D.I.-Why?: Emily Matchar on the Allure of the “New Domesticity”

by Amy Gentry

I first stumbled across Emily Matchar’s website in the aftermath of my December 2011 wedding. Planning the wedding had unleashed in me a seemingly endless energy for DIY projects, and for six months I crafted, thrifted, embossed and antiqued everything in sight. I had recently acquired a PhD in English, but found myself weighing the possibility of starting a crafting business rather than pursuing an academic job — a cheerless task in the middle of the worst academic hiring slump in recent memory. Compared with the prospect of slaving away in adjunct positions, dragging my husband from town to town for visiting professorships in Idaho or Nebraska, and risking delayed or denied tenure when I decided to procreate, the idea of painting vases to look like antique mercury glass for a living was… appealing. And I was good at it! Everyone loved those repurposed vintage postcards! The matchbox favors were a big success! Someone would pay me to do that for a living — right?

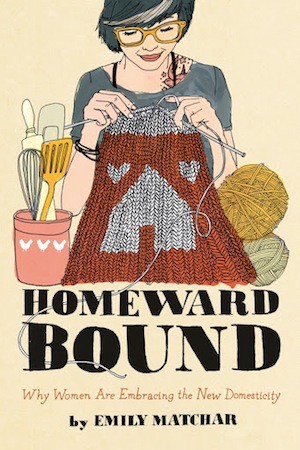

Wrong, says Matchar. I was listening to the siren song of the New Domesticity. In her new book, Homeward Bound: Why Women Are Embracing the New Domesticity, Matchar examines the DIY trend in a variety of manifestations — Etsy culture, “mommy” blogs, backyard chickens, from-scratch cooking — and sees a retreat to domesticity at the heart of it all. Homesteading, homeschooling, homemaking — home, home, home. The promise of the New Domesticity is that by circling our wagons and “doing it ourselves,” we can compensate for the lack of stability and work-life balance in the workforce and the failure of the government to ensure safe food, high-quality education, and sustainable environmental practices — all while making cool stuff! Moreover, Matchar is troubled by the way that this trend affects women economically, encouraging them to give up financial independence while breathing new life into old ideas about what women’s work should look like.

Matchar herself is no stranger to the pleasures of the New Domesticity (ask her about canning!), and she avoids judging its proponents, bringing a quippy, self-deprecating sense of humor to her topic instead. We recently spoke to Matchar about her book and the gender politics of DIY.

What makes New Domesticity “new”?

New Domesticity, the way I define it, is the re-embrace of old-fashioned domesticity by people who have the means and the wherewithal to not be doing this stuff if they didn’t want to. So it’s not the poor stay-at-home mother who is making her own bread because she can’t afford to go to Walmart — which doesn’t even make sense, but you know what I mean. It’s not somebody who has to be doing this because of poverty or because they’re in a developing country where they don’t have better methods. These are people who are embracing this out of choice, because of environmentalist, political, or at the very least philosophical motivations.

What’s wrong with retreating to the home? How is that potentially damaging to women?

The danger is that we want to have women in public life as much as we have men in public life, and if women are retreating, pulling back their participation in the workforce because the workforce is not meeting their needs, then the workforce needs to meet women’s needs. I think this is a sign that something needs to be done. I’m interested in the structural reasons why people are choosing this, and how we can make it so we can more easily blend domestic stuff and work, because I think we’re realizing, rightly, that there’s a lot of value in taking care of your family. And that should be something both men and women should be able to do alongside their jobs, and not have to choose in an either/or proposition.

You talk about the aesthetic aspects of DIY and the New Domesticity. What is it that makes it so compelling, outside of the dissatisfaction with work?

There’s a lot of beauty to be found in handmade stuff. We’re at a moment where we’re appreciating that aesthetic. One of the reasons that aesthetic is popular right now is it does represent — how to put this? It represents luxury, in a way that factory-made used to represent luxury. A hundred years ago, factory-made represented that you could afford it, that you didn’t have to make it. And now things have shifted so that mass-produced is cheap and homemade is expensive, because it means that you have the time to make something by hand — or at the very least, you have the money to pay somebody to make it by hand, and that represents a new luxury. I think that’s part of the reason we find it attractive, and why it has become so trendy.

It’s so adorable, all those little owls and things . . .

I know! And it took 25 hours to make!

I love the part where you mention corporate retailers co-opting the look of DIY.

Yeah, you can buy faux DIY, faux handcrafted stuff at Walmart these days, that’s how popular it is. So what does that say?

Thinking about quilt-and-sampler aesthetics, it seems like there’s always been some kind of undercurrent of nostalgia for that. What makes our craft aesthetic different from the craft aesthetic of even 15 years ago?

There’s always been people who did crafts, there’s always been Michael’s. I think the difference now is that it’s become cool for young people, and the aesthetic has shifted such that it appeals to twenty- and thirty-somethings rather than exclusively to your grandmother. That has a lot to do with old-fashioned retro stuff being reclaimed in a kitschy way — sort of how the Riot Grrls started reclaiming very stereotypical feminine tasks like needlework, but in this very winky-winky way, doing needlepoint pin-up girls, using it to make a statement. I think that really paved the way for crafts to have this renaissance that’s cool and hip and young.

Do you think there was a measure of irony there at some point that is now lost?

When this resurgence first happened, it was very politicized. It was very much about being anti-corporate, and reclaiming old fashioned women’s work in the name of feminism. But once that stuff became so hip and so big, with a million vendors on Etsy and hand-crafty stuff at Walmart, it certainly lost its political edge, and many people are embracing it as cute rather than political. And then there’s the danger that, if all this retro 1950s stuff is embraced as cute in a totally depoliticized way, are we actually then embracing the gender norms of the 1950s? There’s some show on TLC called “Wives with Beehives,” and these women in LA were doing the whole 1950s retro housewife look as a lifestyle. There are so many people doing that as a hipster thing, as “I’m a feminist burlesque dancer,” but these women seem to have very little sense of irony about it. Of course TLC may have edited all the irony out, but these women were like, “I serve my husband.”

You’re very respectful of all the subcultures that you venture into, but I can also sense your discomfort at different times in the book. Were you ever particular disturbed or disheartened?

There were two things. One was that a number of people I talked to seemed to have a skewed idea of what the feminist movement was. That is completely understandable, because the feminist movement is wrongly portrayed pretty much everywhere. So I think it’s understandable why women now are like, “Oh yeah, feminists, they said everyone had to get a job, and that ruined home cooking, and they disrespected stay-at-home moms.” And that’s just — that’s not accurate. It’s disheartening that so many people have been fed that wrong portrayal of feminism. That bugs me. And two, I was bugged by — a lot of this New Domesticity is very worshipful of all things it considers “natural.” And that can be anti-intellectual, and it can be, as I point out in the chapter about parenting, even dangerous when it comes to health and food stuff. The number one thing that bugs me is the anti-vaccine people. Again, it’s understandable how they reach those conclusions, because there’s so much cultural valorizing of the natural. You go into the grocery store and they’re talking about “natural” and “unnatural,” and you have idiots on TV that are Oprah’s gurus or whatever questioning mainstream medicine, and people get it in their heads that it’s good to be skeptical about medicine, that it’s good to have a DIY attitude to your own health. Which to some extent it is — it’s good to be informed. But it goes way too far.

One of the most surprising conclusions you came to was that while New Domesticity seemed to be associated with privilege, it was ultimately affiliated more with middle class culture than wealthy culture.

My feeling was that people who are actually members of the elite don’t need to be doing this stuff. They’re more satisfied with their jobs, because they have high-level, money-making jobs they’re less likely to abandon or cut back on. They have the kind of money that means they can negotiate work-family stuff. They can get a really good nanny, or they can buy all of their food pre-made at Whole Foods if they’re so worried about where it comes from. There are just less problems navigating work-life issues when you’re a member of the super-elite. It was mostly a movement of people that were middle class and that were feeling really stuck, feeling unable to balance work and life stuff, and feeling dissatisfied with their job opportunities.

There’s a term called “values stretch.” It means making a choice under duress, and then back-narrating it in order to show how you always wanted to make that decision.

That’s absolutely true. There’s a degree to which this New Domesticity helps people justify and feel good about the choices that they basically had to make. A lot of women are pushed out of the workforce, and nobody wants to feel like they’re a pawn, nobody wants to feel like they don’t have any power. I think a lot of the talk of opting out is more about being pushed out by some combination of forces. Women are encouraged to take that on, and say it was just their choice, which is something that benefits the corporations. If women are just choosing this, they don’t have to work harder to make better policies to keep them in the workplace.

You end the book with a list of recommendations. I wish you would just touch on the most important ones to you.

The important ones to me are, one, to continue to encourage men in the domestic realm and encourage men into more equal, sharing relationships in the home. Because women are fully encouraged to go for it in the workplace, and I think there’s less encouragement of men to take on traditionally feminine roles. There’s a lot of bluster about the “new stay-at-home dad”, but stay-at-home dads are only 3% of all stay-at-home parents. I think stay-at-home dads still face a lot of sexist prejudice, and that needs to stop. And then, two, rather than retreating entirely, just beating on corporate culture to change. Because people need jobs. Most people can’t not have jobs. Most women are going to work, most women want to work. And I think the corporate culture is waking up to this somewhat, but I think we need to keep beating on that. And then governmental policies. I still want to see universal daycare.

Crossing my fingers. What’s the craziest DIY project you’ve ever made?

When I was in my early twenties I stenciled and painted my microwave with a frog pattern, because I thought my microwave was ugly. Actually I think a friend of mine still has it in her house. That’s not extremely difficult, more just weird.

Was it fulfilling? Did it give you a sense of pride in your microwave?

It did! I loved that microwave. I loved my frog-print microwave.

Amy Gentry is a writer and performer living in Austin, Texas. You can find her writing about gender politics and literature on The Rumpus, the LA Review of Books, and her blog, The Oeditrix.