Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Scary Stories by Women, About Women

by Jen Doll

I adore crime fiction, especially tales from the ’30s and ’40s and ’50s that fall into the noir genre, and I also love detective fiction, especially when those detectives are women. But there’s been a piece missing in my fandom for psychological thrillers, detective fiction, and noir. That’s the domestic suspense genre, which includes creepy tales of home, those who occupy home, and beyond: think “deceitful children, deranged husbands, vengeful friends, and the murderous wives they unleashed.” Sound good?

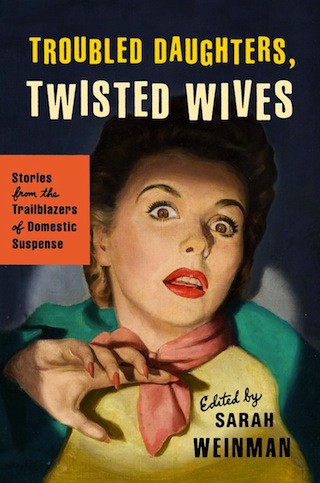

Sarah Weinman has edited “a salute to the real femmes fatales of the domestic suspense genre” in her new book Troubled Daughters,Twisted Wives, and it is just as chilling and excellent as one might hope. The 14 stories included in the compilation are all written by women — Patricia Highsmith, Shirley Jackson, Dorothy B. Hughes, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, and others; some names you might recognize, others deserve more attention — between the 1940s through the mid-‘70s, in a time in which women’s roles in the home and workplace were shifting rapidly. These aren’t just scary stories to read in the dark. They offer social and historical and feminist commentary, insights about where we’ve been, and where we’re going. I spoke to Sarah about her book, which is a must-buy for anyone who loves Gone Girl, but also, I think, for anyone who loves Raymond Chandler, too.

Sarah, how did the idea for the book come to you?

Originally, I’d written a piece for Tin House in an issue called “The Mysterious.” I wanted to explore why all these suspense writers, women, who I could tell had been critically acclaimed — they were winning Edgar Awards and selling well — weren’t cropping up in the discussions like their male counterparts.

In that essay, I wrote about “The Lodger,” by Marie Belloc Lowndes, about a husband and wife who are in deep financial straits. They take in a lodger, and he just wants to be left alone, he wants his food under the door. As this is happening there are Jack the Ripper-style murders going on. This was published in 1914, so I talked about that, and the work by Elisabeth Sanxay Holding, and then Celia Fremlin, The Hours Before Dawn, about this woman with two toddlers and a newborn baby. It was 1958, but she pretty clearly has postpartum depression, and her husband is a proverbial mansplainer. They take in a boarder and weird things start happening. After finishing the essay I had this lunch meeting on a completely unrelated matter. I can’t remember how I got on the subject, but it was so on my mind, and I was asked, “Why don’t you write a proposal?”

How did you put it together and decide what to include?

It took me a while to organize it. That first year was about finding the right author mix, the right stories, and finding out how to negotiate rights, which was a skill I wanted to learn more about. It’s a part of the publishing industry that’s vitally important. There’s no greater moment than being able to hear back from the widower of one of the writers, “It’s so wonderful that you’re going to honor my wife in this way.” There’s a real human connection that can be made. (I did an interview with Jack Callahan that’s on my companion website so people could know a little bit more about Barbara. She published 20 short stories, “Lavender Lady” [which is in Weinman’s book] was the second.)

What brought you to mystery, initially?

I remember reading Mary Higgins Clark’s Where Are the Children?, which scared me like crazy as a teen, and Loves Music, Loves to Dance. In college I really got into the mystery field, reading Dennis Lehane, George Pelecanos, S.J. Rozan. I guess my interest in the domestic suspense came in the last five years or so. I read In a Lonely Place by Dorothy B. Hughes. That’s one of my favorites; I find new things in it every time. She was amazing of conjuring up this post-WWII world and describing these strong women who were only seen through the demented perspective of her character. It’s very clear that they’re much more on the ball than he is. In her first book, there’s a spy element, but there’s also this woman in a marriage to this man, and maybe they’re breaking up and maybe they’re not. Her single women assert themselves, even though they’re rooted in their time.

What did you think of Gone Girl? How did the success of Flynn’s book impact yours?

I really marveled with the structure and loved what she did with Nick and Amy, how they were playing off each other. I think Gone Girl’s success is a boon in contextualizing this one. I feel there are more and more books published now that fit in the contemporary domestic suspense genre. They deal with psychological issues, societal issues. They’re relevant to woman, and everybody, and they’re so relevant to what’s going on now in this recessionary society. They seem to straddle boundaries more effectively than a lot of the police procedurals, the private detective genre, which I think is ready to come back — and I think if it does, women will be at the forefront.

How do you define “domestic suspense” in the book?

It ultimately ended up being a little broader than I thought it would be going in. I thought it would be by women, about women, and in most instances that was true. The stories are about mothers, daughters, elderly women, single women. It was important to bring in some authors people would have known. Patricia Highsmith, who really felt more comfortable in the skin of men, especially the male sociopath — her first short story is included as a “path not taken” tale. Then there was the Shirley Jackson story, which has a domestic quality that comes through. You’re running away from something, other people have an assumption, you try to break it, and you can’t. You’re chained by this inevitability.

What are some contemporary books you see as domestic suspense?

This year’s been good. Reconstructing Amelia, about a Park Slope mom who thinks her daughter has thrown herself off the roof of her school until she gets a text that says “she didn’t jump.” The Silent Wife, by the late A.S.A. Harrison, has been a word-of-mouth hit. It’s the most immediate comparison to Gone Girl, with the perspective of husband and wife, and so much going on underneath. Kelly Braffett’s Save Yourself is a literary thriller with a tragic but inevitable denouement. If You Were Here, which was done well before the event in Cleveland, and Hallie Ephron’s There Was an Old Woman. I feel that there are quite a lot.

In the stories in your book I see such feminist commentary, particularly in the reflection of the struggle to balance home life with aspirations and the possibility of careers. The dark side of home is that it can be a place in which you feel trapped…

It was interesting to see what was produced by these women who put aside their writing dreams for years, who juggled family, or who were lesbians, or who never had children. Helen Neilsen’s “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree” involves a character who’s been sleeping with a married man. She marries him and is harassed by phone calls, and has this suspicion that her husband will replace here with a younger model. The author worked in a munitions factory during the war and was a screenwriter in Hollywood. Whatever we know about her comes through in these novels and stories. Or Hughes, when people would ask if she was a feminist, she’d flat-out say no, but after writing 11 novels in seven years, she took an 11- year break, wrote The Expendable Man, and then never wrote novels again because she had to take care of her aging, ailing mother and her family. And with Barbara Callahan, her daughter told me, family always came first.

Why do you think these women and their stories haven’t continued to get the attention they deserve?

Ross MacDonald was married to Margaret Millar, and she was just as well-known and critically acclaimed as he was, and sold just as well, but now people don’t read her as much. It’s interesting that he got all the kudos but she didn’t have the literary recognition. We saw this with Elmore Leonard, who had his bona fides, writing into his mid-80s, but also with the way he influenced this larger culture. I wonder what will happen with Dorothy Salisbury Davis, who is 97. I don’t think she’ll get the same kudos in the same way. My larger point with the book is that I want more readers to read women writers. There are so many more that I haven’t been able to get to, and may not be able to get to. I’m saying, here’s the baton, I’m holding it for a while.

You talked about how these stories are relevant to us today. Can you expound on that?

Obviously I’m looking back with many decades of hindsight. But we’re still dealing with sexism and how to juggle motherhood with everything else. Career women didn’t just spring up in 1975. Women being marginalized when they are single and elderly, women having to struggle for independence and a career, those issues are part of today’ s culture.

What lessons do you think we can learn from these writers?

It’s interesting to see how women dealt with things when the options were far fewer. Some women still managed to have independent and fulfilling lives. Staking out a career as a writer could be seen as rebellion. It’s still very empowering and inspiring. It’s a good way to remember that this has been happening a long time, but it’s not over yet. You can’t snap your fingers and say, all publications will have equal numbers of male and female contributors or that these laws are just going to go away. There are resonances and that might seem depressing, but it’s also encouraging.

You wrote that your favorite stories from the collection might change regularly. What are they today?

“The Purple Shroud,” I’ve been feeling a great kinship with that one, and “Lavender Lady,” the Barbara Callahan story. I was glad to include a story by Davis. I visited with her over the summer, and being able to hand her the finished copy was beyond belief. She was telling me, “This is how I know this writer, this is how I know this writer.” She’s in pretty damn good shape for someone who’s 97.

What’s next for the genre, do you think?

It’s hard to predict. I know there are some books about to come out, like Just What Kind of Mother Are You?, thrillers with an added psychological and domestic bent. Two of the best practitioners out there are men — Harlan Coben, since the 2001 book Tell No One, and Lynwood Barclay, who merges the domestic with sardonic humor. Meghan Abbott’s Dare Me involves the subculture of teen cheerleaders, and Laura Lippman’s After I’m Gone has a domestic suspense-style situation that goes on over several generations. There are more along those lines, and as long as they keep selling well, I think they’ll continue. The genre will be redefined or tweaked according to the market.

What else do people need to know about Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives?

My goal is to give an overall context to this generation of female writers, and lend them some short-term permancy. This is a conversation I want to start. If some college professor would teach it as part of a course, that would be phenomenal.

Previously: “A Lady Who Followed Ever Her Natural Bents”: Happy Birthday, Dorothy Parker

Jen Doll is a regular contributor to The Hairpin.