Dear Fred, Please Send the Money: In Need of Poetry

by Mairead Small Staid

In the fall of 2008, I spent ten days wringing every last drop out of a Eurail pass, sleeping on trains each night and walking around a different city each day. Day two found me in Bucharest. There the sky kept threatening rain, packs of wild dogs glared from weedy patches between the blocks, and a child tried to steal my camera from my pocket. For two days I hadn’t said anything but “please” and “thank you” to waiters and clerks, and I wasn’t sure I’d pronounced even those simple words correctly. The ornate buildings around me were covered in graffiti I couldn’t read. I was lonely. I was too hot in a coat I couldn’t take off, having no room for it in my stuffed backpack. I was tired of carrying a backpack, and beginning to regret my glamorous plan of training alone across Europe.

Then I saw English Bookshop: those most beautiful of words. I had packed only two books for my ten days, hoping to force myself into writing instead. The books were The Great Fires and Refusing Heaven, two slim volumes of poetry by Jack Gilbert that I’d already read and reread, loved and re-loved, many times in my life. As I moved through unfamiliar space, I remembered:

Walking in the dark streets of Seoul

under the almost full moon.

Lost for the last two hours.

Finishing a loaf of bread

and worried about the curfew.

I have not spoken for three days

and I am thinking, “Why not just

settle for love? Why not just

settle for love instead?”

– Jack Gilbert, “Not Getting Closer”

But I needed more to get me through — and I found it in a tiny, tidy, white-walled shop tucked around a corner in downtown Bucharest. Fifty Romanian lei bought The Paris Review Interviews: Vol. 1: sixteen authors were exactly the company I needed. Among them, second from the end, was my old friend Jack Gilbert, with the latest installment in our long conversation: new words I could devour and survive by.

*

A couple months ago, I snagged the best seat (bar’s end) at my local pub for an evening of trying to write. Noticing my notebook, the man two stools over asked if he could give me a copy of his literary journal. The journal was Unsaid and the man was David McLendon: editor, writer, earnest lover of literature. When I confessed that I wrote poetry, mostly, the first words he said were, “Do you know Jack Gilbert?”

I did. I had just reread:

Are the angels of her bed the angels

who come near me alone in mine?

Are the green trees in her window

the color I see in ripe plums?

If she always sees backward

and upside down without knowing it

what chance do we have? I am haunted

by the feeling that she is saying

melting lords of death, avalanches,

rivers and moments of passing through.

And I am replying, “Yes, yes.

Shoes and pudding.”

– Jack Gilbert, “Say You Love Me”

David told me stories about Gilbert in recent years, before his death in November, when the dementia meant he didn’t know his own poems. “Did I write that?” he’d asked, at a reading in his honor. David told me about seeing Gilbert at the 92nd Street Y, where he almost walked off the front of the stage — a long drop — but the raised arms of the crowd kept him safe. And David later sent me a 1962 interview that Gilbert had done with the editor Gordon Lish, one that had somehow slipped by me despite my many years as an acolyte. From my old friend, new words:

An awful lot of the poems I see published remind me of the correspondence between Marx and Engels. Engels was always writing elaborate letters filled with ingenious, painstaking comments on Marx’s theories equating them mechanically with some current scientific thought. And Marx (or the reader) kept writing back, Dear Fred, please send the money.

*

Recently, my boyfriend went to a poetry reading. “How was it?” I asked. “Hipster,” he replied, “You would’ve hated it.” He polished his enormous glasses on his plaid shirt before settling them on a face graced with scruff. He wanted poetry about things that couldn’t simply be said, he said, and I remembered Gilbert’s shortest poem, the tongue-in-cheek “Métier” — “Greek fishermen do not / play on the beach and I don’t / write funny poems.” I remembered his quip in the Paris Review interview: “I like it when people talk about things.”

Things, for Gilbert, are love and death and little else. Things are the sustenance of a familiar voice in a foreign country, the sweetness of connecting with a stranger, of urgency and unfettered need. Dear Fred, please send the money. If you too are in need (and maybe you’ve already devoured all that Gilbert’s written) here are a few more poets who will meet you where you’re standing:

Richard Siken, Crush.

In her introduction to this 2004 winner of the Yale Series of Younger Poets, Louise Glück compares the book to Sylvia Plath’s Ariel. Not convinced? Read this and this and this and then trust me when I say that the whole collection is just that good, even better. Tell me how all this, and love too, will ruin us. / These, our bodies, possessed by light.

Rebecca Lindenberg, Love, An Index.

This is the first poetry collection from McSweeney’s and man, does it make me glad they came around to the idea. Lindenberg’s exquisite debut is haunted by Craig Arnold, another wonderful poet and her partner, who disappeared while hiking a volcano in Japan in 2009. At a reading, she called these poems “an extension of the rich and wonderful conversation we had… me picking up the phone and calling him, even though he can’t answer.” Get a taste here and here, where she queries the gods: send me a word for faith / that also means his thrum, his coax and surge / and her soft hollow.

Eduardo C. Corral, Slow Lightning.

2011’s Yale Younger winner and a volume of unending grace. The body breathes throughout this collection, whether heavy with wounds or light with ecstasy. Sex, death, family, religion: all the good stuff is in here, tempered by language’s steel. The strength of this poetry belies its own claim: The heart can only be broken / once, like a window.

Mairead Small Staid is a little bit country, a little bit rock ’n’ roll. Her work has earned her residencies at the MacDowell Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts, as well as publication in The Southern Review.

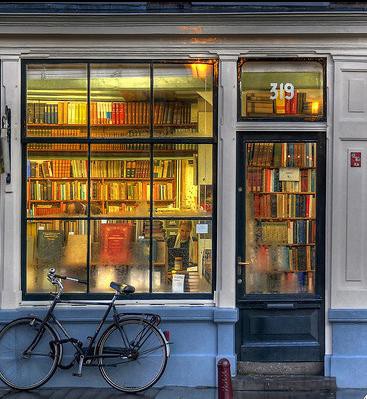

Photo via llibreria/flickr.