Susan Faludi on Facebook Feminism & the Danger of “Individual Women Empowering Themselves by…

Susan Faludi on Facebook Feminism & the Danger of “Individual Women Empowering Themselves by Deserting Other Women”

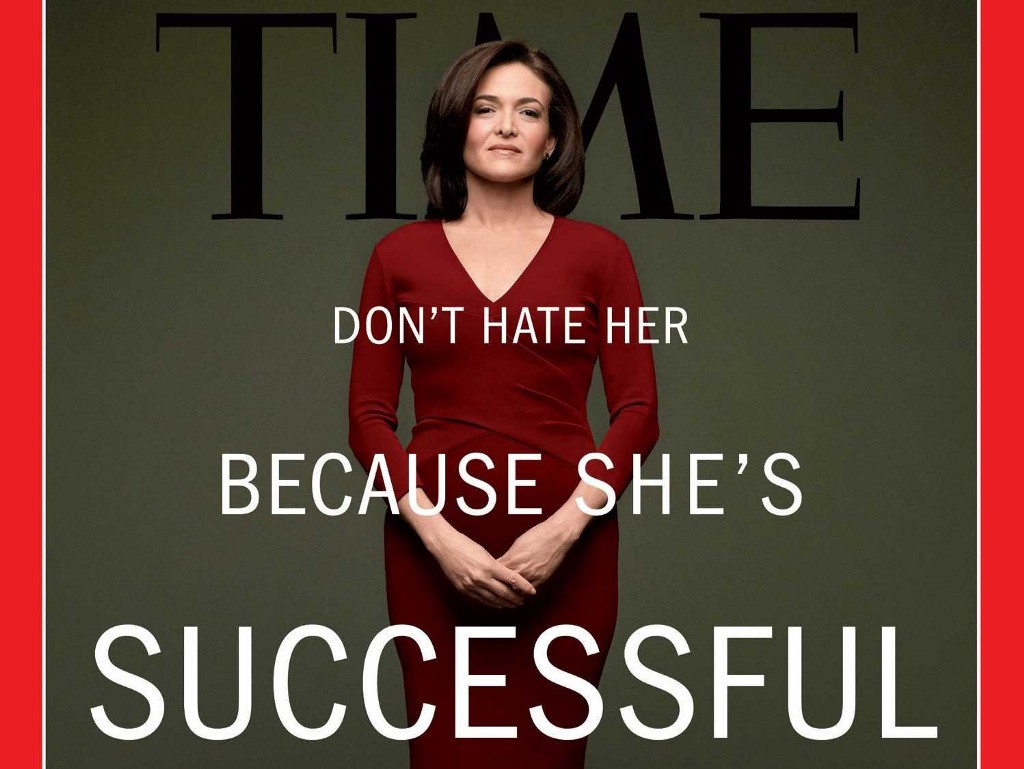

In case you missed this (I did), here’s Susan Faludi at the Baffler, eviscerating the 1%-friendly, free-market feminism of Lean In:

The clipped, jarring shift from the collective grievances of working women to the feel-good options open to credentialed, professional types is also a pronounced theme in Lean In, the book. In the opening pages, Sandberg acknowledges that “the vast majority of women are struggling to make ends meet,” but goes on to stress that “each subsequent chapter focuses on an adjustment or difference that we can make ourselves.” When asked in a radio interview in Boston about the external barriers women face, Sandberg agreed that women are held back “by discrimination and sexism and terrible public policy” and “we should reform all of that,” but then immediately suggested that the concentration on such reforms has been disproportionate, arguing that “the conversation can’t be only about that, and in a lot of ways the conversation on women is usually only about that.”

I’d argue that the conversation is actually never about policy reform, but anyway. Faludi then goes back to the radical “mill girls” of Lowell, M.A., who “turned out” in 1834 to protest wage cuts and labor conditions, and started a movement that, for a second, was intersectional; they got into the abolitionist movement, and mobilized across classes.

Cross-class female solidarity surfaced early in Lawrence, Massachusetts, after the horrific building collapse of the Pemberton Mills factory in 1860, which killed 145 workers, most of them women and children… Middle-class women in the region flocked to provide emergency relief and, radicalized by what they witnessed, went on to establish day nurseries, medical clinics and hospitals, and cooperative housing to serve the needs of working women.

But then, in the 1920s, the “ascendant consumer economy” began to offer an “ersatz version of emancipation, the fulfillment of individual, and aspirational, desire.”

Why mount a collective protest against the exploitations of the workplace when it was so much more gratifying — not to mention easier — to advance yourself (and only yourself) by shopping for “liberating” products that expressed your “individuality” and signaled your (seemingly) elevated class status?

Faludi makes the link between then and now neatly: “In the 1920s, male capitalists invoked feminism to advance their brands of corporate products,” she writes. “Nearly a century later, female marketers are invoking capitalism to advance their corporate brand of feminism.” The whole essay, like Nancy Fraser’s piece at the Guardian from last week, is a must-read.