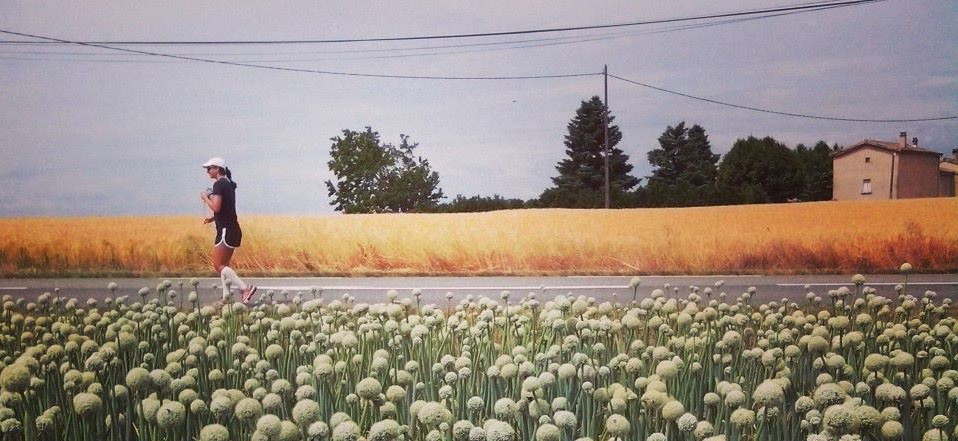

Interview with Zoë Romano, the First Person to Ever Run the Tour de France

by Melinda Misener

Yesterday, Diana Nyad swam 110 miles from Cuba to Florida; this summer, my elementary school classmate Zoë Romano ran the length of the Tour de France, a nine-week effort that followed her 119-day run across America in 2011. Zoë is the first woman to ever complete this cross-country route unassisted (she had no support vehicle trailing her, but pushed a running stroller with her belongings instead), as well as the first person to ever do the Tour de France route on foot. Over the last two years, she’s used her runs to raise hundreds of thousands of dollars for the Boys and Girls Clubs of America and the World Pediatric Project, and also: she ran the last ninety miles of the Tour in a single day. How was your Labor Day weekend?

Zoë spoke to me from her home in Richmond.

What made you decide to run cross-country in the first place?

I was already running a lot, every day, and I thought if I could do something where I was outside all the time, just moving on my own two feet and under my own power, then that would be complete happiness for me. I ruminated about that for a week, and then I started talking to a couple friends about it. One of them knew of someone who had just run across the country. When I heard that someone had done it, and survived, and loved it, I thought: well, if he can do it then I can do it.

How many miles were you averaging per day across the US?

When I started it was about twenty-five miles a day, but when I finished it was closer to thirty-five.

What did you carry with you while you were doing this?

People always asked, about my stroller, “Is there a baby in that thing?” No baby: I carried clothes for all weather, camping gear (tent, sleeping bag, water filter), safety stuff (pepper spray, compass, dog treats, first aid kid, etc), a phone and an mp3 player, stuff for stroller maintenance, a journal, a couple books, a camera, and then miscellaneous stuff like a clothesline, ankle braces, maps, an air horn, a Nalgene, energy bars, food, flashlight. But I ended up ditching stuff along the way, like camping gear I didn’t need because I was staying with hosts so often. I also ditched a lot of clothes I didn’t need.

And what did you bring for your Tour run?

I brought a lot of the same stuff, but this time I had a better idea of what I needed for clothes. Overall I didn’t have to be as careful this time with how I packed because Alex, my close friend who was filming a documentary, was following me in a van. Of course, Alex packed tons of camera gear.

How did you pick the Tour for your second big run?

I wanted whatever I did next to be a worthy follow-up to the US run. I didn’t want to do the same thing, but I didn’t want to do something easier. The Tour de France is known as one of the world’s most grueling events, so even though I was terrified of doing it, I was like, okay, I’ll try.

You wrote on your blog that running the Tour was “more athletic and more demanding” than running across the US. Tell me more about that?

The Tour organizers have had 100 years to make it as difficult as possible! If there was a mountain nearby, then the Tour route went over it. There were times it went up the same mountain two days in a row. If there were two routes around the back of a mountain, we always went the longer way.

So that was physically very difficult. I couldn’t train for the Alps in Virginia, because the elevation and the altitude weren’t comparable. And looking at the graphs and charts and maps and seeing that it could be much easier if it went this way, but we had to go that way — that was much more mentally frustrating than the physical frustration of actually doing it.

Do people often tell you that running like this is going to ruin your knees/hips/back/health?

Yeah, they have. The week before I left [for France] I was really nervous because I had new pain in my foot I’d never had before. I had, like, five doctor’s appointments and saw two different chiropractors and a podiatrist. The chiropractors — who were sports chiropractors — told me they supported my decision to try to run, but the podiatrist told me it was the stupidest thing I could do, that I was going to come back broken.

What happened with that as you started running the Tour?

I took a week off before I left, and it never gave me any problems after that. It was tendon pain that felt like a stress fracture.

What have you learned about the nature of injury?

I think I learned that injuries aren’t fully out of your control, and they’re also not fully in your control. If you can to be really attuned to your body, and understand what’s significant pain and what’s not, your body can do its thing and you can manipulate it in the right way and help with injury prevention. That wasn’t something I understood well before, when I just stretched and hoped everything would go well.

Has all this running brought on any significant physical changes?

I felt like I was taller after my cross-country run, and everyone in my family was like, “You’re taller,” and then we measured my height and it was true: I was a full inch and a half taller. It’s funny how everyone told me, “Oh, my God, you’re going to kill your body.” But when I finished I was like, “I grew!” If that isn’t the sign of a healthy body…

What about after running the Tour?

I swear I got taller again. I haven’t measured myself yet, but everyone in my family keeps saying the same thing.

What are some common misconceptions about what it’s like to run thirty miles a day?

A lot of people expect that if you run this much, you come back and you’ve lost, like, 100 pounds. But they don’t take into account that I was in training for this, in shape for this, before I left.

What are your eating habits like for these long runs?

For the first couple of weeks, I’m ravenously hungry all the time. But then my body adjusts. By the end of both runs, I was eating more or less like I normally do. People would assume I needed to eat 7,000 calories a day, but I didn’t.

I drink coffee in the morning. I eat a lot of fresh fruit. In France we were being really budget conscious; a lot of nights we had bread and cheese and tuna because that’s what we could afford at the grocery store.

Both times you’ve done these big runs, it’s been to raise money for charitable organizations. Do you think you’d be doing runs like this if they weren’t for the purpose of raising money?

I’d love to do these things regardless, but when I’m able to make it about more than the run, it’s really motivating. I think if you can take what you do in life and turn it towards greater purpose, it inspires you when you don’t feel like doing whatever it is you decided to do.

Also, working with charities has helped me stay in touch with so many good people. If I had it my way I’d always be teamed up with a charity, maybe always with World Pediatric. I really liked working with them.

Running the Tour got a lot more publicity than your US run. You broke your first fundraising goal (of $100,000), and then your second (of $150,000). Has the attention changed the way you view what you did?

It didn’t change the way I viewed it — it had the same meaning. If anything it changed the things we did besides running. There were sponsor relationships to keep up with, and in general more to do besides the run, which was not a bad thing.

You decided to do the last 90 miles of the Tour de France in one day. Do you think that was a good idea? And would you do it again?

Right after I finished, I was telling Alex, “Don’t ever let me do that again.” But that was followed, a few days later, by an internet search for an ultramarathon. Even though I knew those last ninety miles would be really hard, I also knew I wanted to end that way.

I was afraid that arriving in Paris had been the emotional finish — I got there a day before the cyclists, and my brother and sister and sister-in-law were with me. But then I had to go to Corsica and do the Tour’s first few stages as my last few. I was worried that leaving Paris and doing the last 320 miles in Corsica — a barren, rugged island, I will add — would be psychologically difficult and tedious. I thought if I had this big scary goal at the end of it, I’d be motivated to get through the first seven days there. It gave me a challenge to look forward to.

Your blog account of the pain you felt on the last of those ninety miles was harrowing:

My head and face were burning up while the rest of my body was shaking with the chills. I had to stop and pee every five minutes but I had a thirst that I thought I would never catch up with. The physical pain on my hips and knees was bad, but what was the worst was the nausea that had been developing all day and which had bloomed into a full-tilt dizzying ocean of nausea. Talking was out of the question, and even just running with my mouth open was enough to make me want to puke. At some point I think I realized those bumps I had seen earlier must be sun poisoning, and the fever and debilitating nausea I’m experiencing must be because of that, but I also think I was so delirious with exhaustion that I just assumed that’s how it feels to get to 80 miles. And I’m sure it was a little of both.

Yeah. I thought, when I’d finished, that I’d done irreparable damage to my hips and my knees. But I’m running again now, and so far so good.

For both trips, you met a lot of people and got a lot of local support. What were similarities or differences in the relationships you made or established along the way?

At some point the US run stopped being about just running: it was about the people I stayed with, seeing these towns I ran through, and learning as much as possible. There was so much I got to see that I’d have never gotten to see if I’d just been traveling through the area.

In France, we didn’t have the ability, logistically, to stay with host families as often. But the nature and quality of the relationships was very similar. I’ve found that when you’re doing something like this, and you’re staying with a stranger, and you’re totally in the moment with them, they’re often moved to share their lives and their stories with you. In the space of twenty-four hours — or less than that, just dinner and breakfast — we formed friendships with people we’re still emailing with, we’re still Facebooking with.

What was it like having Alex with you in France?

Ninety-five percent of the time it was amazing. I don’t think I could have done this run alone. Logistically, the stroller wouldn’t have worked on the French roads. The thing that was distressing for me — and the five percent of the time when it was difficult — was that Alex was my support team but also the filmmaker. There were times when he was the only person in the world who could understand what I was going through, what this was doing to my mind and my body, but rather than being in a position where he could be compassionate, he had to be behind a camera. It was hard, but it had also been my choice, and I had to accept it. It made certain moments feel even more isolated.

Do you have a philosophy on running?

Running is a means of discovery on a couple different levels. You’re discovering yourself, what you’re made of physically and mentally. You’re discovering your town, or a foreign country, or the mountains — wherever it is you’re running. And you’re discovering not just what you’re made of but who you are, where you came from, what your world is and how you feel about it. I’ve relived so many memories and experiences in my mind while I run. It’s like meditating for an hour a day, which I don’t think many people do. To me, running’s like that — more of a moving meditation than a competitive endeavor.

I’ve got this memory of you one day at basketball practice in fourth grade, when you just started running laps around the gym. You were just like, “I’m going to run fifty laps around the gym.” Do you remember that?

I do remember that! I think it was because I was late to practice.

Yeah! It was self-assigned. No one asked you to run fifty laps.

It’s funny because in some ways I never considered myself a runner, but then I think back to running around the Lyseth gym, and I get it. And there was another instance at softball practice at Portland High where I was frustrated, and my coach told me to go run twenty yards down the road. Instead I ran all over Munjoy Hill and didn’t come back until after practice. I think the runner bug was in me earlier than I remember.

Earlier you said you like simply moving, getting around on your own strength. I think when we’re younger we have a more spontaneous joy-finder.

Right — instead of doing something and thinking, this will make me happy, we just did things, and we were.

Melinda Misener is from Maine.

All photos courtesy of Zoë Romano. More info about Zoë can be found at her website, and a day-by-day account of her Tour de France run is up at her blog.