Six Weeks Alone on the Camino de Santiago Pilgrim Trail

Victoria Golden is a 25-year-old Chicago resident. Over the summer, she spent six weeks alone, walking the Camino de Santiago trail in Spain.

How’d you get the idea to go on this trip originally?

I think it started in high school, when I read a play where one of the characters is a peregrina (pilgrim), and she stayed with a family in Spain, the way all the pilgrims used to on the Camino. And then I went to Spain in 2006 for a school trip, and I saw a book about the Camino in a store and read that, in 2010, the Feast of St. James would fall on a Sunday, making it an Año Santo Jacobeo, a holy year.

That was the year I was going to graduate from college, so that became my plan! 2010. But then that volcano erupted in Iceland, and there was no air travel between Europe and the US for a few weeks, and I had to cancel the whole trip. And I just saved the money and waited. This year was just the first time I could get that amount of time off work again.

Did you ever consider walking the trail with a buddy?

Not really — I always wanted to do it by myself, partly because I’ve never traveled alone by myself like that, partly because it felt like just a really personal interest.

Are you Catholic?

I was raised Catholic, but I’m not practicing now. These days most people on the trail aren’t doing it for religious or even religious-related reasons.

What do you pack for a six-week walk?

I packed super light — my bag only weighed 14 pounds. I took two sets of walking clothes and a dress, a guidebook, a journal and a pen, hiking shoes, Tevas, two pairs of socks and sock liners to prevent blisters, a sleeping bag liner and a travel towel. And toiletries. That was it! Just a backpack, carry-on size, so even my toiletries were three ounces or less — I figured I could buy shampoo and stuff there.

There’s so much information available about this trip online — lots of active forums, innumerable packing lists — that I felt that I knew what would be really important. Some of it I wouldn’t have expected, like a needle and lighter to pop blisters.

Damn. Is that what everyone did? Were you popping tons of blisters?

Yeah. I didn’t get blisters for a few days, but it was inevitable; my knees started hurting, my hip muscles started hurting, I ended up with a knee brace that I wore throughout the trip and lots of blisters. Everyone had them, and we talked about them all the time.

What was your travel route from the States?

I’d figured it would be smarter to get the cheapest ticket I could find to anywhere in Europe, and then get an intercontinental flight to Spain. So I flew into Stockholm and out of Oslo, and on my way to the Camino I went through Paris, and then to Bayonne, and then to a town called St. Jean-Pied-de-Port, which is a popular starting point for the trail. (You can start anywhere you want).

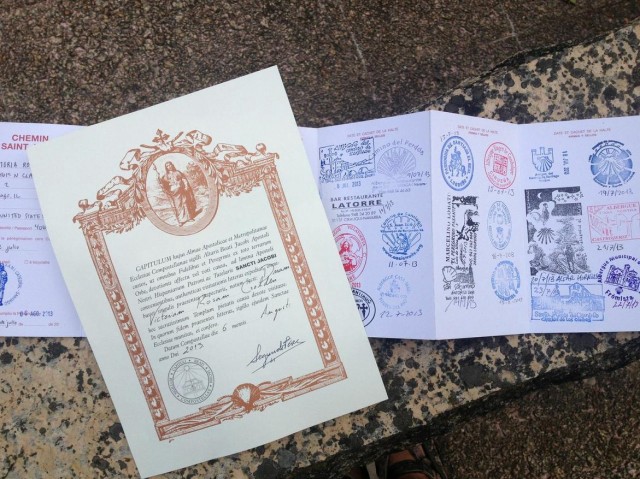

You end up with a compostela, a certificate that says that you’ve done the walk, and at the office in Santiago they record how many kilometers you’ve traveled: for me, it was 800. In Spain, actually, the compostela is something you put on your CV, so this is a really popular one-week vacation for people in country; they often start at a town that’s 105 kilometers away, just long enough for the certificate, and send their suitcases forward to every next stop. So it was a different experience over the last few days, and it was frustrating, a little bit.

But everyone had walked a different distance, and some people kept going after Santiago, all the way to the coast. I met people who’d been walking for a month longer than me, and one guy from the Netherlands had been walking from his front door, from March to August.

The people who’d been traveling for that long — how did they fit this into their life? Like that Netherlands guy, what did he do for a living?

He was retired, and he and his wife had planned to do the Camino together for years and years. And then she was diagnosed with cancer, and they couldn’t do it — and when she was dying, she told him she really wanted to do it by himself. He said it took him a long time to feel like he could.

Wow. Did you end up picking up a lot of these stories?

On and off. It was nice because you could have a lot of time to yourself, and then a lot of time for other people, and whatever you were feeling in the moment you could do. For the first three weeks I was mostly by myself; some days I’d walk a few hours with someone, and we’d show up at a hostel together and then leave together and then lose track of each other, and it was fine.

But what was really delightful was meeting someone again. After you see someone one time on the Camino, they’re your friend. So, when you’ve spent all day walking by yourself, and you get to a place where you can lie down and take a shower and see someone that you’ve talked to before, it’s the best feeling in the world.

I ended up with a group for about 10 days — I met them in a hostel, and ended up walking with them to the next town, and took a siesta, and just ended up staying with them for a while. I thought they’d all come together, but they were a group that had actually met the first day; two Korean guys, one my age and another in his mid-forties who didn’t speak English or Spanish, an English guy, a French woman, and other people like me who came in and out.

Do you speak Spanish? Did a lot of people on the trip?

I do, yeah. But the lingua franca was English — the Camino is really popular among Europeans and Koreans, and so if people spoke English, which many of them did, it was most often their second language, and Spanish maybe as their third.

It was an asset to speak Spanish, for sure. I’d majored in it in college, and considered myself pretty fluent, but I had never been immersed for so long. So I was practicing all the time, trying to talk to people, speaking as much Spanish as I could — and I think that shaped my experience in a positive way, especially when it came to logistics at the hostels, and meeting with a good reception from the hostel owners.

Were there lots of trail romances?

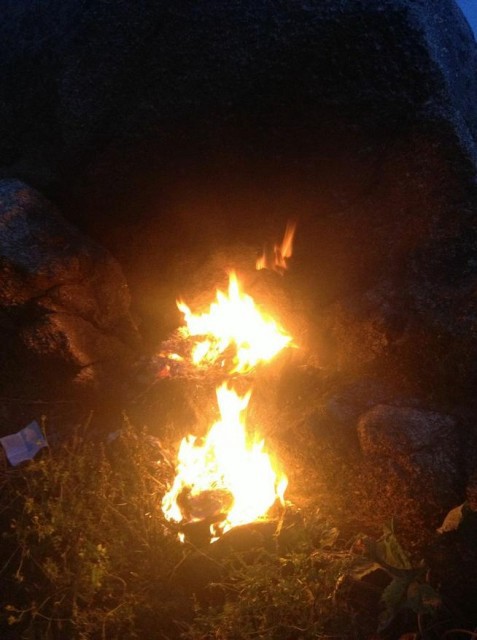

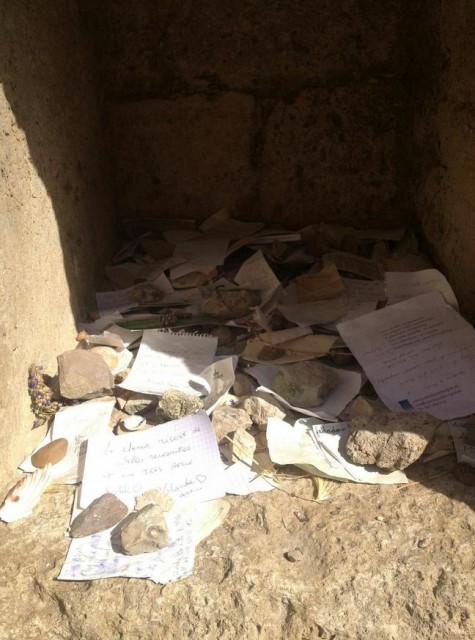

Oh yeah. And in a variety of ways. Some people had just met towards the end and were having budding romances, a lot of others were having a sort of “I really like him, but he doesn’t like me” experience, and on the last day of my trip I met a couple at the lighthouse, and we were sitting there together, burning our clothes, and it was a really wonderful moment — and this guy told me that he met the love of his life on the trail — and it was the girl he was with. I’d assumed they’d come there together, but they’d just met, and fallen in love. They were so excited about moving in together, so happy. It was really beautiful.

I think there’s something about an experience of this nature that makes people form bonds like that, right?

Yeah. A surprising number of people in my Peace Corps program married other volunteers that they’d just met.

Yeah, and I had that experience in terms of friendship for sure. Because, I didn’t have a big life event that spurred the trip — so many people had just quit their jobs, been fired, gotten divorced, gotten married. I was going just for adventure, to have fun — I did want to sort of “get away” from things, but not in the way that other people did, who would tell you up front that they were directionless or running away from something.

But still, I was freelance at the time, and all my stuff was in storage, and I’d finished my lease and was feeling pretty transient too, and it was really wonderful to meet people who were already in transient parts of their lives as well.

And so — you get sort of officially tracked throughout the journey, right?

Yeah. The Spanish government has built up a lot of infrastructure around the Camino. You start by getting a credencial, and every town you go through, the bars and restaurants and hostels each give you a stamp to prove that you actually walked that far. (And not everyone walks. People bike it, and I think 1% of people go on horseback — I saw one guy with a donkey, but that was it).

So I’d get stamps once or twice a day, and people make special stamps for their shops, and others set up booths on the side of the road and have pilgrim refreshments and a stamp. It’s really, really delightful.

And you stayed in hostels the whole time?

Yes. There are public albergues, and then private albergues that have to adhere to certain standards, but my favorite were the parochial ones attached to churches. They’d have community dinners where everyone would eat together and help clean up, and then you’d help set up breakfast in the morning, and they’d have a prayer service, and you paid whatever you felt was appropriate.

What time did you wake up?

5:30, 6 AM.

What did your day look like in terms of food?

So in the morning I’d walk for an hour or two, then stop and eat a pastry — a Napolitano, a croissant, or toast and jam — and have a café con leche. Then we’d stop for a second breakfast/first lunch around 9:30 or 10, and then at noon we’d stop and eat a sandwich at a bar — lots of ham and cheese — and have coffee.

For dinner, the hostel would have a pilgrim menu, or the restaurants in town would, and these were always set menus, like 8–12 euros for two courses plus bread plus dessert and wine or water. People got tired of eating these meals, because they were pretty similar: spaghetti, salad, garbanzo beans, pork with French fries, fish with French fries, French fries with everything. It’s pretty hard to be a vegetarian on this trip — once my friend got fish and it came layered with bacon on top. Dessert would be like a small pastry, or ice cream, or flan in some parts of the country.

Did you get sick of the food?

Yeah, but I’d go through waves — I’d think I’d never be able to eat another French fry and then a week later I’d be super into it. And everything tastes good after 15–20 miles. I didn’t lose a lot of weight but I think I did slim down over the trip, even though I was eating like 4,000 calories a day, just eating ice cream constantly. I never went a day without ice cream. It was so hot, it was all I wanted.

What was the average temperature?

High 80s, 90s. That’s part of why we tried to wake up so early — we tried to finish walking by 1 if it was hot that day, because often there was no shade, and it became really difficult to walk in the midday sun.

Did your schedule start to feel really natural? It sounds amazing.

Yeah. We’d go to sleep at 9:30 or 10 — the albergues had lights out around 10. And the whole time I was thinking, “This is awesome, I definitely want to do this when I get back,” and of course I didn’t. And of course, not everyone stuck to this schedule. There were party pilgrims, people who’d stay out all night drinking and sleep in the street till the hostel opened again. And we did go out in a few places, like when we were in bigger cities on weekends and could go to tapas bars and stay out till midnight.

It was also nice that we napped in the afternoon most days.

What advice would you give someone who was considering this trip?

I’d say definitely do it. Everyone should do it! And I’d say budget 30 euros a day, so like 40–45 dollars a day, plus your airfare. You can do the trip fairly cheaply if you want to. Some days I spent almost nothing, which made up for the other days that I had to pay for bigger expenses, like when I lost both my shirts.

How… did you lose your shirts?

[Laughs] A drying rack — I was getting my clothes early in the morning and must’ve just missed my shirt. And then another one I’d clipped to my backpack to dry, and it just fell off.

How much did you spend total?

Overall, about $2000. I did things really cheaply. I’m a big budget person and even though I’d saved for the trip I had to keep telling myself, “You saved this money, it’s okay to spend it.”

Did you get out of the trip what you wanted to get out of it?

You know, I wasn’t sure what I wanted out of it. I was rereading my journal from the trip earlier today and I saw that I’d written at the beginning, “I’m not expecting to have a big epiphany or to come back with this extreme sense of internal peace.” People had told me that this trip changes your life, that everything looks different afterwards, but beforehand I just kept thinking, “Well, I’m not going to the middle of nowhere. Wifi will still be widely available on this road.”

Then, over the course of the trip I was writing things like I wanted to be thankful for everything around me. I wanted to learn how to watch my thoughts, because I’d read that’s how you find enlightenment. I was rereading all of that this morning and laughing, because I think what I really got out of this trip was totally unexpected: being more open to people’s stories, feeling connections with them, recognizing that we were all connected by this act and common goal.

Because, the act of walking — in itself, it’s a beautiful thing to have in common with people, and it began to feel like a microcosm of the world. Everyone is on some sort of trip with themselves. In some way, everyone’s taking this trip together. So one of the things I’ve tried to do since the Camino is remember that — remember that everyone is going somewhere, and everyone’s got an interesting story. I tend to be a person who makes immediate judgments: if I like someone, I like them a lot, and if I don’t like them, I write them off. But now I think I’ve gotten better at seeing through the first thing that a person projects. The Camino really stripped people down, and me as well. So much of who you are is built by the people you’re around, the things and the places — and on the trip I was able to see, these are the parts of me that are always here.

Previously: me in Kyrgyzstan, many more from Edith.