Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Robert Redford, Golden Boy

by Anne Helen Petersen

Robert Redford still does it for me. He did it for me when I first saw him in Butch Cassidy, he did it for me when he was washing Meryl Streep’s hair in Out of Africa. He did it for me in uniform in The Way We Were and with full hippie beard in Jeremiah Johnson. He’s classically handsome — the type of handsome on which you, your mom, your grandmother, and your best gay friend can all agree — with a flatness of expression that morphs sardonic when you least expect it. He has a storytime voice, the perfect level of tan, and haphazardly spaced highlights that betray a life lived en plein air. I love him for his palpable Westernness, his ease with open spaces, the scent of high altitude that seems to waft from him. He looks as good in jean cut-offs as he does in a well-tailored suit. And for nearly 40 years, he’s been Hollywood’s golden boy: likable and bankable, if a bit self-serious.

Redford belongs to the class of actors I think of in my head as the silver foxes: indigenous to the ’60s and ’70s, they’ve ripened before our eyes. Most of them have semi- or totally retired, some have passed away; all live in my memory both as their original, gorgeous selves and their well-lined, refined later-in-life iterations. Newman and Beatty, of course, but also De Niro and Hackman, Dustin Hoffman and Jack Nicholson, Jane Fonda and Julie Christie.

They’re not classic Hollywood, per se. They never had to deal with studio contracts. They got to use their real names and marry whom they pleased. They shunned publicity, or at least pretended to shun publicity as they posed for the cover of Life. They were a different type of star, in terms of interaction with the industry at large, but stars nonetheless — embodiments of what mattered to Americans at various cultural moments. And Redford, I realize now, was proof positive that beautiful American men could still exist amidst the turmoil of the age. Turns out he was a bit of a true liberal, but at the time, he had the looks of a jock, the demeanor of a respectable man, and just enough zest to titillate. I can’t quite decide whether he’s a good actor or a perfect star — which, if you think about it, is true of the most memorable of our idols.

Throughout his career, Redford’s split critics: maybe he could act, but could he act other than himself? And isn’t that the very hallmark of a star? David Thomson called him a waste, while Pauline Kael understood that his golden diffidence was part of his allure, what drew us back to watch him over and over again. He never gave himself over fully the way that his co-stars did — not because he wasn’t acting, but because that was the point. He was, and remains, too cool. Which is part of why his enduring popularity is so surprising — is it his looks that bring us back, again and again? Or is the semi-masochistic desire to watch him maintain that aloofness?

Redford was born in Santa Monica, because of course he was. His father was a milkman but, in a page straight from the American Dream handbook, eventually became an accountant, moving his family to Van Nuys. There, Redford played on the high school baseball team and, if looks are to be believed, slayed the entire female population. A baseball scholarship to the University of Colorado followed, and I can just imagine him skamping all around Boulder, drinking beer and breaking hearts.

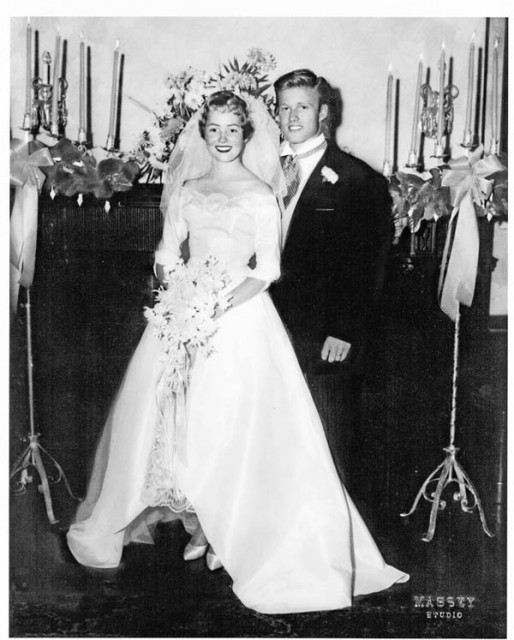

I mean, please. But he had better things to do than play beer pong, so he traveled Europe, took painting at Pratt, and eventually got caught up in acting, making his way into the live television scene in New York, which was thriving in the ’50s. At some point between flipflopping his way through Europe and going to Pratt, he married Lola Van Wagenen, whose native Utah he would gradually make his own.

The sidepart, the beautiful sidepart!

Despite his boho attempts, the baseball/jock thing would structure his image moving forward. He guested in everything from Alfred Hitchcock Presents to The Untouchables while also working Broadway, hitting it big with the lead in Neil Simon’s Barefoot in the Park (1963), which ran for an approximate eon.

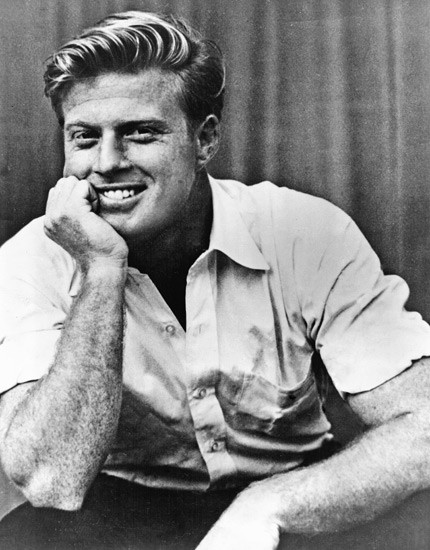

In his first publicity shot, circa 1962, you can already see the crinkle in his eyes that made him seem more sophisticated, less fratty.

There were bits and pieces in Hollywood — with Sydney Pollack, who’d prove his long-term collaborator, in Warhunt, and playing a bisexual, his only truly risky film role, in Inside Daisy Clover. He won “Best New Star” at the Golden Globes, but at the time, that was (almost) like winning the same award from The People’s Choice Awards — publicity but totally silly. This Property is Condemned was his breakthrough, complete with a serious soon-to-be-all-star line-up. Syndey Pollack directing, Tennesse Williams’ on the source material, a very young Coppola on the screenplay, Natalie Wood as his co-star.

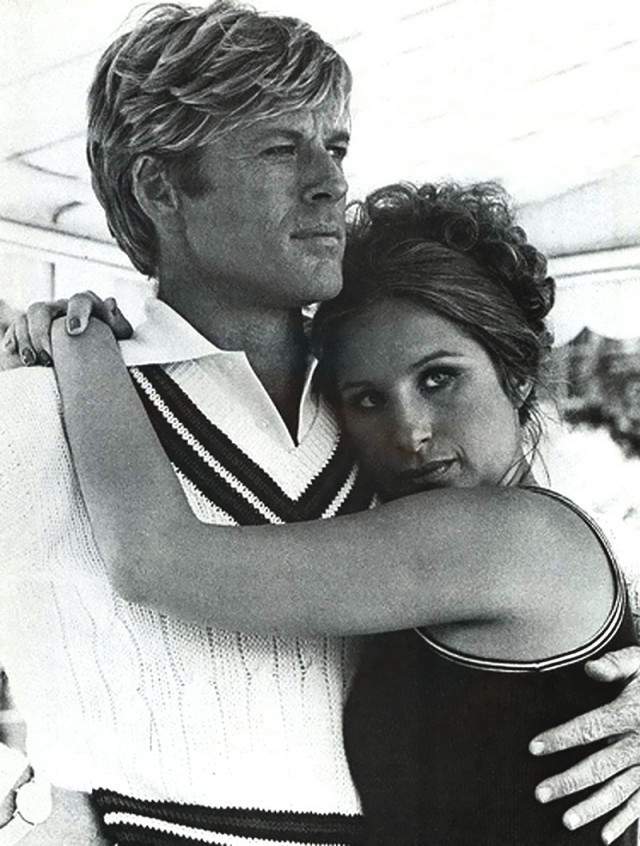

Just sitting around being beautiful people.

Wood is just so good at playing gorgeous poor people — there’s always been a wantonness to her eyes, it’s something to do with the way they do her eyeliner and the way she looks up at people.

You see what I mean?

The film, which focuses on a guy sent down South to administer lay-offs during the Depression, is a mix of Up in the Air and vintage Tennessee Williams, which explains why a weird incestual air imbues the entire production. But Redford establishes the distance and (initial) resistance to feminine wiles that would characterize the rest of his career. He’s lovely to look at, if not always lovely to his romantic interest. But I hope you see that that’s the charm: he’s a dick for the first half, and then he falls for you during the second half. Sure, he’s still a little aloof, but he just said he loved you, even if he was all straight-faced about it. Trust me; just run with it. Think of how beautiful your children will be.

He played second fiddle to Brando in The Chase, a film that strikes me as alternately hysterical and nearly perfect depending on the day. Jane Fonda was in the mix, too, and came back with him for the film adaptation of Barefoot in the Park. This was Fonda at the height of her va-va-voom era, when she was married to French director Roger Vadim and about to do Barbarella and take the world by storm. In Barefoot, she’s all high-waisted pants and long legs, the ’60s version of the manic pixie dream girl flinging herself around New York and upon the very supplicating Redford.

It’s a nice play on Redford’s fledgling image: he plays a reticent yet beautiful young lawyer; Fonda plays his very new wife, who loves to say inappropriate things, drag him to Staten Island for Albanian food, and have a lot of sex. When she realizes he’s kind of a bore, she decides to divorce him, at which point he gets drunk, becomes ridiculous, and proves to her that he can be awesome, too. There’s some weird, regressive rhetoric that runs through the script — Fonda’s mother tells her that a successful marriage is based on “making the husband feel important,” and it’s not a matter for satire. In hindsight, it sticks out as a film that wants to have it both ways: sexually liberated yet ultimately ideologically conservative.

Redford also looks somewhat tired throughout — maybe because, as the script implies but never shows, he’s having sex with Fonda six times a day. He’s stunning but bland, which, of course, is part of the point. But the last 10 minutes, the drunken fool minutes, are so delicious; it’s the dessert that makes him a star, as opposed to a handsome model for JC Penney. But Redford also understood that he had to get away from tightly-laced man-in-the-gray-flannel-suit characters lest the type consume him. He passed on The Graduate and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, opting instead for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

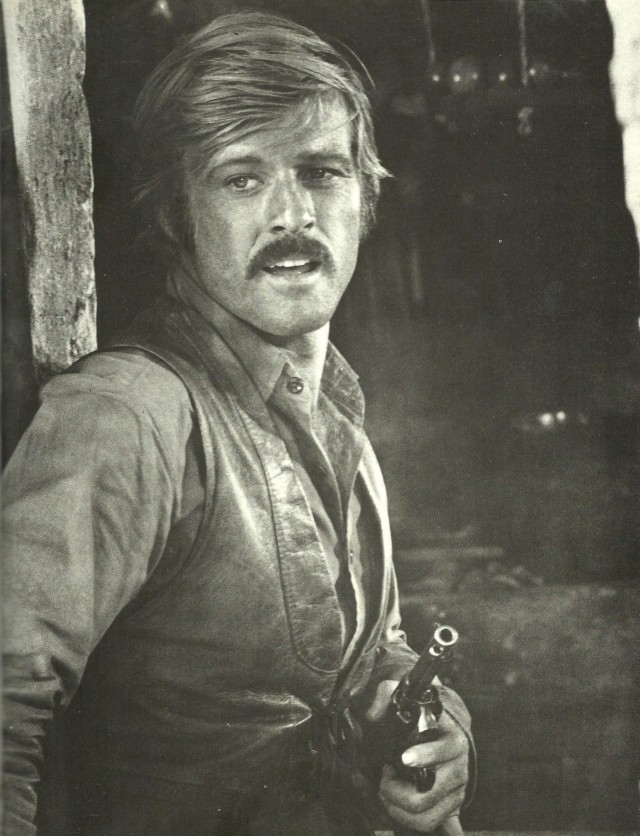

A moustache and cowboy hat covered the good looks and baby face, while a deep tan and some good wrinkles made him look about 10 years older. Now, I’ll say the same thing about this film that I did when I wrote about Newman: Butch Cassidy was counter-culture lite. It was released in 1969, but every time you think of the hippies and San Francisco and lots of sex, remember that the vast majority of America still just wanted to watch a Western with two palatable guys. Kael called it a “glorified vacuum” — a “facetious Western.” She’s totally right, but that doesn’t mean that it’s not still one of the most watchable filmic artifacts of the era. It’s also a prime example of two actors acting out their public images — Newman, as Kael points out, was the “aging good guy,” while Redford was still his removed, sardonic, handsome self, no matter how thick the moustache. It’s another reason the comparison between Cassidy and Ocean’s 11 is apt: both are glossy takes on the caper; both enlist stars to essentially play themselves.

Newman was already a star, oozing with prestige. Yet for Redford, the film’s mind-blowing success not only launched him into bonafide stardom, but marked the beginning of an associative pairing of the two. (Speaking of which — seriously, ladies — WHO is starting the FuckYeahCraggyDudes tumblr?)

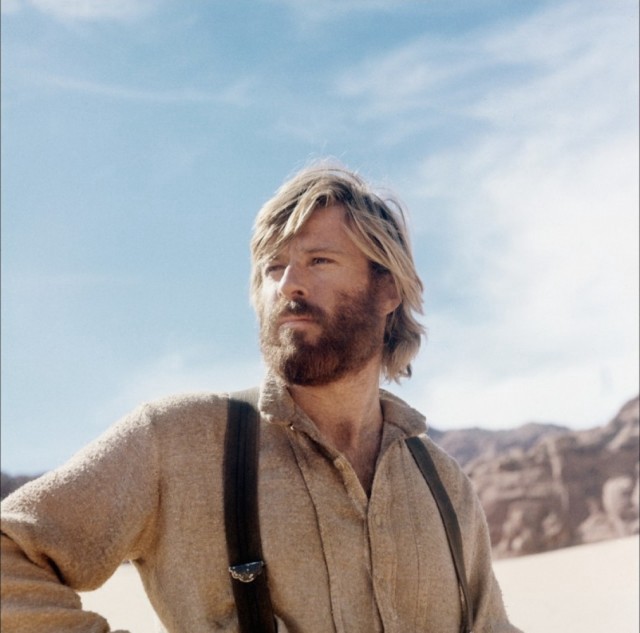

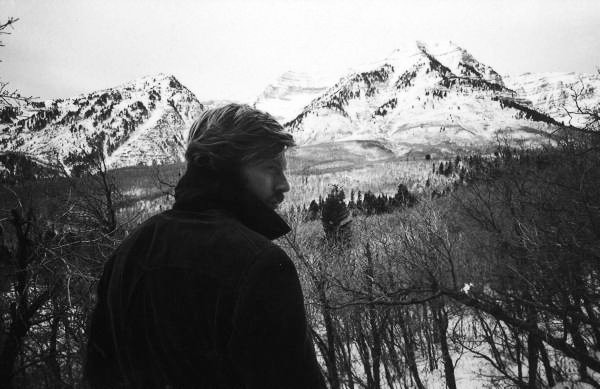

Suddenly, Redford could do anything he pleased, free to spend the Hollywood capital that comes with a monster hit. He produced and starred in Downhill Racer (essentially an exercise in looking hot on the ski slopes), first aired his political leanings in the very Kennedy-esque The Candidate, and did some serious beard acting as Bon Iver’s spiritual grandfather in Jeremiah Johnson.

Shearling Coats: Bring Them Back.

My backwoods boyfriend.

No huge hits there, but it didn’t really matter, because suddenly there was The Way We Were — and it was all anyone could talk about. It was like everyone finally recovered after Love Story just in time to ruin themselves again when Barbra sings the theme song. I feel like I was born with this song in my head and I didn’t even see the movie until my late 20s. And Barbra! I didn’t even get Barbra until I saw this film — well, this and Funny Girl. And everyone who’s trying to sell Lea Michele as the new Barbra needs to chill, because obviously it’s not about the singing so much as the persona.

Redford comes into the shop where homely Streisand works, and she’s all, “Look who’s here, America the Beautiful,” and you’re all, YES, TRUER WORDS HAVE NEVER BEEN SAID. But then you get suckerpunched by how effectively this movie convinces you that Redford would fall for Streisand, with all her spunk and unruliness and radicalism. The essential message of this movie is that Hot Guys Like Brains and Sass. The secondary message is that Your Romance Will Then Be Plundered By Asshole Red Mongerers.

Point is, Redford wasn’t just hot. He was a man who recognizes integrity — in Streisand and, by extension, in you. He was, at least in this role, the ’70s version of Feminist Ryan Gosling. And with moustache and mountainman beard gone, it was time for the No. 2 Most Handsome Man to rejoin the No. 1 Most Handsome Man and make another historical movie, this time with more suits.

The Sting is like Butch Cassidy but with more Joplin and nattier outfits. George Roy Hill directs again and Redford and Newman look ridiculously beautiful again (only this time Newman has stolen Redford’s moustache). Predictably, everyone and their grandma went to go see it, but what I love is that it was before the time of sequels — so instead of just rehashing the plot and adding a new villain, they actually had to find a new script, idea, and historical setting. The blockbuster sequel before the blockbuster sequel, and all the better for it.

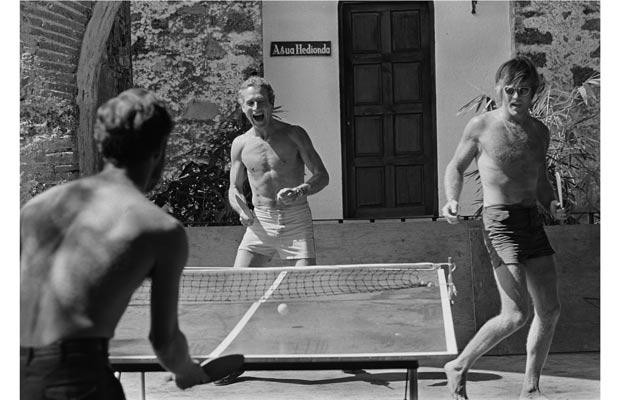

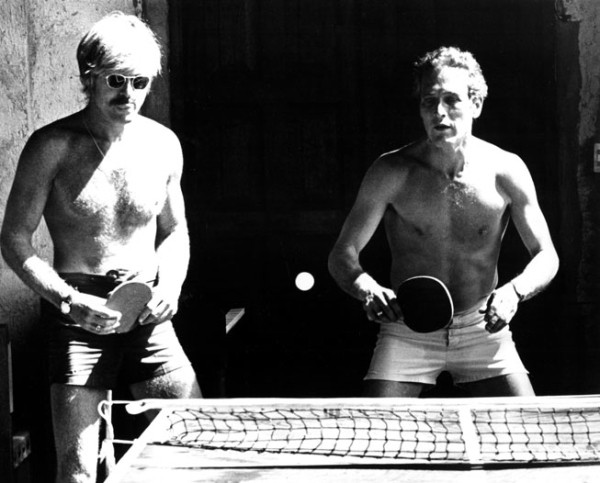

Plus you got to spend a bunch of time thinking about what the stars were doing behind the scenes: just normal bro-stuff like playing shirt-less pingpong in your cut-offs:

Oooo Robert, you and your aviators, run that game. Run it all the way to Cannes, where you can hang out with Sydney Pollack, presumably wearing one of my collared tees from 1996, and wear your own white velour half-zip:

But then there was the vast disappointment of The Great Gatsby — a film I wanted so badly to be perfect, and I’m sure so many others did as well, even when they weren’t just jonesing for some sort of film adaptation after reading Gatsby in 11th grade and still wondering what the green light REALLY MEANT I mean SERIOUSLY.

But this film offers no answers. It’s a classic case of They Did It All Right: the costumes are right, the casting is seemingly right, the set design is right. Redford, the most golden and All-American of boys, should’ve been right — a product of the American dream itself, a man who left behind his past for a brighter one. And Mia! Sweet, innocent-faced Mia.

Yet there’s a chasmic absence of soul. I realize that the plot is, at least in part, about a chasmic absence of soul, but you need the structure around that chasm to reverberate with life and tension and desire, the way (at least in my unpopular opinion) it does in Luhrmann’s adaptation. Because say what you will about Luhrmann, but his movies wear their hearts on their sleeves.

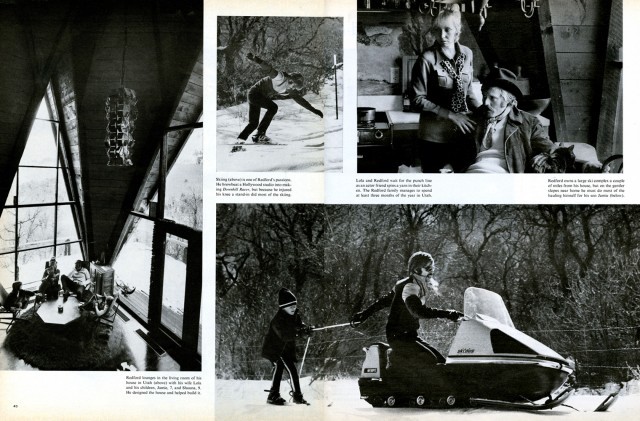

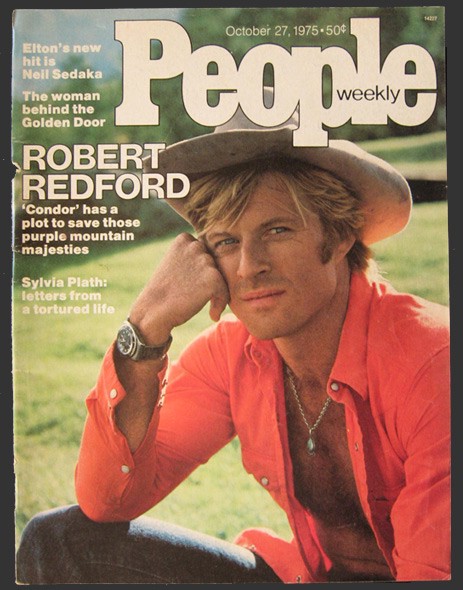

This Gatsby adaptation was empty, but that doesn’t mean that people didn’t still go see it. There was a compulsion there, in the same way there was with Les Miserables this past Christmas. Meanwhile, Redford’s image only continued to refine itself: after the success of Cassidy, the magazines couldn’t get enough of him. He was on the cover of Life and in a full-page spread, reveling in his Utah-ness:

Snowmobiles, moon boots, vaulted-ceiling wood cabins: give me all of them.

Whether in Seventeen, Redbook, Good Housekeeping, Life, or People — you name the popular publication — the message was the same: Redford wasn’t your typical star. He publicly hated publicity. He was “not an actor who acts how he looks,” which is just another way of saying he wasn’t an asshole. He “wasn’t in love with the sound of his own voice,” according to McCall’s, and regularly “[gave] cast members rides in his car.” He didn’t have a suit or a mansion, and he loved his wife and their four kids, whom he called his “best friends.” Robert Redford: He’s Just Like Us! Only with a better highlights and chest hair!

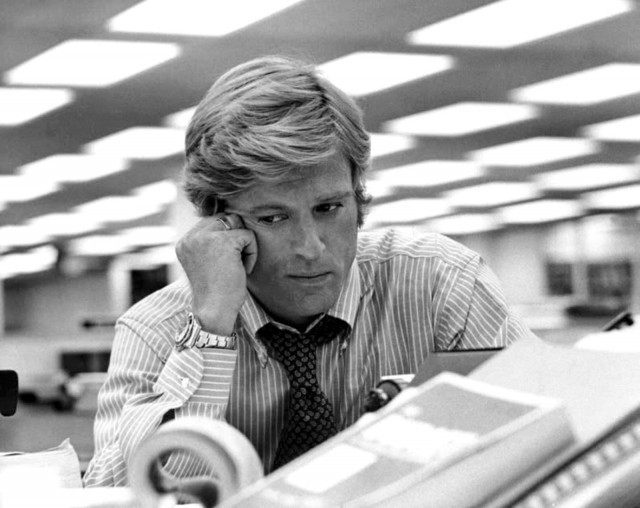

He was all CIA-conspiracy theory in Three Days of the Condor and very serious in All the President’s Men, arguably one of the most important and influential political films of all time. It didn’t hurt that he was just getting more handsome…

…and probably inspired the declaration of at least 100,000 journalism majors. It’s such a snappy, important picture — eminently watchable and built on the charisma of its two leads. Once again, the comparison with Clooney and his ilk is apt: they manage to make the political thriller sexy and electric while still maintaining its integrity. Redford spearheaded the production, adaptation, and editing process — an arduous process that would prepare him for his next natural role: director.

A few forgettable films in the late ’70s may or may not have prompted Redford to finally take matters into his own hands. He read Ordinary People, decided the project was his, bought the rights, shopped the project to Paramount, and promised a shoestring budget. Donald Sutherland, Mary Tyler Moore, and a veritable watershed of tears followed. Redford won the Oscar for Best Director, the first in a long line of testimonies to the Academy’s love of actors-turned-directors. I really have no comment for this film. It’s fine. It’s the sort of thing the Academy loves one year and forgets about the next, and it’s no Notebook, at least in terms of wringing me dry for tears. Like if you’re going to do the birds flying at sunset over the river, you’ve got to turn that knob to 11.

Directing Mary Tyler Moore on how best to make you cry.

If there’s anything that adds prestige to an actor’s image, it’s directing. (Just ask Ben Affleck.) But it’s even better if you can direct AND be a philanthropist. (Just ask Angelina.) So Redford founded the Sundance Institute in 1981 — it joined the Sundance Film Festival, founded in 1978 — consolidated operations in Park City, and used the hype over Ordinary People to draw attention to his various projects: cultivating fledgling filmmakers, funding underfunded documentaries, and turning Park City into a destination. There were many ins and outs that transformed a relatively tiny foundation into the indie behemoth that was Sundance in the late ’90s, and you can read all about them in Peter Biskind’s salacious and highly readable Down and Dirty Pictures.

Point is, Redford was becoming more than the sum of his cinematic past: more than a movie star, more than a beautiful face. Over the course of the next 20 years, he’d become something just shy of a mogul, at least in terms of perceived power and industrial cache. He wasn’t running a studio, but the most important American film festival — a festival that could make or break an aspiring director’s career — had his name on it. Or, at least, the name of his most famous character.

In the early ’80s, however, Sundance was still somewhat of a clusterfuck — lots of vision, little action. But that’s okay, because all anyone was actually thinking about was how much they wanted to move to Kenya and live in his tent:

I don’t want want to displace Meryl Streep in this movie so much as I want to hang out with both of them — or just watch them be wonderful together.

I guess I’m describing the act of watching any movie, but bygones. I want to watch this movie at all times. I fully realize it’s a commercial for Banana Republic. I fully realize the problematic post-colonial nature. I fully realize that it’s sentimental, but I am so OK with sentiment when it’s this tan and washing hair:

I first saw this film when I was in early high school and totally obsessed with a love that gives and takes — you know, the anguish of liking a guy, he kinda shows that he likes you, he retreats, rinse and repeat. I was also in a deep love affair with the book and movie version of The English Patient (“The heart is an organ of fire” asdf;kjasd;flkjasd;lkfja;sdjlf), so Out of Africa only doubled my obsession with texts centered on strong women and iconoclastic men. Set approximately 80 years ago. In Africa. The love in both of these texts is a very adult sort of love, but the way it makes me feel is pure 16-year-old. Those are the movies you return to again and again, to better remember the curves of rapture.

Out of Africa swept the Oscars, winning nearly everything and getting nominated for everything else. The only person left out was Redford himself. He was, in truth, the foil to Streep’s masterful Karen Blixen, the force that makes her real and alive. Plus he’s essentially playing the safari version of his existing image, and the Academy always prefers an accent or a Method turn to a masterful turn as yourself. The reticence, the side-part, the flat voice, the heartbreak — it’s all there, withdrawn and quietly aching, just like my heart at the end of the movie.

And then, the ’80s and ’90s: more films, more directing. Sundance expanded; Sneakers showed teenage me what a fun caper could do. And A River Runs Through It, holy shit, let’s talk about a movie making you fall in love with landscape: it was shot just over Lolo Pass from my hometown, and no film has done more to make me appreciate where I grew up. The fact that Maclean’s family was Presbyterian like mine only made it resonate more — I almost begged my mother to pull the “write it, now cut it in half” trick that Tom Skerritt pulls on his son. When Tom Skerritt showed up at my office door earlier this semester [LONG STORY] it wasn’t Top Gun that sprang to mind, but Reverend Maclean.

Brad Pitt playing Paul Maclean is clearly, deliciously, Redford’s aesthetic doppelganger. But it’s the other, more sensible brother — Norman, the author of the book and the voice of the film — who most aligns with Redford’s image. Where Paul is brash and wild, Norman is thoughtful, determined, and responsible. He lacks Paul’s gravitas, but he also lives to tell the elegiac tale of his brother’s self-destruction. He stood in the towering shadow of rebellion, much like Redford had lived through the counter-culture and kept his own centered sense of self.

Sweet dad jeans on the set of River.

Like so much of Redford’s work, A River Runs Through It relies heavily on the magic hour and lens flare, on golden morning light and the way it reacts with the skin and hair of beautiful men and their women. I can’t say it’s high art, but again, like so many of Redford’s films, it’s so watchable I can’t dismiss it. And so the rest of his films seem to go: Indecent Proposal, Up Close and Personal, The Horse Whisperer, Spy Game … genre fare, fairly forgettable. With Redford, it’s not the individual films so much as the overarching impact of his presence. And that’s the mark of an old-fashioned movie star — you don’t remember the plot as much as you remember the feel. The aura of greatness around Redford only continues to grow, and as the star becomes legend, it becomes clear that his death, whenever it comes, will likely beatify him once and for all.

Redford was a bonafide star when they were increasingly hard to find. Not all of his movies are masterpieces; indeed, most are just this side of pablum. But they’re also very good fun — the type of movie you’ll always stop and watch on cable, the type you can rewatch again and again. Don’t mistake me: I love these movies. They’re film at its most broadly entertaining, which is, really, Hollywood’s backbone. Redford unified the country in its affection for him when it couldn’t agree on anything else, all the more surprising given the gradual revelation of his leftist leanings. He’s the last of a fading breed of star, a reminder that even amidst the aesthetic and narrative revolution of the so-called “silver age,” the electric dynamism of Coppola and Scorsese and Penn and Malick, American golden boys were still making middlebrow films. Easy Rider made a lot of money in 1969, but Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid made far more.

In the ’70s, Ladies Home Journal called Redford a “nice, normal married sex symbol” — a striking contrast to the likes of Warren Beatty, who was busy getting in the pants of thousands of women. Redford was safe sex: always decent, never dangerous. You might say the same of Newman, but he always had a slight edge to his roles. He’s played the villain, the asshole, the drunk, and the memory of those performances inflects his face and our understanding of him with something Redford will always lack.

Redford still does it for me. But sometimes I wonder if he does it for the easiest part of myself.

Previously: The Many Faces of Barbara Stanwyck

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.