Interview with Cutie and The Boxer’s Noriko Shinohara

is a documentary about Ushio and Noriko Shinohara, two Brooklyn-based Japanese artists who have been married for more than 40 years. The director, Zachary Heinzerling, calls it a love story, and it is, at base: we’re given access to a tender working relationship that has plenty of darker subtext. “Underneath that playfulness,” Heinzerling has explained, “is the resentment that Noriko has for the way she was treated in the past.”

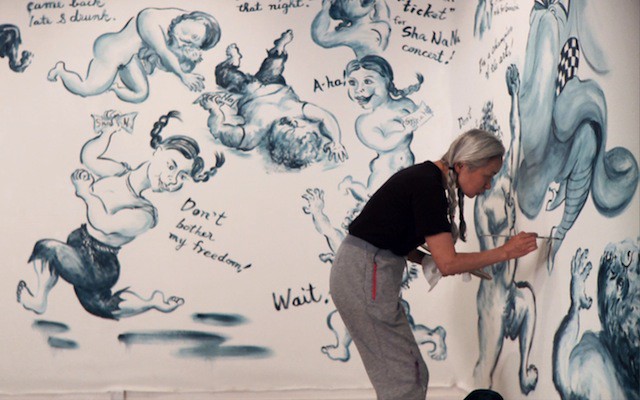

From the trailer alone, you’ll notice both Noriko’s sly humor and quiet control. She came to New York from Japan at age 19 to study art, and met Ushio, 21 years her senior and already an established artist famous for his “boxing” technique, just six months later. She was pregnant with their son Alex by age 21. Heinzerling’s film tells the story of their 40-year relationship through multiple mediums: we see old documentary footage of the young couple in which Ushio is mostly drunk and domineering; we see them in action today, as Noriko comes to terms with her newly sober partner and the two establish a more functional, loving relationship; and we see their history told through Noriko’s dark graphic novel, Cutie and Bullie, which could be interpreted as a memoir about the ups and downs (mostly the latter) of her marriage.

“I always had some doubt in me: am I really an artist?” Noriko told me in her Dumbo, Brooklyn studio a few weeks ago. “When I started Cutie I felt I am truly, from bone to skin, head to toe, an artist.”

Tell me about when you first came to New York. Were you planning to study art?

In Japan, there are not so many art schools. So to stay in the preparation school is common — one or two, a few years — between high school to college, or art university. So instead of waiting, I came here, to directly start and continue the art study. Half a year later, I met Ushio, which was the beginning of my destruction. And soon I became pregnant, which was double damage. It was like I had two kids. You know? Everything was very difficult. [Ushio] never grew. Even now I’m continuing educating and raising him. So to be a creative artist, it was a double shock. It has been so difficult.

But I continued. When my son was about two years old, I started painting again, little by little, and he goes to school, and by that time I paint more and more. I met [Ushio] when I was 19. And I had my son when I was 20. So my son’s 21 years younger than me, and [Ushio is] 21 years older than me. So I myself was young. It’s like I didn’t have my youth, my twenties, like that. I was raising my son.

How did Cutie and Bullie come about? Were you at a point where you felt far enough removed from the bad times with Ushio, where you could tell that story?

In June 2002 Ushio and I were brought to Inca, to Cusco, Peru, by a Japanese TV company. And we stayed more than two weeks for filming. In Inca, everybody we met had a braid. Young or old. So that year — and it was autumn — that year I usually had my hair in the back, but it felt too heavy. So I made braids like this and went to buy milk in my neighborhood. And a young man, like 25 years old, approached me, and then he said, “Hi Cutie.” It was 2002! I was 49 years old! At 49 years old most people have not much experience with a young man saying “Cutie.” So, huh! Since then I ask my family and my friends to call me Cutie, and they don’t do that! [laughs] But “Cutie” stayed in my head. And it was in 2003 or 2004, I have a friend who is gay and he is my best friend in 40 years. He lives in Texas so I always communicate with him. So one day I complained how bad Ushio is. And he said, “Punish him! Wear like a dominatrix and punish him with 16 inches of dildo.”

Of what?

Dildo.

OK.

So I made a small drawing of “Cutie” punishing “Bullie” with dildo. Until then I didn’t know the art of dominatrix and dildo. [laughs] Uh huh! I made a small drawing like that, and I sent it to [my friend] in Texas, and in that moment she appeared: Cutie is in that picture. She appeared in 2003 and 2004. In 2006 I started making Cutie stories, at the beginning of the year. It was at first all six-frame comics. And after I started, in 2007, the name of Bullie came out. Until then, Bullie didn’t have the name. Only Cutie had the name. And it became gradually the Cutie and Bullie story.

Is it therapeutic, to draw that out?

Not to say therapeutic, but I was confident I’d met my art creation.

This was it.

Yea.

You talk about finding your “queendom.” Can you tell me about that?

It was 2010. That time we had only one studio, so Ushio was dominating most of the place, and I was working near the window. And I had my etching press there, etching press here, and so my place was so small. And over there was so mixed with Ushio’s works and garbage. So one day I clean up everything, over there [gestures to other half of room], and I declared: “It is my country.”

You said that out loud?

Yea! So, without buzzer, don’t come in. I tell people, ring the buzzer, so people can come in. And Ushio needs the buzzer to come in. So while I’m painting, working, don’t talk to me! That time I established my country and my friend in Texas called it “queendom.” My queendom.

In the movie you quote Virginia Woolf, and it’s the same idea, right? The room of your own.

Virginia Woolf said women need a room with key and small money. But I didn’t have neither. So I just, without a wall or a door, I created my country, my room. Still, I don’t have much money. [laughs]

Maybe that comes next.

I hope.

What would you tell female artists who are seeking their own “queendom”?

To see the eye. To see the eye, and establish the eye, to see all work from outside. I learned it when I was doing etching. It was a new experience, because etching has a big process, in print-making. So with each process, when I see it, I saw the third person’s eye. That helped me grow up a lot, and to think about myself to look at my works, to be my own critic. Then I think: next step. The third eye is important, I think.

Can you tell me about your married life? In the movie you talk about being attracted to an opposite, and how love is something to endure. That seems to be a theme of the series, as well.

Without love, hate doesn’t come up. You know? If he’s just a friend, we could be just a friend. But the hate comes in because of the marriage. It’s too close. We inhabit two spaces. It’s kind of idealistic. It’s a luxury. And even the separation is luxury for me, because I couldn’t separate him, because I don’t have any talent to earn money, and I didn’t have much chance. And if I wanted to be the independent, I knew I had to give up my art, because raising a child and earning money is so difficult a task for every woman, except those with a special talent or a special source. And here especially, far away from my family, it’s so difficult. So I needed to stay here. Even if we had a big problem or a big fight, we have to go together, work together, live together — otherwise our life would be ruined. So, just not to ruin our life, we had to stay together.

In the movie you tell a reporter that marriage is like “heaven or hell”; that you and Ushio “are like two flowers in one pot. It’s difficult. Sometimes we don’t get enough nutrients for both of us. But when everything goes well, we become two beautiful flowers.” I’m guessing it was more hellish when you were living with Ushio’s alcoholism. [N.B.: Ushio developed an allergy to alcohol late in life.] How does it feel right now, with the movie coming out?

Now, [Ushio] cannot drink. Before that, because of alcoholism, it was so difficult to talk to him. He could understand only the things he wanted to. Before 2006 was my worst time. But all of the sudden, he cannot drink, so gradually he gained his sense and he’s even better. It’s one of the best times in our 40 years of marriage. Because of the film, I think he saw that. He saw me through the camera eye. So now in front of the people he’s trying to look at me differently.

Do you think Cutie could exist without Bullie?

Throughout my life, Cutie wasn’t born. So in a story, without Bullie, Cutie doesn’t exist.

There’s a running joke in the movie about you being Ushio’s assistant. But you do take that seriously. You’re his harshest critic.

He’s technically smart and a very technical person. So he’s good at involving other people to his work. Whether it’s me or other people helping him, it feels like we are part of his works. So it felt great. With that thing, he’s so good. But after that, gradually I felt, no. It’s not my work. Gradually, I felt it. So I stepped out, and stepped out, and tried to think only by myself. I tried to establish my space, and more space — even in the dishes, OK? Even in a cup I establish myself.

And that got bigger and bigger.

Yea. So gradually he understood I was beyond his territory. That time I knew he became a little lonely. But other people came, and with them he is the same. So I knew he doesn’t need me. He didn’t need me. He needed somebody, just somebody. So it helped me to establish myself. If he was a lovely person, I couldn’t do it! [laughs] His egoistic way helped me establish myself.

In the comic you see Cutie’s face get red as her anger and resentment builds toward Bullie. Was that an outlet for you, for your anger?

Anger is deep. But I use the comic as expression. I would say she was sad. Sadness is even more deep than anger.

In the movie you say in very clear terms that you don’t believe in happy endings.

I don’t believe in the happy ending. You know, everybody wants to, say, at the end of their life, to maybe die satisfied, die quietly, or die comfortably — surrounded by many friends or family. But my hero is Caravaggio, and he died young, struggling, but continuing with his art. So I want to die with my brush in my hand, and to die with art. Making art is always struggling.

Can you imagine making art without struggling?

My art process is kind of struggling, and thinking about changing myself. If I had the money, my studio could be more cleaner, or maybe I can hire an assistant, but still, creation is not so simple. Happy ending is a kind of lie. Creation has to be the truest to the artist’s heart.

You said you feel like the series is truly your own work. Do you think that’s an age thing, coming into yourself as an artist?

In high school, in Japan, everybody studied Greek sculpture and drew the Greek sculpture. And you’d go through the Renaissance paintings and the Modern art, and always there were masters, all over. Museums are full of masters’ work. And I felt too close to them. It’s like copying them. So even at first when I made a big, great painting, I couldn’t feel an artist. But when I created Cutie, I felt, it’s my own work. Nothing is copied from somebody. Until then I tried to be like “that,” or to be like “them.” But not now.

Art itself is a very difficult job, and I have many old paintings or etchings and many other things — not all Cuties — and before that, you know, even when I did good, I always had some doubt in me: am I really an artist? And even after I made a big, good painting, I still had doubt in what I am, because I just felt I was chasing the old masters. Caravaggio is my god, and Caravaggio is great, but not me. Before I started Cutie I always asked myself if I’m an artist, but at that moment, I felt I am truly, from bone to skin, head to toe, an artist. And I’ll die an artist.

Interview has been condensed and edited.

Press images courtesy of RADiUS-TWC. Cutie and The Boxer is now playing in New York and Los Angeles. See the trailer here and find screenings near you here.