Three Stories About Women and Tennis

The New York Times Magazine published its annual U.S. Open issue this past weekend, and it’s as excellent as ever (this is the same tradition that brought us both David Foster Wallace on Roger Federer and, a personal favorite, John Jeremiah Sullivan on the Williams sisters). This year we’ve got a long piece on Li Na, the Chinese player who is women’s tennis’s resident oddball now that Marion Bartoli retired (ish).

As Brook Larmer points out in his piece, the women’s game is at a sort of strange crossroads now: there’s no obvious hierarchy. Serena, when she’s healthy, could probably win every tournament she enters, but there’s nothing close to the four kings (Federer, Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic, and Andy Murray) of the men’s game. Li hasn’t known consistent success yet, and she’s one of the oldest players in the Top 30. She grew up playing in China’s system before opting out at age 22 to be with her boyfriend and study journalism, but she returned to the game in 2004 after successfully negotiating a better deal with Chinese authorities. (She’d previously been required to hand over 65 percent of her winnings to the government; she now pays about 8–12 percent in a given year.) Her relationship to the sport has been strained, even by tennis wunderkind standards:

Born in 1982, Li Na was, like many Chinese athletes, pushed into sports against her will. Her father — a former badminton player whose career had been cut short by the chaos of the Cultural Revolution — was the “sunshine of my childhood,” she said. Even so, he gave his daughter no choice when he enrolled her at age 5 in a local state-run sports school. Though she was a strong athlete, her shoulders were deemed too broad and her wrists not supple enough to excel at badminton. A coach persuaded her parents that she would have a better chance in a sport that few Chinese at that time had ever seen. “They all agreed that I should play tennis,” she said, “but nobody bothered to ask me.”

From the beginning, Li chafed at the harsh strictures of the state-run sports machine. China’s juguo tizhi — or “whole-nation sports system” — churns out champions by pushing young athletes to their limits every day for years on end. The first time Li defied her coach came at age 11, when, on the verge of collapse, she refused to continue training. Her punishment was to stand motionless in one spot during practices until she repented. Only after three days of standing did Li apologize.

Now, finally at peace with the sport she was forced into at age five, she’s trying to stay healthy enough to win a few more grand slams. Aren’t we all?

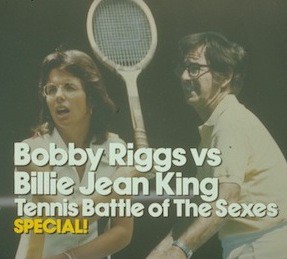

Read the thing in full, if you have time, along with the interview with Jimmy Connors, the former pro and coach who grew up on a “women’s game,” coached by his mother and grandmother. If you still have time for tennis (and WHO DOESN’T?), you can go read about how Bobby Riggs may have thrown his second Battle of the Sexes, the 1973 stunt match against Billie Jean King, to pay off a mafia debt.

Tennis, ye contain multitudes.