An Interview With Sheila Heti, Who Writes For Both Children And Adults

by Amy Fusselman

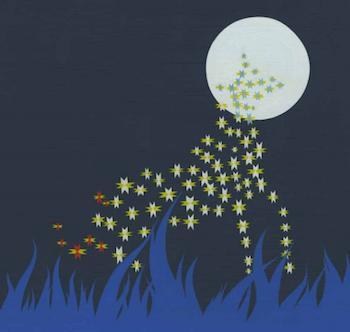

Happy Children’s Book Week, children. For those children who can read, we have below an interview with Sheila Heti, the author of We Need a Horse, an illustrated book for children featuring art by Clare Rojas. Heti is also the author of four other books, including How Should a Person Be?, which was nominated for The Women’s Prize for Fiction (formerly The Orange Prize) in March.

AF: I love how deeply you are playing in your work, and as you know, I am a huge fan of We Need a Horse. When I read it to my kids for the first time, my younger son said, “That’s the best book I’ve ever heard.”

That book is so thoroughly different from any other children’s book I have ever read. I wonder how that happened. Did you approach the project with the idea that you wanted to upend what you had encountered in other children’s books? Were there books that you took as models? And on another note, what books did you love as a child?

SH: I’m so happy to talk to you about this book. It was really strange — it was a commission, and I almost never write fiction on commission. But I wanted to do it and I went away to Montreal for a week and holed up in a friend’s house and wrote a lot of shit that I thought would work as a children’s story that was just awful — I sent some of these pieces to [Dave] Eggers and he was disappointed. So I came home — now nearing the deadline — and went out and bought all the books I loved as a child: Madeleine, Babar, The Monster at the End of this Book, some favorite Dr. Seuss Stories — and some new books I’d never seen before but loved. And I felt really depressed, because these books were so good, and I had no idea how they got so good. I particularly fell in love with / felt depressed over this book called Marshmallow. A lot of the new children’s books I looked at were really bad, though — moralistic or obvious or it was just clear that the writer was trying to make the kid act in a certain way in the future (less messy, more polite, more accepting). So I wanted my book to be more like Madeleine and Babar than these other ones.

I was days away from my deadline (or maybe I’d passed it) and an ex-girlfriend asked me to go to a party with her. I really didn’t want to because I was so stressed out about writing the story, but I went because I hadn’t seen her in a while, and we got a bit drunk and left the party and went to a bar and caught up. She is a brilliant, beautiful, kind person, and she was very depressed about not having a boyfriend and being single and childless and all this stuff, and I kept saying things to try to make her feel better, none of which was really working. Finally I had to go home, and she did too, and I just sat down and I wrote the story that became the story We Need a Horse. I was thinking of her as the horse, wondering why she had to be single and childless and “unloved” and I was trying to make her feel better with the story.

It was hard to do all those months I was trying because I kept trying to get into the mind of a 5-year-old and remember what it felt like to be five, and I was very far away from any understanding of what it was like to see the world from that age, but I think when I wrote the first draft of this story I felt like a little girl and I knew, for a few minutes, the world in the way I knew it then…

For a while after it was published I’d read it to myself before I went to sleep at night, and it made me feel really secure. I’d never actually ever written something before which was designed to comfort. I think what’s happening in the story is not just what I thought my friend needed to hear, but what some very vulnerable part of me also needs to hear.

That is so interesting to hear because I find the book so un-comforting and that is part of what I admire most about it. But I am guessing that our different responses can be attributed to your focusing on the main character and the stories she is telling herself and my focusing on the world s/he is operating in. The world presented in the book is not a comfortable or knowable place, and the main character never fully understands it until s/he dies. The only book I can think of that operates in a similar territory is Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Match Girl.

I am struck, though, at your saying you wrote the book under the influence of “real feelings” vs. “real thoughts.” Tell me more about that. How are thoughts or feelings real (or not)? And how do you view thoughts and feelings in relation to your writing work?

That’s interesting. I guess for me the horse is already dead at the beginning, and the world the horse is operating in is a kind of limbo, and he reaches the next level of deadness (beyond limbo) when he accepts the unknowability about things, at which point he “understands everything.” I like that you don’t find it comforting! We always have this illusion that people read our stuff the way we do, but it’s never the case. It’s a scary thought because then you end up revealing things you don’t know you’re revealing! I guess when people say it’s hard for them to write or publish, it’s because they’re really aware of that fact, but I (and probably you, and everyone who publishes) block that truth out pretty successfully most of the time.

I didn’t mean to denigrate thoughts, which are as important as feelings. But sometimes the best work comes from a place in oneself that operates deeper than conscious thought. For instance, I have a pet bunny and a pet cat, and some of the stories were about them. I thought, “My bunny and cat are really cute, I should write about them.” So that’s what I mean by a thought. Whereas the feeling I had when I was writing the story was really complicated, all about the sadness of being oneself and about how difficult life is and about our striving and what it all means. It was a complicated emotion. I think when you write in that state, you’re operating from a much more interesting and universal intelligence than when you think, “My bunny and cat would be really cute in a book.”

For me, because my books usually take five or six years to write, lots of thoughts go into them — years and years of thoughts. So if you apply years and years of thoughts to something, that winds up being as complicated as a complicated emotional state. I think that’s why I like working on something for a long time. As for feelings, I don’t know how to generate feelings in the reader — or maybe I don’t want to, it seems manipulative to me — so I try to write when I’m experiencing strong feelings, and hope that those states I’m experiencing can be transmitted to the reader, not even by what I’m saying, but by the energy of the sentences — I think sentences have a different tempo or mood, just in their cells, when you’re writing in different emotional states.

I am intrigued with what you are saying about sentences having energy. What would you say is the relationship of written words to energy? Are the words a recording of the energy? Do they summon the energy? Is it another model?

I always think they’re recording the energy. I don’t think you can dissect a sentence to find it, I think it’s just there among all the sentences, within them and between them. Don’t you think something very essential about the writer always comes through in whatever they write? Character, energy, whatever it is. Different people have different tempos. I don’t know how to put it exactly, I just think there’s a human in the sentences, and in the human there’s everything that is that human. You can’t put that stuff in there intentionally or keep it out intentionally. It’s just there, apparent, like the face of someone on the street. It’s why people love certain books the way they love certain people, and don’t love other books the way they don’t love other people. Because the human is in it.

Also, the words/energy issue makes me think of your performing background and how, as an actress, the quality of the energy you put into reciting your lines is everything. This brings me to your latest book, How Should a Person Be? Tell me about the play-ness of this book, which is structured in five acts. Were there qualities of live performance that you were trying to get at in your writing of it? If so what were they?

I think there were. I wanted the book to feel like it was happening sort of as the reader was reading it, rather than that it had all been laid out. And part of the way I was doing that was to keep myself surprised — to not know where I was going, and to change the book as I was changing. Looking back on myself — the person I was when I was writing it — it seems like a young person to me, and someone with a kind of utopic idea about what a book could be. I wanted to write the book in my head, while walking in the streets. I didn’t want to write it, but to sort of live inside it. So I created a character — the Sheila of the book — and I kind of began living and thinking as her. It was very much a performance, but one that was so close to my life that I don’t know where one stopped and the other began. I’m glad I’m not in that time anymore, but I’m a little sadder in some ways now because it’s a good buffer against the world, to be performing in it. It makes you a little less vulnerable, and you can always say it’s not “you” that’s experiencing whatever you’re experiencing, and you can always end the show.

Also, Sheila, your rant about Israel’s cock in this book is among my favorite passages ever written. A brief excerpt, for those unfamiliar:

I don’t know why all of you just sit in libraries when you could be fucked by Israel. I don’t know why all of you are reading books when you could be getting reamed by Israel, spat on, beaten up against the headboard — with every jab, your head battered into the headboard. Why are you all reading? I don’t understand this reading business when there is so much fucking to be done.

Cocks aside, do you see this book as being overtly feminist? Was writing a feminist work a goal?

I don’t think it was the goal, no. I think the book is feminist in the sense that it’s a woman speaking a woman’s point of view without shading it so that it will be more palatable to the male point of view (or the multiplicity of male points of view). But I wasn’t trying to say anything in particular about woman or feminism or sexual politics.

Still, I’m open to it being called a feminist work, and feminist books have been among the most important to me in my life. But I don’t know what is a feminist book. Is The Second Sex feminist, or misogynistic? It’s very much angry at women and disparaging of women in many ways, yet we call it feminist. I think feminism is very complicated, but the more complicated it is, the better.

Any plans to write another children’s book?

The last time I was in LA I was in a cab and I had an idea about the moon that I wanted to write about as a children’s book. The idea felt very strong to me right then, and I should have written it that night, but I didn’t, and I’m no longer sure what was so great about it. Perhaps one day I’ll remember and then I’ll write it.

Interview has been lightly edited. Excerpts from We Need a Horse used with permission.

Amy Fusselman is the author of The Pharmacist’s Mate and 8. She is the editor of the online journal Ohio Edit, and she also writes a column, “Family Practice,” for McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. Her forthcoming book, Savage Park, A Meditation About Play, Space, Objects and Death, Written Expressly for Americans who are Nervous, Distracted, and/or Afraid to Die, will be out in 2014.