporary church. We spoke on the phone last week.

So, how did you end up as an advocate for feminism within Christianity? Walk me through your background?

My background is actually in marketing, communications and strategy development — I was in banks and credit unions for most of my career. But I’ve always had such a passion for women’s issues, which led me towards working in the nonprofit sector. I started working for a local residential home for women who are struggling with life control issues, and I still volunteer there now.

I started blogging in 2005 to keep up with family and friends, but I had this deep desire to write through and process what I believed, my questions, and doubts. I found that blogging really gave people like me a place to speak — people who, within established and mainstream religions, haven’t really had a voice because of gatekeepers or normative culture. I’m not an academic and not a typical leader, but now this is my vocation, to publicly wrestle through theology, motherhood, marriage, politics — things that are often hard to discuss in polite company.

A big part of that has included my reclaiming of the word “feminist.” I grew up in an egalitarian home, attending small churches in Canada where women and men were equally active in ministry, and over time I got more actively engaged in women’s issues within evangelicalism, and advocacy for women’s issues around the world. So the book Jesus Feminist grew organically out of my life and my writing.

Why do you think Christians in particular struggle with the term “feminist” so much?

This may be more specific to the United States, but I think a lot of people experience a really steady diet of stereotypes and fear tactics — this culture war thing. And I understand why that would make you fear and misunderstand feminism.

For me, I was in my early 20s when I began to self-identify as a feminist. I loved having women pastors, seeing women on church boards, seeing women pursuing any life they wanted. So it became a natural thing for me to say I’m a feminist. But then, in the church, when I said it, people would be surprised, and ask these questions — “Do you not want to be a wife and a mom? Do you hate men?” — and they’d ask me what “kind” of feminist I was. I just sort of cheekily started saying that I was a Jesus feminist, a feminist because I love Jesus. It’s from my faith that I treat people with equal value, not the other way around.

Has Christianity always been the driving force in your life?

Well, I was a little bit older, probably around 7, when my parents started going to church. And what they were doing at the time seemed unusual: we had the Christmas and Easter people, but not a lot of the happy-clappy Christians like we became. But yes, that’s how I’ve oriented my life. There are aspects of Christianity and the church that I struggle with even today, but at the core I see myself as a disciple of Jesus.

I should say, I don’t want to die on a hill of labeling. I was initially afraid that the idea of “Jesus Feminist” would just offend everybody. But I really am writing towards primarily people who are in the church, wanting to get them to see the totality of the Gospel, and a way of reading Scripture where God’s dream for humanity is one of wholeness and empowerment — for everyone to be walking free and equal.

Where do those religious beliefs place you, politically?

Well, that’s hard for me to answer depending on the audience — my version of moderate might look very leftist to a lot of Americans. But I don’t want to give people boxes to check off. I think people can bring a lot of beliefs to the table in this conversation — I’m not interested in telling anyone else how to live.

How do you reconcile that with one of the fundamental tenets of Christianity — and other religions too, of course — which is that it is The One Way?

I’ve had a hard time with these issues before. I did struggle with some iterations of evangelicalism in my adulthood, ideas which had never been part of my background. And I distanced myself from the church for some time. I felt very awakened to God’s heart for justice and mercy, which made me struggle with a lot of things I found in some parts of the church: for instance, war, which I was in staunch disagreement with; my beliefs about health care and caring for the poor; my passion for the global story of women as opposed to the Western, North American pocket.

For awhile I just felt like I was finding no answers. So I just cocooned away, like, “I know I love Jesus but man, lots of crazy people out here, and I could use a break.” And in that process I found people who loved Jesus away from the stage and the fancy microphones — they were the ones who loved Jesus right where they were, who disagreed beautifully about their theology, who were humble, who found God in their living rooms. I began to see that Christianity has a long history of disagreement and refinement, and there was room for diversity within the same family.

Do you consider your community pretty exclusively the faith one?

Oh, no. This is my work, but I’m not solely in a ghetto of people who think or act the same way as I do; your world gets pretty small if you start doing that.

A “Christian” marriage is often conceived of as one where the man is the head and the woman is submissive. Can you tell me more about what you’ve written about the erasure of this hierarchy?

Well, this is how my husband and I were raised — both of us are lucky to have parents with long, happy marriages; mine have been married for 40 years and are still quite in love with each other — so, we just went into this with the understanding that we would really value equality, and understand Scripture to point towards that, rather than this idea that the woman submits to the man as the head of the home. With marriage, of course, everyone does it differently, and finds what works for them. But we believe in something called mutual submission, where we submit to each other, and Jesus is the head of our household.

And do people resist you on this?

Yes, certainly, but I find it refreshing. I want to engage with these questions. I can see that if you’ve never been around an equal marriage structure, it can seem very strange, and I have compassion for that. I really can’t imagine living within that kind of restriction, or somehow baptizing it as being more “spiritual” when I believe that it’s pretty much the furthest thing from Scripture’s intent or God’s dream for us. But there’s always pushback, and I’m not too fussed about it.

I’ve been reading a lot on your website, and I think your style of feminism has got to be so deeply appealing to Christians — you don’t present yourself aggressively or cynically, and you talk about trying to recover from cynicism in some of your writing. Have you ever had to adjust consciously to match up with a community that might find feminism much easier to swallow when it’s presented very “nicely”?

Well, anger can be very helpful. I don’t want to approach my work from a point of repressing anything, or tone policing to be part of the club. When I am angry, I’ve found that it’s very indicative of a passion — anger’s sort of an engraved invitation from God to pay attention to something, which for me has always been women: in the church, in the world.

What I do try to guard against is bitterness and hopelessness, and the idea of winning an argument at all costs. Because I start from the position of being a follower of Jesus, that affects the way I engage my feminism. And that can be really freeing for me. I try to enter and exit arguments with a minimum of collateral damage — I don’t want to wound anyone I disagree with. I think there’s a way to move through activism and advocacy that affirms the dignity of people you disagree with.

That, actually, has been something that’s changed for me in the last five of six years. I no longer feel like I’m engaging out of a place of fear or scarcity. I have this well of hope and faith about all of this.

What do you see as feminism’s most urgent work within the church?

The hardest situation is when people really believe that God wants inequality. When they’ve been taught a line that’s been mistranslated and used against people — like, that women should be silent in church — and they absorb this idea that God wants women to be meek, and requires it. There are differences between feminism’s work inside the church and out of it. Inside the church, people can think that their salvation’s on the line. They’re thinking about their actions as affecting eternity, and this makes systems very slow to change.

But the urgency isn’t necessarily restricted to women preachers, either. It’s more about how all of us decide to live into the other side of the answers. Once we’ve settled a lot of the arguments against full equality for women — and I believe it’s important for people to settle those! — then what happens? It’s the “then what?” that fascinates me.

I’m stuck on the idea of an eternal patriarchy. Oh, my.

Yeah! Those stakes are really something. I’ve been speaking in churches that still have these practices, and the thing is, they don’t realize that there are so many Christians who don’t. There are vast swaths, huge traditions, a long history of Christians who have walked in a way that values freedom and equality. They don’t know that there were female apostles like Junia; they don’t know about Deborah, the female judge in in ancient Israel; let alone all these people who have moved through their lives both counter-culturally and within Christianity, for so long.

More about Sarah Bessey and her book Jesus Feminist at her website.

Previously: “Interview with a Pastor on Spiritual Grammar, Mysticism and Coming Out”