“In 1958, a Connecticut court decided not to honor a ‘Ouija board will’ leaving $152,000 to a…

“In 1958, a Connecticut court decided not to honor a ‘Ouija board will’ leaving $152,000 to a bodiless spirit”

Smithsonian Mag has a superb long essay up on “The Strange and Mysterious History of the Ouija Board,” starting with the mid-19th century obsession with spiritualism, a craze with a distinctly Puritan flavor, that sort of Nathaniel Hawthorne thing:

Spiritualism worked for Americans: it was compatible with Christian dogma, meaning one could hold a séance on Saturday night and have no qualms about going to church the next day. It was an acceptable, even wholesome activity to contact spirits at séances, through automatic writing, or table turning parties, in which participants would place their hands on a small table and watch it begin shake and rattle, while they all declared that they weren’t moving it. […]As spiritualism had grown in American culture, so too did frustration with how long it took to get any meaningful message out of the spirits; calling out the alphabet and waiting for a knock at the right letter, for example, was deeply boring. After all, rapid communication with breathing humans at far distances was a possibility — the telegraph had been around for decades — why shouldn’t spirits be as easy to reach? People were desperate for methods of communication that would be quicker — and while several entrepreneurs realized that, it was the Kennard Novelty Company that really nailed it.

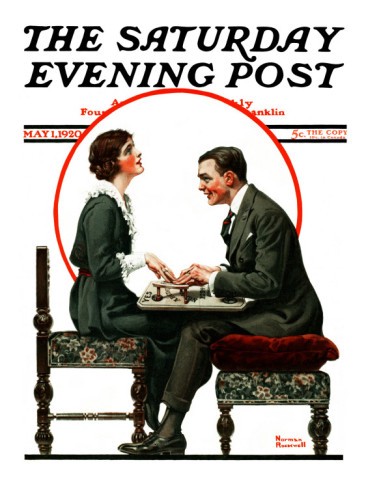

The boards grew enormously popular, especially in times of political uncertainty: the image here is a Norman Rockwell illustration from the ’20s, and one New York department store sold almost 50,000 in 5 months. As late as 1967, Ouija boards were outselling Monopoly. And people were literally going nuts:

In 1921, The New York Times reported that a Chicago woman being sent to a psychiatric hospital tried to explain to doctors that she wasn’t suffering from mania, but that Ouija spirits had told her to leave her mother’s dead body in the living room for 15 days before burying her in the backyard. In 1930, newspaper readers thrilled to accounts of two women in Buffalo, New York, who’d murdered another woman, supposedly on the encouragement of Ouija board messages. In 1941, a 23-year-old gas station attendant from New Jersey told The New York Times that he joined the Army because the Ouija board told him to. In 1958, a Connecticut court decided not to honor the “Ouija board will” of Mrs. Helen Dow Peck, who left only $1,000 to two former servants and an insane $152,000 to Mr. John Gale Forbes — a lucky, but bodiless spirit who’d contacted her via the Ouija board.

There’s so much more in this piece: James Merrill’s self-described Ouija-dictated poetry prizewinner The Changing Light at Sandover, the turning point (The Exorcist) that made Americans think the boards were evil, experiments on the ideomotor effect that necessitated Ouija-playing robots, the possibility of the Ouija board as a research tool to uncover more about our non-conscious thought processes. I’d like to see more Ouija boards in everyday life. “Who loves me,” I’ll ask it, and I’ll see the letters spell out B-U-R-R-I-T…