An Old Hollywood Chat with Emma Straub and Laura Moriarty

by Anne Helen Petersen

So first things first: can each of you give a short little spiel about your book? Like the one you give your mom’s friend when she asks “what have you been doing with the last two years of your life?”

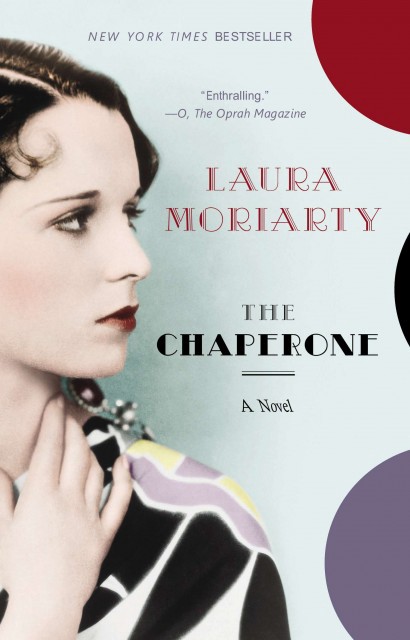

LM: I was reading a biography about Louise Brooks, the beautiful silent-film star with the black bob and bangs, and I learned that in the summer of 1922, Louise, then just fifteen and living in Wichita, travelled to New York City to audition for a famous dance company, and that she brought along a thirty-six-year-old Wichita housewife acting as her chaperone.

I felt immediate pity for the chaperone because out of all the rebellious flappers of the Twenties, Louise was the real wild one, and she wasn’t exactly known for being kind or docile. Not much is known about the real-life chaperone — after that summer, the chaperone when back to Wichita and lived out her life in anonymity while Louise catapulted to fame. I decided to completely invent a chaperone, with her own history and conflicts, while sticking to the facts of Louise’s fascinating life, and imagine the story of that summer and beyond.

ES: Ha, yes, I love that question. In my case, it feels a little bit like, “What did you do with the two years of your life before the last two?” — because, as many people know, it takes about a year for a book to go from manuscript to printed form, and then another year to move to paperback, which is what is happening now. But to answer your question, Laura Lamont’s Life in Pictures is about a girl from Door County, Wisconsin, who moves to Hollywood in the late 1930s to be an actress. The book follows her for the next fifty years, so it’s really her life story. Lots of ups and downs, of course, and lots of good dresses and feathers and parties.

I write Scandals of Classic Hollywood here at The ‘Pin, but I got into star scandals almost by accident, when I took a class on Hollywood stardom during my first year of grad school. What’s your story?

ES: I LOVE your Scandals of Classic Hollywood series so, so much, and have no doubt that you know 700 million times as much about Hollywood than I do. That’s the secret truth of my novel, I think — even though it is set in Hollywood, and in the crumbling studio system, that’s really just the backdrop for this one woman’s story.

Anyway, to actually answer your question, I came to writing this book through Jennifer Jones’ obituary. I was working on something else at the time, a novel that wasn’t going anywhere, and I read her obit and thought YES. That is a novel. It just seemed so dramatic and juicy and sad and wonderful.

LM: I love your column too. I got particularly interested in Louise after reading Flapper, a fantastic nonfiction book by Joshua Zeitz. He gives the tumultuous biographies of all the famous flappers, but he also discusses what they were rebelling against. Here’s what he has to say about the preceding generation’s corset: “The pressure it applied to women’s bodies averaged twenty-one pounds but could reach as high as eighty-eight pounds. Tight-lacing was thus akin to crushing oneself slowly from all sides.”

As a writer, I was particularly interested to how much was changing in 1922, for fashion and all it represented, and how those changes might feel to someone who had already come of age under an entirely different set of rules. My chaperone heroine, Cora, is pretty thoughtful, but Louise and New York overwhelm her for a while.

What did your research process look like? Did you watch a lot of movies, go to the archives, read trashy star bios? Tell us everything; we’re big research nerds here.

LM: Oh yes, I researched. I read Louise’s biographies and her memoirs. I read a tour guide to New York City of that era. I found clothing catalogs from 1922, with pages devoted to corsets and descriptions and prices for various hats. I researched cars, train travel. I read oral histories of survivors of the Orphan Trains (it figures into the story). I watched Louise’s most famous film, Pandora’s Box, up on a big screen at a silent-film theater. I read over reviews of 1922 Broadway shows, and I read lots of Ladies Home Journal articles from 1922. I found a ‘Best of 1922’ CD and played it, which made my daughter crazy; I have to agree the pop music of that era is a little like nails on a chalkboard. But I wanted to get the feel. I drove down to Wichita and walked around the old train station from which Louise and her chaperone really did disembark for New York that summer. It’s boarded up now, so I couldn’t go in, but just being there helped me understand the story and the people as real.

ES: Ooooh yes, all of the above! I took a few trips out to Los Angeles and went on studio tours, stuff like that. I spent a lot of time at the Margaret Herrick Library there, which is run by the Academy of Motion Pictures. What a phenomenal place. And yes, of course, I went to lots and lots of old movies. The best research one could hope for!

Laura, your book is (mostly) set in 1922, several years before Louise Brooks became a star, when the “New Woman” was causing all sorts of gender anxiety — anxiety that serves as one of the guiding narrative thrusts of your book. We have so many cliched representations of “New Women,” and they’re often mistakenly conflated with the Flapper. How did you conceive of the characters of the young Louise Brooks and Her Chaperone negotiating these new gender roles?

LM: I knew from the start that although I was interested in the tension between generations of this era, I didn’t want it to be a story of “young, progressive flapper shows old fuddy a new and better world.” My chaperone, like many women of her generation, fought hard for suffrage, and she’s a little dismayed that the new generation of women, simply handed the right to vote, don’t seem to appreciate it.

Cora also observes, quite correctly I think, that there are all kinds of corsets, psychological as well as physical, and that the new generation maybe just traded in one for another. At the same time, Louise, sometimes unwittingly, does challenge Cora to reconsider her views on morality and what it means. Cora is, first and foremost, a compassionate person, and in the end, that trait helps her transcend her generation, and it serves as her compass more than anything.

Totally second wave feminists pissed off at postfeminists — I love it. As a follow up question, what do you think this book, with its meditation on changing women’s roles and the freedom and anxiety that attended them, has to offer contemporary audiences? Put differently, what does a story of two women of different generations in the 1920s teach us about today?

LM: Well, a lot of those tensions haven’t left us. There’s a scene early on in the book where a misguided Cora tries to teach Louise the value of virginity, and she compares a non-virgin to candy that’s been unwrapped — she’s basically saying that men don’t want something dirty, not for marriage, at least. She has no idea what Louise has suffered and survived in her young life, and she has no idea how harmful her words are, not just to Louise, but to young women in general. Unfortunately, I didn’t get Cora’s speech from my research on 1920s. I got it from a 2010 abstinence-only lesson on sexual purity.

But I do think tension between generations is always with us. I read a diary of a Kansas housewife from the 1920s, and she seemed like a nice person, but she was scandalized that even women her age were starting to show their knees — she thought it looked vulgar. There are certain fashions now that to me seem a little vulgar, and that helps me understand the mindset of that Kansas housewife. La plus ça change and all that!

Emma, I get such a Greer Garson meets Norma Shearer meets Jennifer Jones vibe from the character of Laura Lamont. She’s married to an executive, she plays a very particular type of onscreen role that those first two, in particular, played throughout the late ’30s and ’40s. Yes? True? Tell me more!

ES: Yes. As I mentioned above, Jennifer Jones was my jumping-off point. I wanted to be really careful not to write the book as a sort of roman a clef, though, because that seemed so much less fun than playing with my imagination, so I purposefully stayed away from learning anything more about Jones. There were other historical figures who snuck their way in (Lucille Ball, Irving Thalberg) simply because I loved them too much.

When people think studio-controlled star makeover, they usually think blonde hair. I love that you have Laura’s hair dyed brown — which would’ve been totally historically accurate, as the platinum blonde craze was thoroughly outmoded by the late ’30s. Did you feel a responsible to be faithful to those sorts of historical elements? Were they liberating, or could they make you, and the story, feel trapped?

ES: Thank you for giving me credit for that! In truth I made Laura a blonde because she was from Door County, Wisconsin, and Norwegian. Those are my people, and my people are almost all blonde! So it just made sense that in order for her to have a transformation, it would have to be light-to-dark and not the other way around. I tend not to be an obsessive person, so I was totally fine with doing things as my story needed, and not worrying so much about the historical accuracy. I think that’s the key with writing a historical book — you want to know enough to have the book feel true, but not so much that you’re weighed down by the research.

For both of you — when I first started writing my scandals pieces, I was amazed by the outpouring of support and curiosity. Given the success of both of your books, do you think there’s a revival in interest in Classic Hollywood? Or does this stuff just never stop fascinating us?

ES: I think people love Hollywood, and have always loved it. The internet is amazing for offering us access to things we would have to search to find otherwise, I think that’s the big difference. Now you can read your column, or follow vintage Hollywood Tumblrs, and see pictures of Carole Lombard all day. It’s a beautiful world.

LM: I agree, Emma. It’s hard not to look at those old movies and photo stills and not see an alluring glamour and elegance. But I always have this desire to imagine those stars in color — not colorized, but in real life, off set, living their lives when they weren’t picture ready. The old movies have such a sheen, but there’s not a hair out of place, and it makes me want to look just under the surface and find the real lives and worlds underneath.

Last Question and a Very Important One: Favorite Classic Movie Stars (Male and Female) and Favorite Classic Film.

ES: I feel like I should have some cooler, more obscure choices, but my all-time faves are Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn, because they both do funny and serious and move their bodies in such incredible ways. As for favorite movies, Funny Face, Rebecca, Laura, Charade. Oh, I could go on and on.

LM: Bette Davis. Spencer Tracy. I hope this counts, because it’s in color: The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.

THANK YOU, LADIES. Now everyone else: go read!

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here. Her book, Scandals of Classic Hollywood, is forthcoming from Plume/Penguin in 2014.

Laura Moriarty is the author of The Center of Everything, The Rest of Her Life, and While I’m Falling. She was the recipient of the George Bennett Fellowship for Creative Writing at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, and is now a professor of Creative Writing at the University of Kansas. She lives inLawrence, Kansas.

Emma Straub is the author of the novel Laura Lamont’s Life in Pictures (out in paperback on July 2) and the short story collection Other People We Married. In addition to going to the movies, her favorite summertime activities are swimming in pools and eating fish tacos.