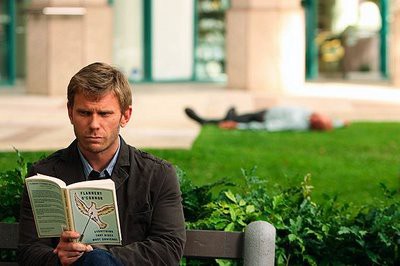

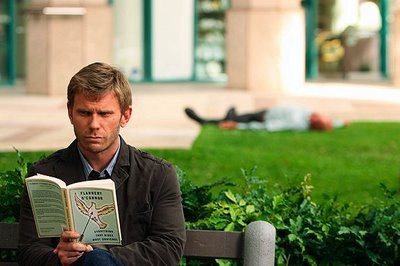

Flannery O’Connor’s Letters to God

For all of the deep fundamental religiosity in the work of American writers like Dickinson, Melville and Thoreau, Flannery O’Connor remains one of the only (and perhaps the only) national literary figure whose personal faith was lifelong and orthodox. The New Yorker recently published excerpts from the prayer notebook O’Connor kept as a 21-year-old studying at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and although the piece is subscriber-only online, it’s definitely worth seeking out a copy if this is a subject of interest to you. A bit from the beginning:

I do not know you God because I am in the way. Please help me to push myself aside.

I want very much to succeed in the world with what I want to do. I have prayed to You about this with my mind and my nerves on it and strung my nerves into a tension over it and said, “oh God, please,” and “I must,” and “please, please.” I have not asked You, I feel, in the right way… the frenzy is caused by an eagerness for what I want and not a spiritual trust. I do not wish to presume. I want to love.

[…] Please help me to get down under things and find where You are. I do not mean to deny the traditional prayers I have said all my life; but I have been saying them and not feeling them. My attention is always very fugitive. The way I have it every instant. I can feel a warmth of love heating me when I think & write this to You. Please do not let the explanations of the psychologists about this make it turn suddenly cold. My intellect is so limited, Lord, that I can only trust in You to preserve me as I should be.

“My intellect is so limited.” Oh, Flannery! Incidentally, you can read her knockout stories “Good Country People” and “A Good Man is Hard to Find” in full online, no subscriptions necessary.