Welcome to Stoner’s Laundry

by Mary Margaret Alvarado

Stoner’s Coin Op Laundry is on the corner of Wahsatch Avenue and St. Vrain Street in downtown Colorado Springs. The white stucco building was built in 1904 and was, until 1958, the Ideal Grocery & Market; city directories note that it was vacant the following year. In 1960 it appears as Roy C. & Mrs. Betty Mason’s Econo Wash Self Serve, on a line next to entries that indicate that this woman is the “wid” of “Chas Wm,” and that this man is a “linemn” for the “Tel Co.” The 1975 directory has it under the surname “Stoner.” Some patrons swear it is a laundromat for stoners, and a banner of “Cannabis” graffiti is still legible under layers of mismatched white paint.

1975 was a prosperous year for the Stoner family; they had four “speed queen” laundries and a trophy room and taxidermy shop. Those are gone now, but their original Laundromat is still in business, though the word “original” has almost faded from the hand-lettered sign. It is open every day, from 7 A.M. until 9 P.M. In the daytime, the building’s southern face is a gallery for branch shadows; in the evening, its western windows are a tableau by Hopper, in a scene made for Christenberry. At night, Stoner’s looks like a lantern.

This is our deaf neighbor Lloyd and his dog, Little Bit. For five years we’ve lived three houses down from Stoner’s, and across the street from Lloyd, his sister Wanda, and her husband Dave. Dave drives a decrepit minivan around town, the back window of which declares, “IF YOUR PASSING ME, YOUR SPEEDING.”

When we get to our street my three-year-old daughter says, “There’s Stoner’s Laundry” to indicate that she’s home. I took these photos in the late winter and spring of 2013, ducking out of evening dishes and bath time for the baby and running down the block with my dinky Panasonic DMC-Z56, which I didn’t really know how to use. I told my daughter I was going to “my studio.”

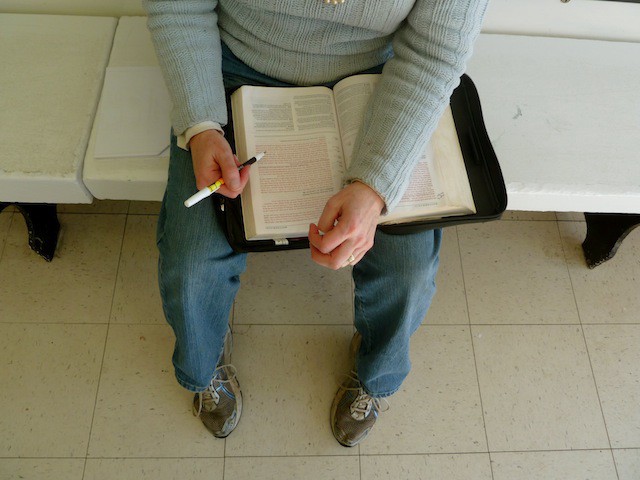

There is nothing to do at Stoner’s laundry. There are no TVs, no radios, no magazines. There is one soda machine, and a rack for Thrifty Nickles that is usually empty. I’ve seen few so-called smart phones in the place. You can sit in a plastic chair, or you can sit in a metal chair. People talk, and some hold court for hours; they fold clothes; they head outside to smoke. At some point someone crawled under one of the three folding tables and drew intricate, skillful studies of a pinecone, a bird, and a tree by water. This woman drives over on Sunday nights in an Econovan with other people from her storefront downtown church. Her bible has Jesus’ words in red.

Some people come because Stoner’s has “the hottest dryers in town.”

Others only like to come in the morning, when it’s quiet.

Often there are one or two homeless men at Stoner’s, especially when it’s cold. The man in the orange hat brings a radio with him and stands before it, talking. The man in the red coat had a bad stepfather in Michigan; he’s still trying to escape. I always ask people if I can take their photo; he said yes, but first he wanted to straighten his clothes.

One recently homeless man wrote a book of poems called I Lost My Pants. He travels with his two remaining possessions: a black plastic bag full of clothes, and his notebook. Over the poems he’s written down the addresses of possible homes.

Stoner’s feels like a public place. In the hours between when the doors are unlocked and locked again, it is an experiment in small-scale anarchy and communal property that works. The owner isn’t around, and neither are the cops. People sleep here. They kiss. They charge their phones and wash up. It is not unusual for the neighbors to bring food to strangers who say they have nothing to eat.

Children seem to like it here. There are poles and baskets and things to climb on and floors to slide down and interesting, spinning machines. The mothers and fathers aren’t up to much, and sometimes someone brings Funyuns or a ball.

This block was built up by people with tuberculosis, mostly black, who moved to Colorado Springs for the sanatoriums and the balm of high, dry air. Now the air smells like clean laundry. Most of the year, the doors of Stoner’s are propped open and the sky and the people stream in and out.

Mia Alvarado is the author of Hey Folly (Dos Madres). Her homage to her dumb phone appeared recently in The Point. She has work forthcoming in the Boston Review, Wag’s Revue, and Sojourners.