The Crossword Puzzle: Where’d The Women Go?

by Ben Tausig

“Congratulations to the four women and 34 men who debuted as constructors this year,” announced a popular New York Times crossword blog on the final day of 2012. If anything, the note was true to the genre: the crossword puzzle world received the numerical evidence of its gender disparity as just another bit of shrug-worthy trivia, even if no one seemed to know how those numbers came about. Although crossword constructors, editors, and superfans make up about as kind and tolerant (if, yes, also interpersonally awkward) a hobby enclave as you’ll find — and although we are a group whose passion is working through tricky problems — women have lately been excluded from creating and editing crosswords for unclear reasons.

In 2013, nearly every dead-tree crossword editor is a man: Will Shortz at the New York Times, Rich Norris at the Los Angeles Times, Mike Shenk at the Wall Street Journal, Stan Newman at Newsday, and Tim Parker at USA Today. I’ve worked with every one of them in some capacity, and spoken with all but Parker in person, and I’m confident that none are raging or even simmering misogynists. But editors can nevertheless be face-palmingly agnostic about byline representation. The typical discussion, which happens once a year or so on a blog, goes like this: Someone mentions that X crossword feature hasn’t published anything by a woman in three weeks, or that Y editor rejected 20 submissions in a row from a woman while running a slew of terrible puzzles by men. The editor responds by defending his gender neutrality, perhaps citing the much higher number of puzzles he gets on spec from male constructors. Q.E.D., the ratios are equitable, even if the total counts aren’t. “All that matters is the product anyway,” he might add.

It’s hard to measure the full extent of the gap, but from my 10 years of experience as a puzzle constructor and seven as an editor (of the Onion crossword, which is now the independent American Values Club), I can say that the landscape isn’t dissimilar from journalism and publishing as a whole. In other words, you don’t need to cherry-pick examples to demonstrate an imbalance. In June, the month before I wrote this, the Los Angeles Times had five female bylines and two collaborations between a man and a woman. That’s an effective total of six puzzles by women and 23 by men. The New York Times had five female constructors and one male-female collaboration in the same period, against 24 men. (“I don’t think the low figure reflects any gender bias on my part, since I don’t care who makes the puzzles,” Shortz told me recently. “When I look at submissions, the gender of the contributor doesn’t even register with me.”) One anonymous constructor told me that male puzzle editors often use female bylines to publish their own puzzles: “Almost all of the pen names are ‘female.’ Marie, [Lila] Cherry, Anna, Alice. I suspect this allows editors to give the appearance of a stronger female presence, without doing anything to solve the problem.”

Many professional and leisure communities have some manner of “woman problem,” and it’s true that video game development, construction, and Insane Clown Posse fandom make crosswords look egalitarian. The crossword puzzle is different, though: it has, in fact, regressed. The industry hasn’t been male-dominated since its earliest years; gender disparity has worsened in the past two decades. Many of the innovators who initially put crosswords on the map were women.

•••

The first crossword-solving celebrity was Ruth Franc Von Phul of New York City. Born in 1904, Von Phul’s life story could have been a promising outline for a John le Carré character. A well-educated Manhattanite, she later became a noted Joyce scholar and a Cold War-era cryptographer, but she first earned fame by being the fastest competitive crossword solver in America. Von Phul was in her early twenties just as the pastime was becoming a national craze with an epicenter in New York City, her home town. In the mid-1920s, nearly every newspaper was scrambling to promote its own puzzle feature. Bold-faced names were routinely photographed doing them, and musicians wrote hit songs with crossword-themed lyrics. Sitting New York Governor Al Smith and humorist Will Rogers each contributed their own crosswords to a book collection.

During the peak of the craze, newspapers like the New York Herald-Tribune posted Von Phul’s solving times as “bogey times” — the fastest that anyone had gotten through a particular puzzle, for sake of comparison. Von Phul won the Tribune’s National All Comers Cross Word Puzzle Tournament in 1924 at the age of 20, and again in 1926 at 22. She appeared on the cover of numerous national magazines; The New Yorker profiled her in just its seventh issue, in April 1925. (And a condescending profile it was: “you may consider what manner of hurt the cross word industry would have suffered had its official champion been a lady who didn’t photograph well.”)

As Von Phul was enjoying her star turn, the (arguably) most important person in the history of crosswords was developing her craft at the New York World. Margaret Petherbridge, also of Manhattan, worked as the assistant to Arthur Wynne, who invented the crossword in 1913. Petherbridge’s talent was clear as soon as she was hired in 1920. She quickly surpassed her mentor, and Simon & Schuster hired her in 1924 as an editor of the first-ever crossword book. And when the New York Times finally added a crossword in 1942, 17 years after the height of the fad (the Times was on it, even then), Petherbridge (now named Farrar) was an easy choice for inaugural editor. She kept her job until 1968, when she reached the paper’s mandatory retirement age. During her editorial tenure, Farrar defined the modern crossword, from rules to themes to humor. “Margaret laid down most of the rules and standards for modern American crosswords,” Shortz says today. “The puzzles she edited have a classical, elegant feel.”

The iconic square grid you recognize was not standardized until Farrar’s helm, and nor was the gee-whiz 180-degree rotational symmetry that makes the arrangement of black squares so lovely to behold. Older crosswords featured strange and sometimes chaotic shapes. Their clues, moreover, were absurdly dry (“One who visits” for VISITOR, and “I” for ME, for example). Farrar broke the seal on the kind of wordplay that made crosswords much more than a dictionary exercise. She made the game both elegant and funny, two things it hadn’t previously tried for, and her efforts made crosswords’ popularity endure.

Farrar is far from the only notable female crossword editor, despite being the only one the Times has ever had. Games Magazine, which had its heyday in the ’80s and early ’90s, was founded by Ronnie Shushan, and Jacqueline Damian once served as its editor. Janis Weiner edits today for Kappa Publications, and Jennifer Orehowsky for Games. Dell Champion Crossword Puzzles has historically been run by a majority of women. Coral Amende’s book The Crossword Obsession quotes Dell’s Erica Rothstein: “[Dell] was a very small office; only women. Kathleen Rafferty wouldn’t have hired a man to save her life. She was absolutely brilliant as an editor. She never, ever, ever got the credit in the puzzle world that she deserved. She made Dell.”

When I began creating crosswords in the early 2000s, the seeming equanimity was appealing. My mentor was New York Times regular Nancy Salomon, and I was a huge admirer of the eccentricity of Frances Hansen, who put her own poems in grids, and the inventiveness of Elizabeth Gorski, who specializes in visual grid effects, among others. I loved that the field wasn’t a boys’ club, which was how I was beginning to feel about music journalism’s (my other hobby at the time) Lord of the Flies quality. It wasn’t perfect, but it seemed like a refreshingly grown-up place to hang out.

Over the next decade, though, puzzles by women started to decline. Gorski ran her highest rate of puzzles in the late 1990s and early 2000s, transitioning to self-published work after that. Paula Gamache, another prolific constructor, slowed down significantly. Nancy Salomon, Cathy Allis, Sherry O. Blackard, Sarah Keller, Nancy Nicholson Joline, Stephanie Spadaccini, Karen M. Tracey, Dana Motley, and Nancy Kavanaugh — all New York Times staples once upon a time — have, to varying extents, faded from view. Frances Hansen died in 2004. The great Maura Jacobson recently retired from New York magazine, after 30 years. Although a number of young female constructors are doing exciting work today, their ranks have thinned.

•••

Sexism, like most –isms, can shift shapes cleverly, and most sexist patterns aren’t as loud as those stitched together by campaigning GOP pols. Crossword editors, as I’ve said, are rarely accused of harboring overt bias. To cite just two examples, Will Shortz and Peter Gordon have each made moderate but sincere public efforts to combat this problem, either by editing blindly or by making a point of including work by women in prominent competitions. But the byline bias remains. So where does it come from?

Some suggest that the problem does begin with editors, but on a level they don’t recognize. “I ascribe to a theory,” one up-and-coming constructor told me, “that we all tend to unconsciously ‘favor’ people who remind us of ourselves, and that this can lead to a whole host of self-perpetuating discriminations that we’re not aware of.” This constructor argues that crossword editors favor aesthetic tendencies, not types of people, but that the end result is the same. Certain themes or clues flatter male humor, and acceptance rates would tell us little here: if women perceive a stylistic editorial bias, they may never even reach the point of submitting their work.

The absence of prominent women in the field may do even more to discourage younger female puzzle makers. For Gorski, the second most-published constructor in the Will Shortz era at the Times, it was seeing Maura B. Jacobson’s puzzles in New York magazine that made her pursue the career. The first puzzle she ever completed, in fact, was a Jacobson puzzle.

“Everyone remembers their first crossword success,” she says now. “I solved my first Sunday-sized crossword, from start to finish, in a New York magazine puzzle, [and it] gave me the confidence to try again the following week. [Maura’s] puzzles were literate and funny. She is a superb entertainer. Seeing her byline each week reinforced a tiny spark of possibility: this woman had her own weekly gig in a slick, gorgeous magazine. Maybe I could make a crossword some day. I wanted to be like her.”

Others cite a deeper-rooted female crisis of confidence in intellectual endeavors. Deb Amlen is a constructor and the author of Wordplay, the New York Times crossword blog. I once visited her son’s elementary school to teach the kids about puzzles, and she noted: “Your last words to the class were to encourage everyone to think of their own ideas for puzzles. I watched the boys rush up to talk to you, while the girls held back or lost interest. Why do you think that was? Starting at [a young] age, girls get messages that other things that outweigh their intellectual contributions to society.”

There’s a history of crosswords as indicators of intellectual status: solving a New York Times crossword in ink is the clichéd high watermark of bourgeois mental aptitude. But no one has ever suggested that there is a lack of female crossword solvers, and some actually say that there are more of them. So the problem doesn’t seem to be one of participation by different genders, but of inequality in representation, authority, and economic rewards.

“As a solver, I can’t really speak to what has been happening in the editing and construction worlds,” says Anne Erdmann, a top-10 finisher most years at the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament. “But I can speak to the test-solving world. Most of the top male solvers are in great demand. Dan [Feyer] of course most of all, but Tyler [Hinman] and Howard [Barkin] as well. Most of them have multiple paid gigs to do this. Guess how many constructors have ever asked me to test-solve? One, and it is a female constructor.”

There is, as Erdmann suggests, money in this industry, which is small, but an industry nevertheless. Some of the work is of the odd-job sort: test-solving for books or syndicated puzzles, freelance construction, and so forth. But there is also latent economic potential in crosswords. The Times has somewhere north (perhaps by now far north) of 50,000 digital crossword subscribers who pay $20–40 per person each year, in addition to a legion of fans who buy the newspaper in whole or part because of the puzzle, not to mention a veritable empire of printed books that in total earn millions annually.

There can be rewards for entrepreneurialism too. As in so many areas of intellectual labor, the traditional models are being upended, and much is up for grabs: some people I spoke to for this piece suggested that technology is smoothing out the contours of the old playing field. A couple of app makers who jumped in early have done extremely well, and with more platforms for digital distribution, alternatives to the Times have sprung up all over. Paid digital subscriptions are becoming more normal, and Gorski, among others, has added to the ranks of these services with her weekly Crossword Nation puzzle.

Regressions, sometimes, can turn around. But who is positioned to benefit on this new playing field? And given that the current media environment forces people to take risks, it’s worth asking: Who is encouraged (or even allowed) to take entrepreneurial risks? And who will end up reaping their rewards?

The inherent problem with pinning hopes on new technology is that it might stall the hard work of mentoring and encouraging constructors who don’t look exactly like those who have already made it. Nepotism is the default state, and nepotism in crosswords favors men. I’m not sure this can be countered without greater recognition of the extent of the problem and a broad-based campaign of mentoring. In this regard, crosswords look quite a lot like other segments of the publishing world.

Insularity is an enemy to imagination. More and more varied participants in an art form mean fresh angles and ideas. Aside from inequity being troubling as a matter of power, it also impedes the experimentalism that helps art thrive. And Farrar was an experimentalist. The reason I (and many others) call her an elegant editor has at least as much to do with her crossword design concept as it does her editorial chops. Rotational symmetry, which she introduced from whole cloth, makes crosswords both more interesting to create and more beautiful as objects. This feature offers an organic coherence to the experience of solving: the bottom right is an echo of the top left, and so on. The sections of a puzzle can speak to each other in all kinds of ways, both explicit and implicit, thematic and non-thematic. Constructors have been exploiting this for seven decades now. The perfect square shape and maximum block count, too, are highly modernist structural achievements. In addition to being attentive to factuality and language, Farrar had an artist’s eye. Gorski, as a constructor, similarly sees and uses grids as palettes.

I wouldn’t suggest that emphasizing design in crosswords is inherently feminine, though I suspect there is a thread connecting Farrar and Gorski, somewhere along the line. Different minds give art a sustaining novelty. Puzzles require that kind of innovation.

Ben Tausig is editor of the American Values Club xword (avxwords.com), formerly in The Onion. He also writes the Ink Well alt-weekly crossword and has freelanced for the New York Times and many others. He has a PhD in ethnomusicology from NYU.

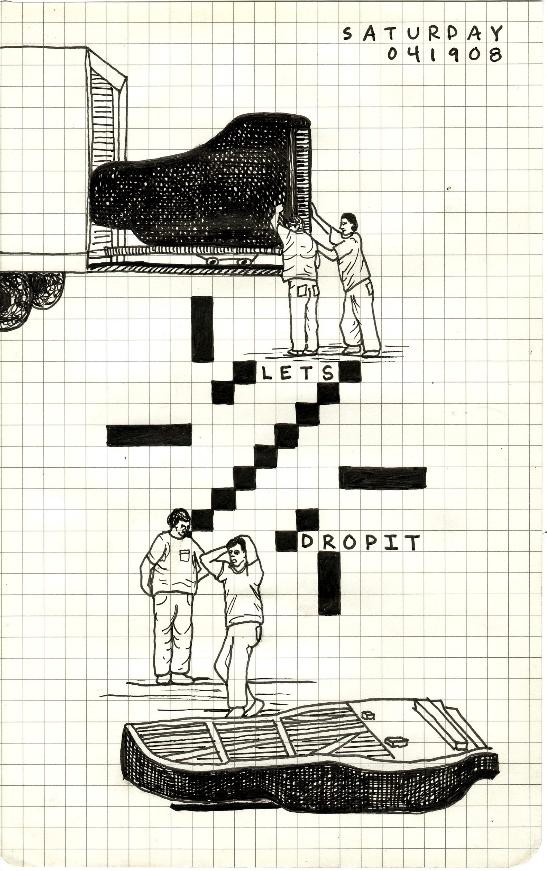

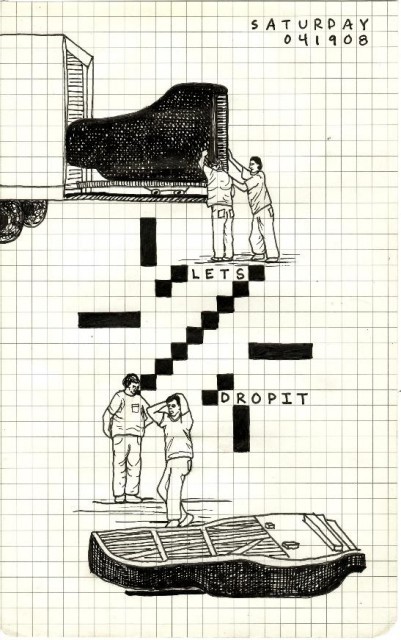

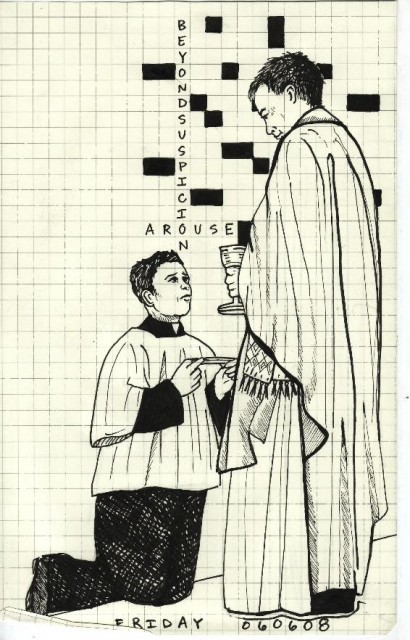

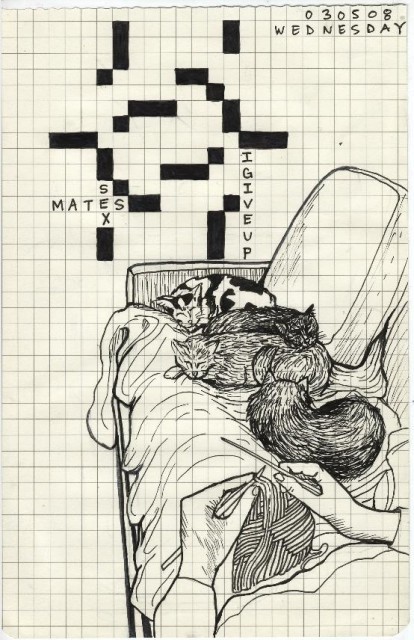

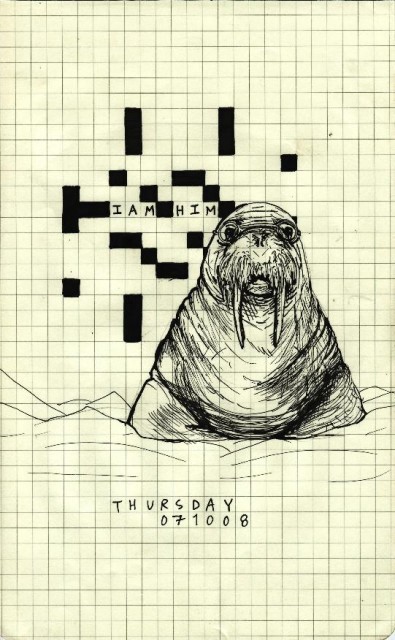

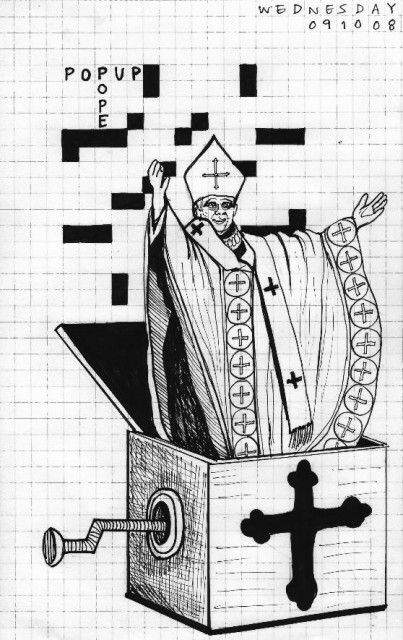

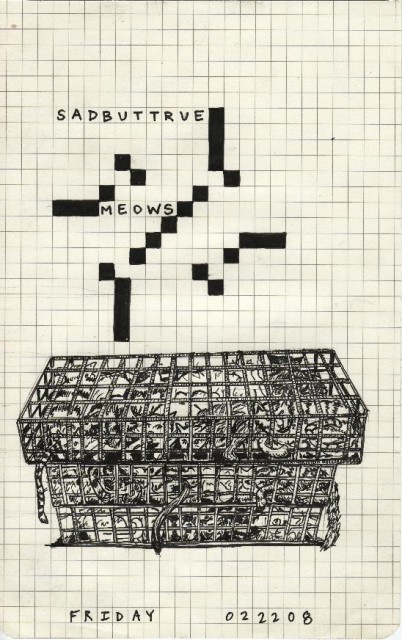

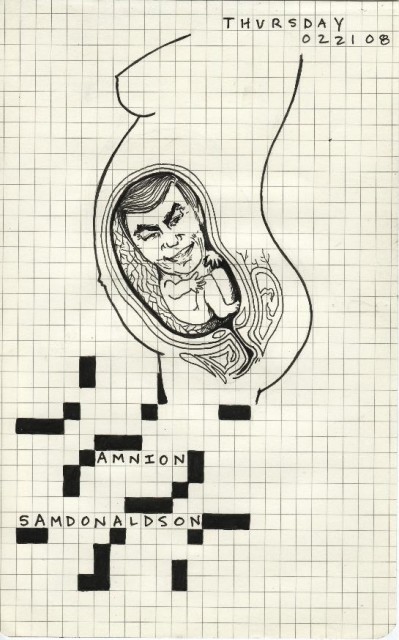

Crossword drawings courtesy of Emily Jo Cureton.