Teaching Trayvon

by Teachers

The Hairpin reached out to a handful of teachers across the country with a tough question (though no more difficult than any other question America’s teachers face in a given work day): How would you teach the Trayvon Martin case, and George Zimmerman’s acquittal? What is there to say, and what is there to be learned? Their very thoughtful answers follow.

An English teacher in Alabama:

In a place like Alabama, this case is tricky to even discuss in the classroom. I would be willing to talk to my students about it if they want to, but I would be hesitant to “teach” it — especially because I teach literature. However, I often use real news stories or events from history to connect with the literature that they study in my classroom. I encourage my students to make connections to self, other texts, and the world while reading.

This story could connect with Richard Wright’s Black Boy in the way Trayvon was viewed as an “other.” Richard is often singled out in that book and assumed to be doing something bad. In reality, he does do some bad things, but he’s mostly just a kid. Kids do bad things and learn from them.

I also think it would be a good topic for a free write. We do these in my class after the bell rings. I could ask the kids something like this: “Think of a time when you felt like you or another person fell victim to a great injustice. Explain the situation. Why did it happen? How did it make you feel? Did it change your view of the world? If so, how did it change? What would have taken place in your perfect world to make the situation right?” After they write, I ask them to share with someone. Then I open the floor to those who would like to share with the whole class.

Another way to approach it could talk about vigilantes. Think about the scene in To Kill a Mockingbird when the mob comes to the courthouse for Tom. Also many of Faulkner’s short stories discuss mobs out for justice.

I could ask students: Have you ever felt so “in the right” that you took matters into your own hands? If you haven’t, what kind of situation might motivate you to act rather than ask for help? Explain the situation. What kinds of consequences might you/ did you face if/ when you do/ did it? What if you were wrong about the situation?

The thing is, I see Trayvon Martins everyday. They are in my classrooms and in my neighborhood. I worry about young black men and their prospects in a world where a man is able to kill one without being convicted of something. Even if it isn’t as simple as that, kids will see it that way. Rednecks are holding their heads a little higher and tapping the guns on their holsters eager for a stand your ground moment. That is what scares me most. I try to teach for social justice in a state where the poor are carrying the biggest tax burdens and often the victims of injustice. Poverty motivates some people to try harder, a small group to resort to criminal activity, a large portion just try to make it and live under the radar, and it leads some to give up. I try to encourage kids to do the most with their gifts and live life with integrity. Stories like this makes work more difficult because it makes kids lose hope.

Cathy Grasso, a high school teacher in the South Bay area of Los Angeles:

When the Trayvon case began my students were asking about it, and about what I thought. In general I try to let students talk about this kind of stuff without interfering with my views. Which is mostly what I did, at that time.

At this point I think I would bring it up as a current event. I would ask them what they know about the case. I would ask them if they understand why Zimmerman was found not guilty (lack of evidence that it wasn’t self defense). I would spend a good deal of time explaining that. Then I would ask, if they disagree with the verdict, what are their ideas to change the way cases like this are handled.

I would also use guiding questions, like why did Zimmerman follow Trayvon in the first place — how are first impressions important? Do you judge people by what you see? How has that maybe been damaging or harmful to others in the past? And perhaps I would make a few Juries and give them the evidence and see what they conclude.

I would also want to do a brief bit on how the messages and images on Trayvon’s phone influenced America. I think it would be interesting for them to talk about how his reputation was tarnished by stuff he had on his phone.

A high school college counselor in California:

Stories like this makes work more difficult because it makes kids lose hope.

I think the Trayvon Martin case is a really important thing to talk to students about. Keep in mind I’m not a teacher — I’m a college counselor, so I wouldn’t actually be leading discussions or planning a curriculum on something like this. But for my school particularly, which is very open about issues related to race, I have heard some of our black students talking about how they really look at the world differently when they’re out and about (and particularly as it relates to law enforcement) and trying to impress upon our white students why this is.

I think it’s so important to open up a dialogue about why this has touched a nerve with so many people. I think it’s because it just seems so unjust and incomprehensible to most that an unarmed teenager could be killed and his attacker get away with it — and I think it’d be interesting for students to look at the laws in Florida and see WHY the jury made this decision. It may be unjust, but WHY was it made? And maybe it’s the law that’s the problem in this case? And what can we do to change that?

Lindsey Hunter Lopez, a high school English teacher:

If I had been teaching an 11th grade English class (my usual gig) during George Zimmerman’s trial, students would no doubt want to discuss the verdict and share their feelings about Trayvon Martin’s death. However, as a teacher, I’m careful not to let my personal opinion be known when it comes to… well, anything touchy. Teachers know all too well that discussing touchy subjects can lead to disciplinary action, or even job loss. (Last year a teacher was fired for assisting with a student-led fundraiser for Trayvon Martin’s family.) Race, gun control, youth culture — there are many touchy issues involved when it comes to the death of this young man. Though it could be risky to bring this current event into the classroom, English teachers run into hard topics naturally; we teach literature, after all. How would one teach The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, for instance, without addressing “the N-word,” and its historical (and current) context? Not very well.

So I’d welcome discussing Trayvon, and I’d do my best to facilitate in a neutral way. I might begin with a relevant journal prompt, linking the class reading to the tragic event. Then I’d open things up to the students, and ask if anyone would like to summarize the violent event and the subsequent trial. I’d clarify as necessary, and call for comments or questions. “Why does Trayvon Martin’s death seem to touch a nerve with the American public?” I might ask. “Now that the trial is over, why are people rioting?” Hopefully this student-centered approach would lead to the all-important “critical thinking” (a term often bandied about in education), as well as empowerment through expression.

Alex Robins, a middle school social studies teacher in San Francisco:

Every day, my students and I try to make some sense of why past events occurred, how they affected their surroundings (people, the environment, geographical conflicts, etc.), and how these effects influenced life going forward. This case and its verdict show different sides of the United States criminal justice system in action and prove how complicated a criminal trial can be with regard to public opinion, state and federal laws, and questions of race and class in American society.

The most important thing my students can learn from this process is to get their facts straight. In the age of the internet and opinion blogs, hearsay and innuendos tend to carry the day. The facts of the case and the laws of the land should rule. When students make an argument in a discussion or as part of a research paper, they have to back this argument up with concrete, clearly cited facts. This process is valuable for life in high school, college, and into adulthood. For this trial, the jurors were presented two separate stories with few definitive facts. Ultimately, they used the information provided by the trial and their own thoughts and opinions to solidify their verdict. This brings up the second thing for students to learn from this trial: being a juror or judge is incredibly difficult. No matter the outcome, someone is usually outraged.

It would be great to think that incidents like the Trayvon Martin/George Zimmerman case are rare. However, similar crimes and trials occur constantly in this country with much less fanfare (in 2012, another 17-year-old Floridian was shot to death in his car for apparently playing hip hop music too loud; the defendant has pleaded not guilty and has used self-defense as his alibi). My students all have opinions and thoughts about this case and the issues it involves. I believe these opinions are valid and I want to honor them as best I can in the context of a classroom discussion. These students have had different experiences growing up in San Francisco as African-American, Latino, and Asian kids than I had in my sheltered, suburban life. I want to share my thoughts and show them the viability of their ideas and experiences.

As a class, we can focus on the facts of the case and why the debate itself is important. If we contextualize the incident, empathize with each actor, and fit these ideas into the bigger picture of criminal and social justice, we can hopefully improve on both the quality of our argument-making and the understanding of the problems that still exist within our society. Maybe then we can begin to make a difference in our communities and in our country.

Maureen Costello, director of Teaching Tolerance at the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Ala.:

Teachers need to make room to discuss this case and allow students to ask questions. A 2nd grader might wonder why there was no punishment for a person who killed someone. An older student might express outrage at the verdict, or denial that race was an issue. How teachers talk about it will depend on the age and, sadly, race of their students. Students who have never experienced profiling or the presumption of guilt need to know that their expectation that the system works isn’t shared by everyone. And students of color, whose parents have had “the talk” since they were little, and who live with the experience of being distrusted, need to know that someone understands. What’s utterly important is to be willing to talk about injustice and the work that lies ahead, and to engage students in productive thinking about how their generation can effect change.

Abe Cohen, a teacher at a transfer high school in the Bronx:

To preface, I’ve had a tough time writing this — the decision (and implications of that decision) came as a blow to me. The rest of this email is me trying to figure out an answer to the question. I seriously don’t have a good answer, and addressing Trayvon is going to take a lot more thought and work than what’s been done below. Like many, I am still trying to wrap my head the difficulties, and apparent complexities of the issues at hand. Decoding racial dynamics in this country just got a lot more complicated (or so I thought). My students’ reactions, however, were much simpler: “No shit.” They’ve been dealing with stop & frisk for years, and mayors/ police chiefs who have claimed that nonwhites aren’t stopped enough.

As you may imagine, this is a particularly difficult issue to teach, and reifies the disturbing power dynamics of a mostly white teaching force working with mostly nonwhite students. Parents, for the most part, do not confront the same historical (and present) baggage that many teachers (including myself) must address when facilitating a conversation around race history in the US. Despite the levels of discomfort the topic brings up, there needs to be some interrogation of the topic. Ultimately, this is such an important and indicative decision that it needs to be addressed. It’s probably important to note that, like many subjects, having students facilitate this discussion is far more powerful (and much less problematic) than teachers “teaching” the case. This is one of a handful of high-profile, nation-wide criminal cases that has existed in the Internet age. The prevalence of available primary source information, and the overwhelming amount of commentary that is immediately available, gives students unprecedented access to understanding and evaluating the decision. (Check the Wikipedia page for the case: at least the entire 911 call is there, among other sources). This case presents an excellent opportunity to control their own learning, and make evaluative judgements in a larger societal context.

Defining the extent to which I will discuss this with my students will probably be student-defined. Some will, rightfully, not want to talk about it; being confronted with the fact that Florida law allows people to hunt and kill black youth isn’t particularly comforting. Requiring students to remind themselves of a particularly disturbing and very real element of race relations in the United States may not be an (white) educators’ place. For me, after all, the distinction is philosophical; I probably will never have to deal with being confronted about being in a place I shouldn’t, while my kids have already found plenty of ways to deal with it. The kind of maturity, rationality, and patience that youth need in such a situation is frightening.

For me, after all, the distinction is philosophical; I probably will never have to deal with being confronted about being in a place I shouldn’t, while my kids have already found plenty of ways to deal with it.

Most commentary on the case has ignored or marginalized youth voice. Discussions around the subject have largely focused on the difficulties of being black in America, and have rarely confronted the associated difficulties of being young and black. In terms of school, and in much media, this case is particularly interesting in the canon of court law and US history: how will this case play into federal and state rights? What about McKlesky v. Kemp? How does it relate to the Civil Rights movement? Obama’s election? The set of questions my students must ask and answer (for penalty of death) is different: how do I walk around outside? Should I go to other neighborhoods? How do I deal with strangers? Should I try to look less “suspicious”? If so, how? And what does that even mean?

Within the context of our current school system, it’s important to note that teachers will probably need to make curricular sacrifices to address this; Trayvon won’t be on any of the Regents tests, and will not be part of city, state or national curricula for years to come (if it is at all). Like many other educators, I face the problem of choosing what to cut to make room in the school year, in addition to molding discussions about Trayvon to meet standards.

Dr. Imani Perry, a Princeton professor and mother of two:

Have you ever seen a small plant that has a splint holding it up? Growers do that when the plant is precious, but the ground on which it sits isn’t quite right for that little green shoot to flourish. I think of raising children in the United States in similar fashion, especially when it comes to matters of race. The earth is parched, the winds are whipping. A boy not fully bloomed was chopped down dead and his killer walks on, weapon in hand. My two sons, bright, creative and kind African American boys, aged 7 and 9, both wept when they heard that George Zimmerman had been acquitted. They were afraid he, or others like him, might come for them next. I did not anticipate that their young lives would be as much defined by the tragedies of the murder and execution of Trayvon Martin and Troy Davis, as by the historic era of the first African American president. They already know the brutal truth of racial inequality, and that they are called to wage the battle against it, just as their forefathers and mothers.

It never occurred to me, their father, nor our extended family members to avoid talking to the boys about racism and bigotry. We were raised on race talk, and it is their inheritance too. I believe that if children are guided honestly through the reality of the world in which they live, it will help them build resilience.

And yet, they also need protection, they need our tender nurturing and splints to hold them up in the process of developing the fortitude to meet a cruel society. This care requires that we speak directly to them when tragedies occur, yet not allow them to be inundated with televisual media and round the clock chatter about the subject. We ought to use age appropriate language, placed in the context of our values, about how the world ought to be, and what we can do to contribute to that vision. We must expose them to the ways we build character and community, rather than allowing them to be overwhelmed by terror and sadness. They must know their inherent value and hear about it more than they hear about how they may be devalued.

My sons attended a rally with me after the Zimmerman verdict and I told them “See all these people here? We are part of a community that extends across this country and world, that fighting against injustice.” In that moment, I wanted to help them transform their individual fear and grief into a sense of collective purpose. And I think this practice is relevant for all children, not simply those from groups whom are subject to bigotry. Because while on the one hand I am training my sons to develop resilience in the face of the racial injustice they will encounter, I am also training them to approach the world with full recognition and appreciation of the wide spectrum of human beings, some of whom are quite different from them. They know they have an ethical responsibility to humanity, animal life, and nature; to care beyond their immediate experiences. We talk about gender and sexual orientation and disability and mental health along with race, ethnicity, and language. They are encouraged to be critical and analytical, to use those enormous imaginations to journey into the interior lives of others. Together we create gardens of possibility in the parched earth. If we grow the babies up right, they just might redeem us all.

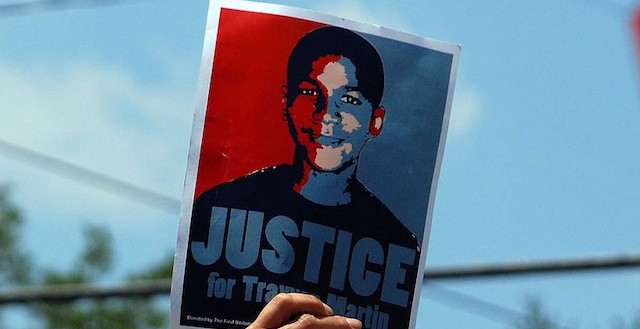

Photo via werthmedia/flickr.