When Mimi Got Old

by Maddie Esposito

Mimi was the kind of grandma who always said the current year was her last. “72! I never thought I’d make it to 72. I won’t be around for 73, but boy, it sure is great to be 72.” The “boy” in that sentence isn’t affectation. That’s actually how she talked. Her husband, my papa, died two days after my third Christmas. I don’t remember anything about him.

I remember her 80th birthday party at the St. Louis Club. I remember her dancing to Maria Muldaur.

I don’t remember the last words I said to her before she was admitted.

It was late October, the first day of a week-long RV tour, our second-to-the-last of the campaign. I remember what I was reading (Runaway by Alice Munro) and what I was wearing (polka dot blouse, jeans, brown boots). I remember where we were going (Festus to Ironton to Eminence to Mountain Grove to Springfield). I remember what I had for lunch (jalapeño poppers and a hush puppy).

I remember I didn’t have dinner. I was at a bar with two campaign staffers, watching the Cards lose to the Giants, waiting on the third to pick us up so we could get food and possibly meet up with the fourth to drink alcoholic slushies. He texted that he was in front. I walked out alone while the stragglers paid their tab. I remember opening the door to the Ford Flex, how unsettled he looked telling me, how unfair it seemed that he was tasked with doing so.

We picked up my mom from her hotel and drove five hours, from the south to the east, on a mostly empty highway. She slept in the back. I remember wishing I hadn’t drank two whiskey sodas. I remember listening to XM radio. I don’t remember what was playing.

I remember the last words Mimi said to me, lying in her hospital bed, fully awake for the final time. “What am I going to do?” she asked, her dilated eyes ping-ponging between me and my cousin. “You have to tell me what to do.”

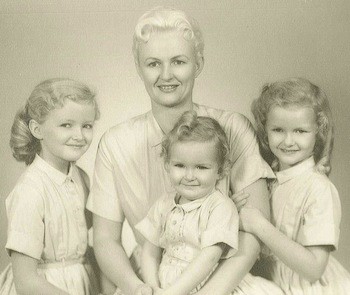

She was in poor health the majority of her adult life — overweight, arthritis, diabetes. My siblings, cousins, and I were kids when she had both of her knees replaced. She let us drink Diet Cokes, the caffeine bringing out our inner sociopaths. “Mimi, watch,” we’d yell before dropping to our knees in one movement, her single-story, Ranch-style house shaking with the impact. “Oy, my bones!” she’d howl. She’d laugh and we’d laugh and we’d do it again. I remember eating butterscotch candies. I don’t remember what brand.

Four days after entering the ICU, she was discharged to the ACE. I remember learning that ACE stood for Acute Care for the Elderly. I remember thinking the only place more depressing than the ICU is the ACE.

I remember taking her home for hospice care at the end of the week.

Watching someone die is a much different experience than being told someone has died. When my mother told me my father was killed, six years earlier, I had a visceral reaction. Tears fell instinctively. I remember saying out loud, “I’ll never smile again,” which has to be one of the stupidest things anyone has ever said. Even stupider is that I believed it. When Mimi let out her last breath, her lips puckering like a fish after the air was let out, I don’t remember crying.

I remember my aunt making us take a shot of Skyy vodka, Mimi’s drink of choice. I remember walking to the grocery store on an otherwise perfect autumn afternoon. I don’t remember what we bought.

I remember the transition Mimi made after her brother died, a year before her, in the same room in my mother’s house. She was no longer Mimi but Generic Old Person. Her sentences trailed off. Her hands were more shaky; her legs less steady. Her free time, which was all of her time, was spent in a chair half-watching Pawn Stars, Storage Wars, or whatever happened to be on the Game Show Network. Her belly didn’t shake when she laughed.

On the campaign trail, people would ask me how she was doing. “Oh, she’s good. She’s fine. She’s just old, you know?” I remember thinking I never wanted to be described that way. I’m comforted that she no longer has to be.

Maddie Esposito lives in New York but misses Missouri. Her mother is U.S. Senator Claire McCaskill.