Ask a Jeweler: A Beginner’s Guide to Pearls

by Anna Rasche

I’ve gotten a number of questions about pearls lately, so I put together a primer of sorts. Send me your questions here!

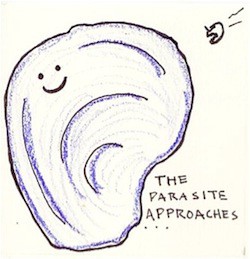

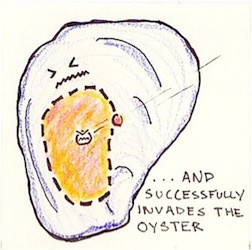

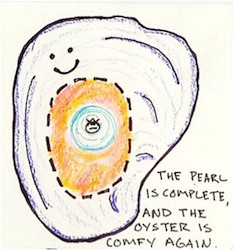

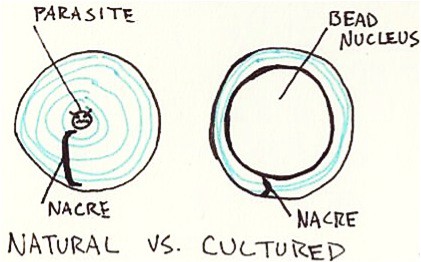

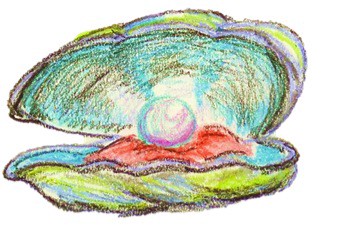

Natural pearls form when a parasite burrows into an oyster or mussel. The mollusk, trying to make itself more comfortable, coats the parasite with layers and layers of the same shiny, smooth, comfy material that covers the inside of its shell. This material, called “nacre,” is produced in the mollusk’s mantle tissue. When the mantle deposits enough layers of nacre around the parasite a little clump forms, and voila — you have a pearl!

Because a relatively small percentage of wild mollusks ever need to make a pearl, for most of history they were very rare and very expensive. Like, more expensive than diamonds. Millions of oysters and mussels — from the rivers of Scotland to the Indian Ocean to the Caribbean sea — were cracked open so that the nobility of Europe and Asia could cover themselves in pearls from head to toe. Pearl divers, often an enslaved or marginalized group of people, were forced to swim down to depths of 80 feet and haul bags of oysters back to the surface.

“Indians Diving for Pearls” by Jan Collaer

Sometimes the oysters were opened right on the boat. Other times the piles of unopened shellfish were left, carefully guarded, to rot on the docks. Once flies had removed all the flesh, workers dug through the shell piles in search of treasure. Finding even one pearl was a rare occurrence. Finding enough pearls of the same size, shape and color to make a whole necklace was a task that could take years. Throughout history, many kingdoms had sumptuary laws in place to make sure that the best pearls were only worn by the fanciest of fancy people.

Queen Elizabeth I by George Gower

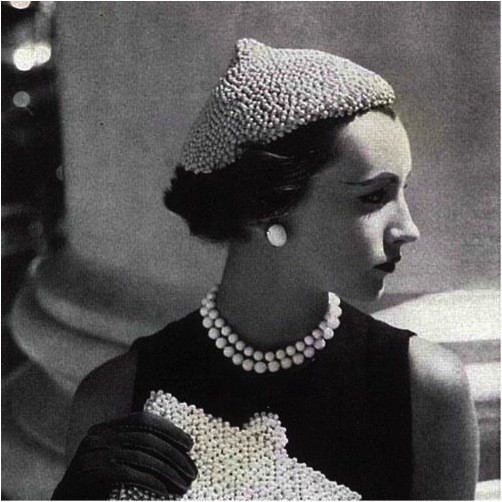

Gilded-age American heiresses took their fashion cues from Old World royalty, and draped themselves in obscene amounts of pearls. Seen as a symbol of innocence and the ever-important virginity, pearl jewelry was the ultimate bridal gift.

At the start of the 20th century, although technically no longer restricted to the upper-classes, the cost and rarity of pearls meant they were still a very exclusive gemstone. All this changed, thanks to this guy:

Drawing upon centuries of the trials and errors of other aspiring pearl cultivators, several Japanese gentlemen perfected the art of farming oysters to produce pearls. Kokichi Mikimoto was one of these men, and by purchasing the rights to methods developed by others, Mikimoto secured his place in history as the father of the farmed (or “cultured”) pearl industry.

Cultured pearls differ from natural pearls only in that the irritant around which a pearl forms is purposely inserted into the mollusk, not placed there accidentally by nature. A technician sticks a tiny piece of pearl-producing mantle tissue from a donor mollusk onto a shell bead, and then gently inserts the bead into the host mollusk to act as a nucleus. The oyster/mussel then gets to go back and live in the water for a few years, coating the bead with nacre just as it would a parasite. The size and shape of the nucleus determines the size and shape of the resultant pearl.

Starting in 1921, massive crops of high-quality cultured pearls grown in Japanese Akoya oysters hit the world market. People promptly freaked out. Not only were these cultured pearls indistinguishable from natural pearls, but they were a fraction of the cost. OG natural pearl dealers wasted no time in banding together to slander Mikimoto’s pearls as inferior imitations of the real thing. Poor Kokichi even had to stand trial in France against accusations of fraud. Luckily, prominent naturalists backed up his claim that cultured pearls form in exactly the same manner as natural pearls.

Pearl prices plummeted all over the world as perfectly round, cultured, Akoyas flooded into jewelry shops. For the first time in history genuine pearl strands were within the reach of every housewife and working girl.

The success of Japanese oyster farms made natural pearl diving operations obsolete, and the centuries-old industry dried up completely within two decades. Today, any pearl for sale is assumed cultured unless a gemological laboratory has examined it and stated otherwise. Fine strands of natural pearls do still show up at estate sales and auctions, and are much sought after by jewelry collectors. Because of their rarity, natural pearl necklaces consistently fetch prices well above their cultured counterparts.

Now, since different types of mollusks all produce different looking pearls, there are many varieties of cultured pearls on the market. The major varieties:

Akoya: Japanese Akoya oysters were the mollusk of choice for Mikimoto, and continue to produce the classic white, round, lustrous pearls the company is still known for today.

Freshwater: Mostly grown in China, these pearls come in a variety of colors and can be cultured around just a piece of mantle tissue, no bead nucleus required! Unlike other varieties of cultured pearls, it’s possible to grow multiple pearls simultaneously inside one host mussel. Because of this, they are affordable and abundant.

Tahitian: A bit larger than Akoya pearls, they are often a beautiful “black” color.

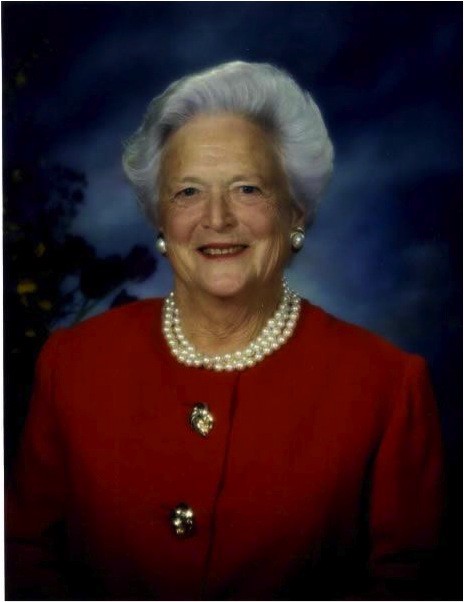

South Sea: Giant pearls grown in the giant pinctada maxima oyster. They come in different colors, and are favored by very rich old ladies. Shout out to Barbara Bush.

The quality of all these pearl varieties can be affected by things like pollution, water temperature and disease, so today the industry uses seven factors to assess (and assign monetary value) to different qualities of pearls. These factors are Size, Shape, Luster, Color, Surface, Nacre Quality, and Matching. If you ever consider dropping some serious cash on pearls, these factors are important to understand.

Size: All other factors being equal, a bigger pearl is more valuable. The size of the pearl is limited by the size of the mollusk it grows in.

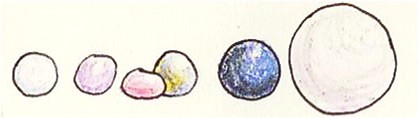

Shape: Pearl shapes are divided into three categories and seven main shapes. In order from most to least expensive:

Spherical (Round, Semi-Round):

Symmetrical (Oval, Button, Drop):

Baroque (Semi-Baroque, Baroque):

Circled:

Sometimes, for mystery reasons, pearls grow with a bunch of concentric ridges around them, so each of the preceding shapes can be either circled or non-circled.

Color: Pearls color is determined by the color of the Mother of Pearl (aka nacre) of the host mollusk. (In addition to the basic hue, a lot of pearls have a second, more subtle translucent color called an overtone. Ex: a white pearl may have a pink overtone. If a pearl has more than one overtone color present, you can say that pearl has orient.)

Luster: Luster is how shiny a pearl is. The shinier, the better. You want to be able to see your reflection all up in there.

Surface: Most pearls will have little bumps or blemishes on them. The less noticeable the blemishes, the more valuable the pearl.

Nacre Quality: This is basically quantifying how good a job the oyster did in covering up it’s pearl nucleus. If the pearl is shiny and you can’t see the bead nucleus through the nacre, than the nacre is considered an acceptable thickness. If you can see the nucleus, or the pearl has a ‘chalky” appearance, that is some crappy nacre. Poor nacre quality is often the result of harvesting a pearl too early.

Matching: This factor only applies to strings of pearls that are supposed to match each other. The more uniform the pearls, the more expensive the necklace. Single pearls or funky, purposely mismatched designs are exempt.

Of course, pearls are often dyed, bleached, polished etc. to improve perceived quality, so if you see a real swank looking strand for next to nothing it’s probably been “enhanced” in some way. This is all fine, as long as any treatment is disclosed and the pearls are priced appropriately. As with all fine jewelry, if you want a real, quality piece, it’s better to spend a little more at a reputable company than try to save a few bucks by buying from a dubious internet dude.

If you want to find out if a pearl is even real (i.e., grown in a mollusk, and not glass or plastic), the classic “tooth test” is really the best way. If you gently rub a pearl against the edge of your tooth, a real pearl will feel gritty and a fake pearl will feel smooth.

Because if the world is your oyster, you better know how to find the pearl.

Previously: Ask a Jeweler: Shady Platinum, Sizing Up Your Rings, and the Case For Sapphires

Anna Rasche is a trained gemologist who works in the diamond district by day, and helps run The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies by night. Ask her anything.