The Source Family: A Cult I Might Have Joined

by Alexandra Molotkow

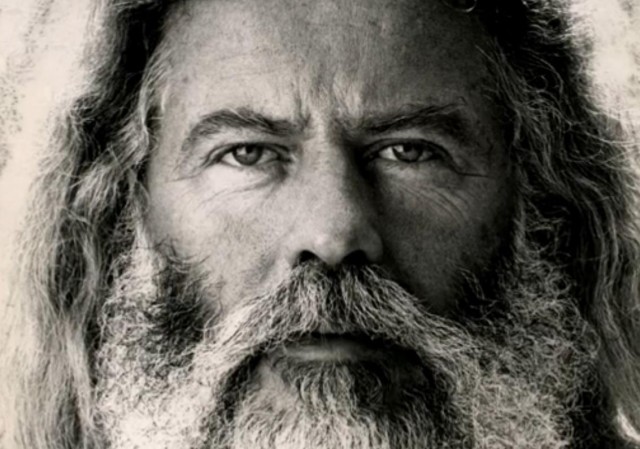

What would you do if a middle-aged man with a big white beard and a long white robe asked you to be his daughter? What if he had a magic touch that made you forget your name, and he smelled like a blend of rosemary and river mud and deep BO pheromones,* and he owned a successful vegetarian restaurant with the best salad dressing in all of Los Angeles? If anything, you would use protection and then shudder off the oxytocin rush. But if this were the ’70s, and you were a wandering hippie in search of a higher purpose, you might join him in his mansion in the hills and call him Father Yod. I would not judge you. [*This is speculation]

The Source Family was a spiritual collective — a cult, if you will — of about 140 members, most of them under 30, most of them great-looking. They ate raw food and home-schooled their home-born children; they dressed in beautiful robes and sometimes ate at Chasen’s, where Father Yod would bribe the maitre d’ to seat them next to Ronald Reagan. Father, who cruised around town in a $34,000 Rolls Royce, was keen on “nice things” for the “life trip” and believed that money was “magical green energy that will produce anything for you instantly.” He did not believe in hospitals.

I know what you’re thinking, but it’s not like that. (Actually it is, but there’s more to it.) Father Yod led his family through a life of heavy enlightenment and rigorous hedonism: 4 a.m. meditation sessions invigorated by “Sacred Herb,” sex magic in which men “withheld their seed” (or tried to), as well as psychedelic jam sessions resulting in some very collectible records (and a few memorable performances, including a concert on the lunch patio of Beverly Hills High School in 1973). Lots have been reissued over the years, sparking new waves of interest in the Family and its New Age idyll, and last night a documentary on the Source Family premiered at the IFC Center in advance of screenings nationwide. It follows a book by Isis Aquarian, the Family Historian and Keeper of the Records, with help from Electricity Aquarian, who maintains an intense beard to this day. All of their last names were (legally) Aquarian. Their middle names were “The.”

Before Father Yod was Father Yod, he was Jim Baker, a judo master and decorated Marine. In the early 1950s, he abandoned his first wife and daughter to ride to Hollywood on a motorcycle and audition for the role of Tarzan. He didn’t get the part, but here are some things he did instead: kill a man, in self-defense, with judo chops; kill a man, in self-defense, with either judo chops or a gun; marry and eventually leave a second wife, Elaine, with whom he’d had three kids and a spiritual awakening; cure a Samoan tribal chief’s ailing daughter through dietary remedies, marry, then leave her; rob “between 2 and 11 banks” to fund his health food restaurants, which were very successful. (Some of these feats are documented; others he only recalled to his spiritual children, in the third person, since the Baker trip was done by then.)

In April 1969, Baker opened the Source Restaurant on Sunset Boulevard, where, on a given day, you might find John Lennon or Joni Mitchell scarfing alfalfa sprouts. There, he met a new wife, a 20-year-old named Robin Popper (he was 47), and began holding meditation classes for a growing group of devotees. A spiritual clique began to form, and in 1972, Yod moved everyone into a 15-bedroom manor in Los Feliz. At the “Mother House,” he got way into playing the dad many of his followers never had — tough, loving, exciting, and wealthy — and his “children” thrived in the warm musky glow of his wisdom.

Family life was often blissful, but often intense, and sometimes just dark. According to Omne Aquarian, interviewed in the film, certain magical practices created a “rent in the astral world” and people saw vampires hanging out on the staircase. Dating was complicated: Women chose their partners — for whom they sewed robes, and made coffee, and gave “skilled massages” — but could be “reassigned” to “single sons” according to the dictates of Father, who retitled himself YaHoWha to indicate his godliness. While initially faithful to Robin (Ahom, the Family’s Mother), his eye wandered to a 19-year-old named Susan (Makushla), who remained his Mother/Angel while he accumulated 12 more “spiritual wives.” Robin, in the film: “He might as well have skinned me alive.”

When their lease wasn’t renewed the following year — the LaBianca murders being fresh local history — they found a place closer to the Source Restaurant and called it the “Father House.” Since it was smaller, most had to sleep in stacked cubby holes, which was not copacetic to the authorities. Neither, at the time, was home schooling, or home birthing, or letting kids with bad infections go without medical treatment. When a Source Family baby nearly died of staph in the lungs, the hospital reported them. Soon after that, the Family teachings got deep into apocalypse.

In the fall of 1974, Father announced he was selling the restaurant and moving the Family to Hawaii. “We all sat in shock as he talked about it in the mornings,” Isis writes. “But he would talk for what seemed to be hours of the wonderful fruits that we would soon enjoy in Hawaii and yell, ‘HMMMM!’ after describing each one in detail. Lychees! Mangos! Coconuts!” For a year or so, the Family wandered as their money dwindled: first to Kauai, where the locals despised them; then to San Francisco, which was pricy; and finally back to Hawaii. There, in August 1975, YaHoWha made the fateful decision to hang glide without a lesson. While nobody says this outright, one gets the impression that he was testing himself: If he were God, he would soar, if he were a man, he probably wouldn’t. “I thought that I was going to fly the kite,” he told his children, after landing hard against the beach. “But I guess it was God’s last lesson. He had to teach me.”

Yod did some highly condemnable things. He abandoned partners when it suited him and fucked with girls young enough to be his biological daughters — “I feel like still,” Makushla says, “to this day, I work with not giving my power away to another.” Babies, as well as adults, got dangerously sick and, in at least one case it seems, died without receiving hospital treatment. You can’t really defend any of that, and not all of the Source members interviewed try to: Most seem to remember him fondly, but critically. Lots count the Source Family years among the best of their lives, and only a few say they’d never do it again. Yod is remembered as a Cool Dad. Even Cool Dads can be bad.

Dying might have been the best thing Father Yod ever did for his children. He left the body before things could go too far south, and let most of his followers get on with their lives, though it’s hard to forget Robin weeping next to his picture. The Source experience was total, but ephemeral — a cult, but not one of those killer cults. You find yourself falling hard for the whole experiment, then fighting hard not to yell at the screen. But you leave thinking it might’ve been a far-out way to spend your 20s, considering how most of us spend our 20s.

It feels okay to see the Source Family as kind of a great fantasy, as much now as it was then. Hip 20-somethings don’t really join cults anymore; everyone knows too much to buy into one guy’s idea of utopia. But I think most of us get that yearning, from time to time, for some benevolent overlord to make sense of the world for us. There are people I have exalted as Better Than Me and would have handed my brain over to if they’d deigned to accept it. If my twelfth-grade philosophy teacher had told me to throw out my Polysporin, I might have. Had a certain professor held early-morning economics lectures out of his townhouse, I totally would have gone, and if he’d wanted me for a spiritual wife, I think that would’ve been groovy for about a year. I still like the idea of someone who has all the answers; I just know now that no such person exists.

Furthermore, life in the world of provable phenomena gets dull. There are only so many colors in the spectrum and there are only so many ways to have fun at the bar. If some grandiloquent Santa promised me new colors, plus secret wisdom handed carefully down through the ages, plus a variety of mind-bending experiences — well, I’d love that. But I’d worry about dying or sustaining permanent brain damage. And I’d feel ridiculous at Chasen’s in bare feet. And I couldn’t suppress the knowledge that no human being should have that kind of power over anyone else.

In short, I want to believe. But I can’t. But I loved the movie.

Previously by this author: Talking to My Exes Exes

Alexandra Molotkow is a writer and senior editor at Hazlitt Magazine.