How I Found Out I Didn’t Have the Herpes I’d Been Living With for Four Years

by An HSV-Negative Lady

This story is an update to this story, published here in April 2012.

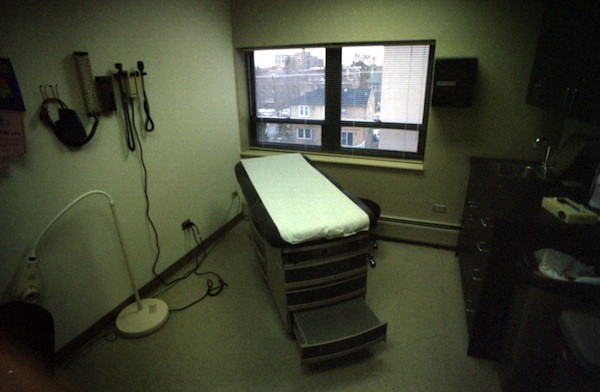

Six months ago, I sat waiting in my gynecologist’s exam room chair, fully clothed and wishing I were anywhere else. At that particular moment, I’d even have preferred being naked and spread-eagled on the paper-lined bed. It’s not true what they say about the stirrups being the worst part of the ladyparts exam room: it’s the chair. Once you’re clothed and in the chair, it means you’re there to talk.

You never forget your first time debriefing with your gynecologist. Mine was four years ago, at age 22, when I sat crumpled in a chair just like this. A few days before, I’d had a rough romp of casual oral sex, a one-night head-stand. Minutes after the guy went down on me, I felt that something wasn’t right with my vagina, and two days later, I broke out in sores. “You poor thing,” the nurse practitioner at my college’s health center told me. “You have herpes.”

“Don’t I need to be tested?” I choked out between sobs. She’d cocked her head and tossed me a pity smile, as if to say, don’t you think I’ve seen enough herpes to know what it looks like?

My sores couldn’t be anything else, she told me. It didn’t matter if it was HSV-1 or HSV-2, because once it presents genitally, herpes is herpes. And it’s mine for life.

I never got another outbreak, but at 22, I still entered the dating world feeling like damaged goods. I was young, healthy, attractive, and grateful to anyone who agreed to fuck me after I told him I had herpes. (Only at first. As I wrote on this site a year and a half ago, herpes eventually helped me become a better dater and gravitate toward decent men.) But the conversation — the “before we do this, I have to tell you something” routine — never got easy. And the diagnosis inevitably warped the way I thought about myself. I no longer felt like a free agent in the world of love and sex; instead, I assumed I’d have to settle a notch or two down from the man who could have loved a herpes-free me. I may never have had another sore, but I still felt marked.

Four years after being diagnosed, I was at the gyno for my annual pap smear when I decided to order the sex-haver’s special: tests for HIV, gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis. I also figured it was time to meet my herpes, so I requested an off-menu HSV blood test that isn’t considered part of the routine STD-screening panel. “If you don’t hear from us by Wednesday, everything’s normal,” the doc told me.

And then the “we found something” call never came. That wasn’t my normal.

I called the lab to see what had happened to my test. “Oh yeah, here you are,” the lab tech told me as she pulled up my record. “You’re negative for everything.”

What.

“No,” I told the tech. “Check again. I definitely have herpes.”

“I don’t know who told you that, but you don’t,” she said. Both of my blood tests for HSV-1 and HSV-2 were negative.

I was mad and confused. I sat with the news for a moment, though, and soon became madly happy and extremely horny. My libido unshackled itself, tore off its scarlet H. Suddenly, every man on the street was a possible conquest again. The idea that I could have sex with anyone I wanted — no preambles, just straight to the sack — was a real turn-on. I sent the ex-boyfriends I’m on good terms with excited “Guess what!!!” texts and eye-fucked on the subway.

It’s funny, but the blood test had finally confirmed how I always felt about having herpes: that I didn’t. But what had happened to it?

Surely, my gyno could tell me. I gathered up my college medical records to show her — a real doctor, I reassured myself, no nurse practitioner. Any minute now, she’d thumb through the pages and declare null and void my four-year-old misdiagnosis. “Wow,” she’d say. “She really screwed that one up.” Maybe we’d even laugh. Then I’d skip off somewhere to have perfect sex.

But first there was the matter of the disappearing herpes.

I brought a notepad, eager to remember every word of my emancipation. “Let’s just see here,” my gynecologist said. She studied my records while I sat with notebook open, ready to right my sex life.

“Well,” she said. “Reading your chart, yes, it really sounds like herpes.”

I stared at her. No, I thought. Didn’t she hear? I’m negative.

“We’re not living in some third-world country,” she continued. “I don’t expect your sores to be some new mutant STD.”

“Then why is my blood test negative?” I asked. Hot tears ran down my face and dripped on my blank notebook. I was pissed. I started transcribing.

“Sometimes the antibodies for herpes just go away, and blood tests can no longer detect them,” she told me as she closed my file.

“Is that the best explanation you have?” I asked.

“I’m not going to lie,” she told me, “it’s a little weird.”

I was being diagnosed all over again, my shiny new sex life ripped from me as carelessly as it had been before. “What am I supposed to tell people?” I demanded.

“As a human being,” she said, “you have two choices. You can go by the blood work, which is negative, but then you risk putting someone else in the same unhappy situation you’re in now.”

She handed my file back to me, as if she felt we were done here. “Or you can go through the act of telling this to everyone for the rest of your life, which is horrific.”

•••

I almost left it at that. I almost kept disclosing.

Just the threat of passing my herpes-in-question along was enough to make me wonder if anything had really changed. But something had changed. I wasn’t about to let myself be misdiagnosed again.

So I called up the world’s leading experts in herpes to ask a seemingly simple question: do I have herpes or not?

Apparently, I’m not the only one who’s ever asked.

“People and clinicians have minimized herpes — it’s not important, people don’t die from it, et cetera,” Dr. Leone said. “They don’t acknowledge that emotionally, it’s traumatic.”

“I think your type of story is one happening a lot more than we care to admit,” said Peter Leone, MD, professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and medical director of North Carolina HIV/STD Prevention and Control Branch. (He’s also served as a herpes expert for the New York Times). Dr. Leone hears stories like mine all the time, he said; last year, he got a call from a woman in Kuwait, whose gynecologist had told her she had herpes. “She was told that her life, in terms of anyone wanting her, was over,” he said. The woman phoned Dr. Leone out of the blue, pleading for his advice. He recommended a blood test. It came back negative: she didn’t have herpes.

“If you go in and the clinician tells you you have herpes, you damn well better make sure that visual diagnosis is correct,” Dr. Leone said. “Because it may not be.”

Part of what’s happened, Dr. Leone said, is that HIV sucked all the oxygen out of the room when it came to STDs. “People and clinicians have minimized herpes — it’s not important, people don’t die from it, et cetera. They don’t acknowledge that emotionally, it’s traumatic.”

Follow me down the herpetic rabbit hole, which is muddied first by stigma and second by the fact that, biologically, the herpes infection is rather complicated. The other expert I spoke with, H. Hunter Handsfield, MD, is Professor Emeritus of Medicine at the University of Washington Center for AIDS and STD. It’s one of the hardest STDs to teach to medical students, he said, and he dedicates more time lecturing about it than almost any other infection. “It is complex for a lot of doctors out there,” he said. “A lot of practitioners don’t have the level of nuance.”

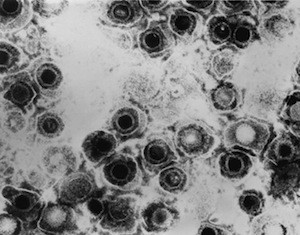

As you might already know, herpes is actually two different viruses: HSV-1 and HSV-2. They’re not site-specific and can occur interchangeably on mouth or genitals, the most popular manifestations being oral HSV-1, genital HSV-1, or genital HSV-2. Here’s herpes by the numbers: up to 50–60 percent of the population has HSV-1. The vast majority of those are oral infections — think cold sores, for those with symptoms — and probably under 10 percent are genital infections.

HSV-2 is almost always genital, which makes things much more simple. (People rarely contract HSV-2 on their lips, but of those who do, nearly all also have it genitally.) HSV-2 affects about 17 percent of adults, but here’s the scary part: 85 percent of those infected don’t know they have it.

The type matters tremendously, both experts told me. About 40 percent of people with an initial HSV-1 outbreak will never have another. The rest will get one or two outbreaks over the next couple years, Dr. Handsfield said — and then usually nothing after that.

Those with HSV-2 have it much worse. Of those people who acquire HSV-2 and whose initial infection causes symptoms, they’ll have an average of four to eight outbreaks a year for the next several years. “It’s very different than HSV-1, which is something that people really need to know and want to know ahead of time,” Dr. Handsfield said. “If you’re unlucky enough to have herpes, but it turns out to be HSV-1, you can say, well, I’m in a nicer category.”

But shedding — when the virus surfaces to the skin and can be transmitted to someone else in the absence of symptoms — is the real reason everyone is terrified of herpes. Thanks to asymptomatic viral shedding, you can get it when skin looks perfectly normal. It’s the reason doctors like mine urge disclosure before every sex act.

“With HSV-2, you not only have frequent symptomatic outbreaks, but you have high rates of the virus being present in the absence of symptoms,” Dr. Handsfield said. In fact, 70 percent of HSV-2 transmissions happen without symptoms, since people with HSV-2 shed practically all the time, said Dr. Leone.

As for HSV-1, anyone who’s ever had a cold sore sheds from the mouth 13–18 percent of the time, Dr. Leone said. And what of the folks infected with HSV-1 genitally? How often do they shed?

“It appears that genital-to-genital HSV-1 transmission is rare,” Dr. Handsfield said. So rare, in fact, that neither of the two doctors had ever seen a case: to their knowledge, not a single one of their patients has ever spread a genital HSV-1 infection to someone else’s genitals.

Let’s get this straight: HSV-2 and oral HSV-1 both shed fairly frequently, while genital HSV-1 appears to shed rarely, if at all. So who should really be disclosing?

Doctors, including these two experts, strongly agree that people with genital HSV-2 should always disclose, since they’re likely to pass along the infection without symptoms.

As for genital HSV-1? That’s less solid ground, because there’s no precise data and it hasn’t been formally studied, Dr. Handsfield said.

“You cannot find consensus on this,” Dr. Leone said. “You won’t find clear recommendations.

“I’ll be honest with you,” he continued, “I even question whether or not you need to disclose that you have genital HSV-1 to someone. If you’re not having an outbreak [of genital HSV-1], you’re probably not shedding, and you’re not going to be transmitting it to somebody else. And we don’t think that genital-to-genital transmissions are very common, so why are we telling folks to disclose? You may feel obligated and think that ethically, it’s something you should do. I would encourage you to do it if you feel that way. But from a biological standpoint, I’m not really sure we can make any recommendations around your need to disclose.”

Dr. Handsfield seems to agree. As long as I use protection, Dr. Handsfield told me, “I think you can make a perfectly valid ethical argument that there’s no need for disclosure because the risk of transmission, even if you’re infected, is very, very low.”

That leaves oral HSV-1. “I think people who have a history of cold sores should be disclosing before they perform oral sex on someone, because that’s where the transmission occurs,” Dr. Leone said.

This all came as a huge shock to me. All these years, I’d been disclosing a hypothetical risk, one neither expert had ever seen in their decades of practice. After every promising third date, I’d spend hours readying myself for my herpes speech, sometimes just to be politely kicked out once I gave it. Yet how many people who’ve gotten a couple of cold sores out there tell all their new partners, “I have herpes”?

“It makes no sense,” said Dr. Leone. “The people who are really transmitting are the ones who are sort of getting away with not disclosing.”

Of course, this is all a lot more nuanced than anything you’ll hear from a gyno visit. Genital herpes is so stigmatized that the facts are secondary to the myth.

Both experts want that to change. They’re part of the expert opinion symposium that helps revise the CDC treatment and counseling guidelines for STDs every four years. (Dr. Handsfield has been one of the experts since the CDC started the symposium in the mid 1980s.) This year, Dr. Leone sat on the herpes panel. Though he admits his opinion is a little further out on the fringe than the rest of the group, he said that this year, they added a section on HSV-1 that distinguishes it from HSV-2 and stresses the need for accurate diagnosis. “When the STD treatment guidelines come out [in 2014], they won’t be treating HSV-2 and HSV-1 the same way,” Dr. Leone said.

Genital herpes is so stigmatized that the facts are secondary to the myth.

Right now, a visual diagnosis — no tests, just a “you have herpes” — is the standard route for practitioners to diagnose a herpes outbreak. The CDC endorses “visual inspection” as a valid form of diagnosis on their website. Somewhere between 60–85 percent of the time, clinicians make a correct visual diagnosis, Dr. Leone said, but that leaves a pretty big possibility that it’s something else. Patients and their doctors can confuse irritated genital symptoms like herpes, yeast infections, and allergic reactions to vaginal hygiene products, Dr. Handsfield said.

Most people wouldn’t want to take a 20 percent chance that they’ve wrongly diagnosed a lifelong disease. So why wouldn’t doctors just conduct a simple test?

“They’re lazy, they’re ignorant, and they don’t like talking about sex,” Dr. Leone said. That reticence is especially alarming when it comes to oral sex, since more people are getting herpes through head than ever. “We’ve seen a decline in the number of kids growing up who acquire herpes labialis (of the mouth) in childhood,” Dr. Leone explained. Because these kids lack HSV antibodies, more and more are acquiring HSV-1 through oral sex in adolescence and early adulthood — and yet nobody talks about it. “That’s why I don’t necessarily hate to hear Michael Douglas talk about his cunnilingus in a macho, championship way,” he said. “It is good that there’s someone now who is bringing up oral sex in the general population dialogue, because we don’t discuss it.”

Including gynecologists. Dr. Leone said he’s heard clinicians give all kinds of excuses for not testing patients for herpes, mostly along the lines of why find out, when there’s nothing my patient can do about it? “You sort of have a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy around herpes,” Dr. Leone said.

Maybe because lots of doctors don’t want to deal with herpes, they sometimes miss the only opportunity to nail it definitively: during the first outbreak. The gold-standard for diagnosing herpes is called a PCR — polymerase chain reaction — a test that looks for the virus in the sore, Dr. Handsfield said. After that, it can get really fuzzy (especially if you stop having outbreaks.)

Blood tests are the next best, but they’re far from perfect. If you have HSV-2, they’re great — a blood test will only miss about one percent of people with the infection. But HSV-1 blood tests are far less reliable. For starters, many people test positive for HSV-1, since the test isn’t site-specific. Of those who test negative (like I did) 10–15 percent are actually false negatives, which means that the results could say you’re not infected when you are. (As my gynecologist suggested, antibody levels are sometimes undetectable.) By comparison, syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B have almost no false negatives, Dr. Handsfield said. HSV-1 has probably the highest false-negative rate.

I could safely rule out HSV-2, since my blood test was negative and I didn’t get recurrent outbreaks. But I could still be one of those 10–15 percent with invisible HSV-1.

If so, I’d have to try pretty hard for a positive diagnosis. The only sure way to tell is to wait for another outbreak (chances are, one won’t ever come) and have the lesion tested then. Or I could special-order a more sensitive herpes blood test called the Western blot, which is analyzed almost exclusively at the University of Washington. And if that comes back negative, the herpes-free diagnosis still isn’t 100 percent.

What’s a girl to do, with no recurrences, a negative blood test, and this infuriating margin of error?

Neither doctor could diagnose me as having or not having HSV-1 over the phone. “At this juncture, if I were a betting man and going to Las Vegas, I would have to go right on the simple bets, red versus black, 50–50 either way,” said Dr. Handsfield. But Dr. Leone wagered that it wasn’t herpes or any STD, judging by my extremely quick onset of symptoms and pair of negative blood tests. Even if the blood test was wrong and I did have it, I almost certainly wasn’t putting anyone at risk.

“Just move on with your life,” Dr. Leone said at last. “You don’t need to disclose anything to anyone. And try not to get herpes.”

I thought I’d never have another herpes conversation after being cleared. Recently, I met someone — a doctor, of all professions — and was so relieved not to have to tell him. But something strange happened about a month into dating and sex: I wanted to tell him. Not as a confession or a caveat, but as a path to pair-bonding. I wanted to share this deeply personal thing with him, this part of me that’s informed my experience with love and sex and intimacy. So I made one final disclosure.

“Wow,” he said after my long, over-complicated speech. “I like how your first instinct is to call up the world’s leading herpes experts.” That was it. Then he held me, kissed me, and slipped with me under the sheets for some truly perfect sex.

•••

“There’s a lot of bullshit out there on the web,” Dr. Handsfield told me, but for those seeking accurate herpes info, he recommends these sites:

American Sexual Health Association, a non-profit agency for sexual health information with a particular historical interest for herpes (Dr. Handsfield is on the board of directors).

Westover Heights Clinic, a private STD clinic in Oregon with incredibly thorough herpes information, counseling, and even disclosure tips.

•••

Photo via senoranderson/flickr.

Previously: The Perks of Herpes