Manly Me

by Rebecca Scherm

When I was twenty I sought out a full-time internship at my favorite men’s magazine.

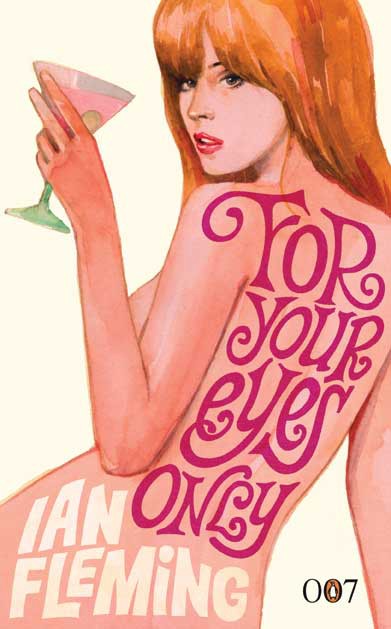

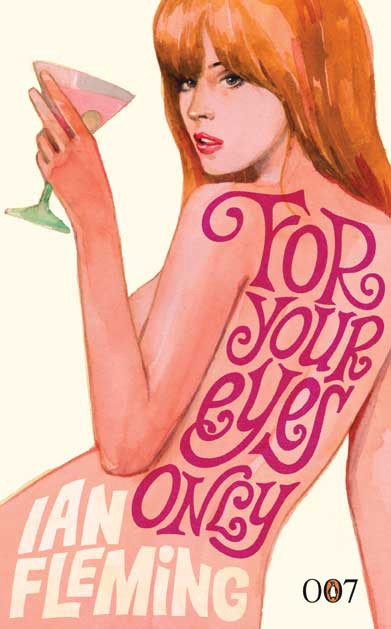

I killed the interview. I wore my first pencil skirt and sat at a conference table across from four men. I professed my love for their magazine’s ambitious features as well as its wit and bombast, and when they asked about me, I told them about a paper I’d just written on changing Cold War representations of masculinity as seen in the James Bond movies. They asked about my favorites, and I said I preferred the dirty pulp of Ian Fleming’s novels to the movies, which I found watered-down and neutered. I may have actually said “neutered.” I had them laughing: later, the young editor who became my supervisor told me it was the best interview he’d ever seen. My thirty-minute performance as my then-ideal, the girl who acts like a guy but doesn’t look like one, my Walter Matthau-in-a-miniskirt routine, had sold them.

This wasn’t a performance I could sustain. No doubt that editor was confused when I began my work there absent all chutzpah, nervous and anxious to please. I had presented, initially, as someone who pleased by not trying to: the cool girl. My fellow interns were men a year older than I was, out of college. I liked them and envied their laid-back-yet-irascible attitudes, the ideal for male magazine writers. Maybe they were naturally that way, or maybe I was so intimidated by my own inexperience that I only thought so.

Like a lot of women, I didn’t take any women’s studies courses in college because I didn’t believe then that sexism was an issue in my life. I didn’t call myself a feminist either, probably because I thought it would make me less desirable. I had a long-time boyfriend, so this “desirability” was about my self-worth, not practical application. And yet, I was obsessed with the male gaze: I liked the intellectual mirror-trick of looking at men looking at women. At the time, my interests were a bouquet of kitsch-masculinity: James Bond, 60s Playboy, Andrew WK, and horror movies where women were always screaming in nightgowns. I loved this men’s magazine and I loved the fact that I loved it.

That year, I’d been reading about secretly-female pin-up artists who had learned to mimic male fantasy and subtly, subversively tweak it. I was an artist then, and I thought working at this magazine (oh, it’s such a boys’ club, everyone said, which thrilled me) was a little like that — going undercover.

But I was never as ironic as I tried to be. Really, I just wanted to be the girl who got into the boys’ club.

***

The first week, we were given a tour of the magazine. In the art room, a cover shot of a movie star my age was being airbrushed to lad-mag standards. “She has sooo much cellulite,” the designer said, bemoaning the extra trouble she’d caused them. I told that story to my friends later, excited at this little insider nugget (it really is just like the internet says!), but instead of, you know, freeing me from hopeless standards and all that, I bought discount Spanx and started wearing lipstick. Not even a week in, and I’d drunk the Kool-Aid.

It didn’t help that my desk was outside the office of a loud and unpleasant man. Every day he brayed into his phone about his dinner reservations and, in what was essentially an endless game of F-M-K, who should be in the magazine. In the 650-ish hours I spent there, I heard his brisk evaluations of countless famously beautiful women, who was hot (so hot he dropped to sotto voce) and who looked like a dog or a horse or a man. This guy impressed no one — eye-rolling abounded — and yet, in a chiefly heterosexual male environment where women’s relative beauty was discussed constantly, it was impossible for me not to position myself on the spectrum that seemed to hover over every woman who appeared in the office.

There were very few women on the floor, and only two in their twenties. To me, they represented a choice of types: one woman was a tomboy who was always casual and unruffled, sexy but never made up. She had a husky voice and a kind of relaxed swagger. Her name was Jen or something like that. The other woman (I’ll call her Stacy), very nice and friendly to me, wore high heels, eye shadow, and, once, a tight but fluffy white sweater dress. She always looked worried. Jen was in the boys’ club; Stacy was not. I definitely wanted to be a Jen.

The types themselves aren’t important. The thing that’s so discouraging to me now is that I was doing this typing, both to other women and to myself, and that the right answer was the one the boys liked more.

I became simultaneously worried about being pretty enough and being manly enough, a word that’s only sort of a joke, since the magazine was so fixated on it. My boyfriend and I had one of those fungal arguments (it started small, but oh, how it bloomed) about whether I was trying too hard to be one of the guys around his friends. That accusation has three stingers: that telling dirty jokes or playing beer pong equals “being a guy,” that “trying too hard” is actually the gravest error, and that whether I was trying or not, I was definitely, definitely locked out.

The interns did the research for the short regular columns, and we could do it however we liked. I interviewed Annie Sprinkle, Ron Jeremy (people only wanted to talk about his penis, he complained, and so I asked him about his pets), veterinarians, professional rafters, forest rangers, and Pauly Shore, who would only speak through his assistant, who had turned on speakerphone, so everything Pauly said started with “tell her this” and “wait, not that,” and was then repeated by the assistant to preserve the illusion of Pauly’s …something. In most of these conversations, all parties hoped or pretended to be more important to our work than we really were (Annie excepted). I loved to interview people on the phone: I felt smart and useful, and for a few minutes, the FMK spectrum over my head disappeared.

In October, a mid-level editor asked Stacy to compile the “For Her” holiday gift guide. The parameters: an assortment of luxury goods and one set of lingerie. Stacy asked me for help when he rejected all her lingerie choices. After a few more rounds, he explained what he wanted: a hot photo that looked like something they would have shot, since there was no time or budget to shoot anything. The lingerie was just so they had a reason to run such a photo big on the “For Her” gift page. We had been suggesting things we liked — I remember a cashmere bra — but in the end the editor found something himself where the model “worked” for him. Stacy and I had failed, but not at choosing lingerie.

“Would you wear this?” the editor asked when he had found the photo.

Sometimes, your radar is working even if you can’t tell exactly what it’s telling you. In that environment, the line between gross and professional could blur quickly, or else too slowly for you to realize, like a frog in hot water. In wanting to be the girl intern at this men’s magazine, I’d jumped in the pot. Of course I’d expected it to be a sexist environment, I just thought that wouldn’t bother me. You know: “She’s cool.”

The week after, that editor had a contact lens fall out at lunch, and I was chosen to fetch his replacements. That worried me. When I handed him his sack of contacts, he thanked me by noticing me — in theory, all any intern wants.

“What have you done here? Sex, the lingerie beat, and… contacts?”

Sex-n-Errands? “Yep,” I said, too embarrassed to correct him.

He gave me this awful look, a sort of skeptical leer. It was such a small moment, but it was the moment. No, I didn’t like how he’d looked at me, but I was more upset about my own timidity, which I saw as my failure to be a Jen. I’d totally Stacied out. I was definitely not in the boys’ club. It wasn’t until much later, when I wasn’t working there anymore, that I finally got that Jen was not “a Jen” and Stacy was not “a Stacy,” and that maybe that editor’s sexist typing of me wasn’t any worse than my own. And that’s the moment I remember as the beginning my own feminism, though it took a while to jell.

This isn’t to lump together all the men at that magazine — many were great — or to suggest that I was trampled in some hog-call of cigar-smoking pigs in velvet jackets. What I learned working at a men’s magazine in college is that I had so deeply internalized sexism that I didn’t see it even when it was looking right at me from all directions: that sometimes, those eyes were the only eyes that I’d see.

To want to break into the boys’ club because it is a boys’ club, you have to believe that it’s worth breaking into. Like the fantasy of taming a wild animal or having the meanest dog on the block or dating men who don’t like women very much, the promise of earned entrance to a boys’ club is that you will feel chosen, exceptional: you are not like the others. You have transcended your gender. And you have done this not because you think your gender shouldn’t matter as much as it does, but because you think the boys’ club must be better than any of the clubs that will have you. You know, like Groucho said.

That one took a long time to unlearn.

***

The art project I’d planned (brace yourself) had been to secretly make copies from the magazine cover archives that I would then draw on panes of glass using etching fluid, which I would tint white and not wash off. I may have offered my teacher some lofty idea about ghosts and memory or some bullshit, but this was about me, as a young woman, drawing sexy women in a medium that would look like dripping jizz.

“Jesus,” my beloved artist mentor — a laid-back-yet-irascible man in his sixties — said. “You’re working where?” He started laughing and he could not stop.

When I was a little kid, my dad used to take me to Hooters for lunch on the weekends. Once, we arrived while a waitress was scrubbing the big windows outside. When they’d come in that morning, she said, there was a strange goo all over the windows. “Like raw chicken juice,” she said, scrunching her nose. I think that’s where I got the idea for the etchings.