Take a Nice Selfie at My Funeral

by John Ganiard

“The face alone has launched a thousand think pieces. So now the question is not one of basic selfie-justification, but rather, why must a photo of my face be justified when a photo of my bookshelf is not?”

–Sarah Nicole Prickett

1.

I went to a Catholic parochial school. This means the things you expect it to mean. There was a crucifix in every room: a wall-length stone-cut crucifix in the entryway; in the gymnasium, high up, a crucifix that was enormous, but not quite to scale.

At my school, grades 7 through 12 dedicate a class to a certain facet of the Catholic faith. Junior year, that class is called Death & Dying, and the final project is planning your funeral. You charted the expenses, designed the program, wrote your own eulogies. Previous to this project, you would have taken a class trip to a funeral home, an experience that usually included looking at a dead body; a note from your parents was the only way to opt out.

Large portions of the class, toward the end of the second semester, devolved into discussions about the merits of even having the class at all. Our teacher grew frustrated. Clearly the purpose was that we confront death — our own, specifically. At the time I regaled my secular friends with stories from Death because it was easy; it distanced me from a thing I thought or thought I should think was silly. But I do remember having a tough time writing what my brother would say at my funeral, and giving a lot of thought to it. I do remember secretly taking it seriously. At the time I hadn’t been to a funeral in awhile; the memories had reduced themselves to images of crying, the knowledge that people I didn’t normally see crying would cry.

2.

Per “Dead” Ohlin, the original vocalist of second-wave Norwegian Black Metal band Mayhem, shot himself in the forehead with a shotgun on April 8th, 1991. Per’s body was discovered by Øystein “Euronymous” Aarseth, who instead of notifying police, first headed out to purchase a disposable camera. He then re-arranged elements of the scene and took photographs of Per’s body.

In 2005, former Mayhem bassist Jørn “Necrobutcher” Stubberud suggested to the Guardian’s Chris Campion that “Øystein was shocked by Dead’s suicide. And taking the photograph was the only way he could cope with it, like, ‘if I have to see this, then everybody else has to see it too.’” One of these photos somehow became the cover of the Mayhem bootleg album Dawn of the Black Hearts. The image is readily available online.

3.

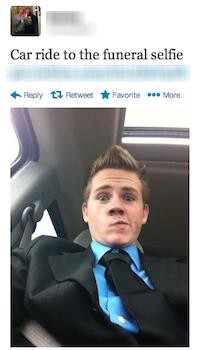

Selfiesatfunerals.tumblr.com was started by writer Jason Fiefer, currently an editor at Fast Company. Jason also created selfiesatseriousplaces.tumblr.com: a collection that he admits, and I agree, contains a “more egregious” kind of selfie. There is an uncanny, alien quality to sites of reverence in a few of the images (Holocaust memorials, former concentration camps) that is absent from any funeral scene. But what both Tumblrs have in common is the youth of their subjects.

Some notes about the contents of selfiesatfunerals.tumblr.com:

Total images extant: 21

Total images involving this face: 10

Two-finger gesture present: 2.5

Instagram photos: 9

Twitter photos: 12

Guess at general age range: 13–19 (12 possible lowest, 21 possible highest)

Scrutinizing the sample size for statistical meaning reveals almost nothing. Only one image — a boy making the kind of face you make when stifling inappropriate laughter — reveals the departed (in open casket). Were it not for hashtags likes #funeral, #rip, etc., you wouldn’t necessarily know the context of these selfies. They take place where we have come to expect them to take place: bathrooms, bedrooms, mostly places where mirrors are available; they seem to be taken preceding or proceeding the funeral. Except for one featuring a statue at “pop’s funeral” that is likely in the funeral home, and another one next to a framed picture of the deceased (one that I actually find, caption included, fairly compelling), none stand out as definitely-at-a-funeral. No one’s in pews at mass, no one’s right up next to an open casket, no thumbs-up by a church marquee, no outright desecration.

That is to say, the photos individually seem like one selfie in an otherwise unbroken stream of selfies, one selfie at a funeral amidst hundreds of selfies under countless other circumstances. What persists is the act and not the context of the act.

“My true, honest motivation here,” Jason notes, “is to convey the degree of surprise and head-shaking amusement that I felt when discovering these. Each Tumblr starts with a simple hypothesis: Are people posting photos of themselves doing X? Then I just search.” The discovery is then less where the selfie is happening than where it ever isn’t. The discovery is merely the degree to which the selfie is entrenched.

Jason adds: “In aggregate, I think they have a kind of cultural artifact quality. But I’m not the arbiter of good taste; it’s not like I’m declaring myself the social media referee. I’m just pointing out what’s out there.”

It is also in aggregate, and divorced from their unbroken stream, that we suffer the illusion of the “discrete, alarming phenomenon,” something worthy of Huffington Post headlines like “A Sign The Apocalypse Can’t Come Soon Enough,” something that will bait the outrage that drives pageviews. Within hours of the site’s creation, its images had been reposted by Gawker, Thought Catalog, Death and Taxes, etc. No further editorializing necessary.

4.

How many funerals have you been to? I have been to three. What is a common number of funerals to go to? The most recent one I went to was last month, at an Episcopalian church outside of Detroit that one side of my family frequented primarily when they were still all together. I knew that they were from this part of Michigan, raised Episcopalian. I have been to that town a hundred times, but I didn’t know about the church, didn’t ever consider that the “family church” must be around here.

Earlier in the week I had gone to the mall in Ann Arbor to buy a blazer and khakis because I owned neither. In the process of second-guessing the fit of a blazer I thought looked okay and was not too expensive — in the midst of just wanting to get this over with — I took pictures with my phone of myself in a column of mirrors at JC Penney. I texted one to my mother and one to a friend I thought might know about this kind of thing. My mom did not reply and my friend just said “Looks fine!” and I felt mildly dismissed.

I texted back that I knew that funeral shopping was a weird circumstance in which to take a selfie, but deep down I don’t know what separates shameful self-awareness from not thinking to feel shame.

Before the service, my brother and I sat on some couches at the back of the reception area, opposite the stairs leading down to it. As people started to come in and gather around the tables and chairs that had been set up, I became increasingly preoccupied with my phone, reading sports news. I am the average kind of shy, and more so around family members I’m not sure if I am supposed to remember, or remember me.

5.

Selfies are inherently vain. A funeral selfie is inherently an act of bad taste. A funeral is not about you, and should not be; a funeral is about the celebration of another person’s life, about the mourning of that person’s death. But inevitably, a funeral does make you think about yourself, about being alive and about being dead. A funeral makes you miss the person who has died, or reminds you of how you could have been closer to that person, or how you barely knew that person to begin with.

It is difficult to extricate these things. At the funeral I went to, I laughed at the part in the eulogy where the eulogist mentioned that the playing of bagpipes had been jokingly included in the arrangement of the living will. Then, I cried at the actual bagpipes that played in fulfillment of that joking wish. The bagpipes were also, in the small church, very loud, and I found that was also kind of funny. Funerals are emotionally confusing. I think I forgive a subset of teenagers for being unable to do anything other than what they may normally do. They pull faces and take pictures of themselves; they act as though they don’t care; they broadcast that they do care, or care facetiously, even if they don’t actually, even if they’re just being vain.

And, isn’t vanity a defense against death? And isn’t dismissing a selfie as purely “vain” also dismissing this form of nascent inquiry and self-preservation? In the New York Times, Jenna Wortham wrote, “Rather than dismissing the trend as a side effect of digital culture or a sad form of exhibitionism, maybe we’re better off seeing selfies for what they are at their best — a kind of visual diary, a way to mark our short existence and hold it up to others as proof that we were here. The rest, of course, is open to interpretation.”

The face you send out from a funeral is just your face again, and still, a reminder to others of our self’s current aliveness is — somehow, no matter the circumstances, and perhaps at a funeral, uniquely so — a denial of the inescapable, a refraction of the dark light of death. At the least it’s a way of saying, “If I have to see this, then everybody else has to see it too.”

Photos via josefnovak/Flickr, Selfies at Funerals.

John M. Ganiard is a bookseller who lives in Ann Arbor.