Ranch Life

I started watching this small documentary about ranching in Montana (“Ridin’ For the Brand”), mostly because literally every single protagonist is a member of my friend’s extended family in Big Timber, also featured in Sweetgrass, one of the most beautiful films I’ve ever seen. There aren’t a lot of smaller ranchers left, and it’s a hard life. I mean, to say it’s a hard life is really to devalue it: it’s a nineteenth-century-level hard life (for an American.)

And there’s a great part in which the documentary crew heads to NYC to ask people about their impressions of being a rancher, or ranch life, or the beginnings of meat, etc., and at first I thought, “oh, come on, people aren’t this far removed from the process, right?” but then I remembered that I have actually heard people say:

That the job of the rooster on the farm is to be an alarm clock, like in the cartoons.

That if you were to take your dozen eggs out of the fridge and put them in an incubator, you’d have baby chicks.

Which, well, it’s not true! But, then, I get my meat every winter from these ranchers, and that’s not “real” either, by factory farming standards. When my rancher friends are raising a calf for me or themselves, they skip the hormone thingie in the ear. They’re grass-fed. Same with their lambs. You can go visit your lamb. They keep border collies to herd, and Great Pyrenees for guarding. Two years ago, a pack of wolves lured six of their Great Pyreness off their land, and killed them. Shearing just happened on the ranch, and there was a seven months pregnant woman hoisting her belly over a barbed-wire fence to help. It’s a seasonal life. They can very rarely come visit you; you have to go to them. And if you’re going to visit them, you’re going to work, because that’s what they’re doing. And then there’s pinochle and dinner and sleep.

Every year, a mother sheep will die, leaving a lamb, and a lamb will die, leaving a mother sheep. And when that happens, my friend has physically skinned the dead lamb and wrapped that skin around the orphaned lamb, just long enough that the mother sheep will accept it as her own. Once she had a sheep (or a “ranch maggot,” because no one who works with sheep develops much fondness for them) who was dumb even by sheep standards, and whenever it was time for lambing, she’d give birth in the creek, where the lamb would obviously drown. So for that whole month, they had to watch that sheep like a hawk so they could drag her out of the creek, wet and pissy.

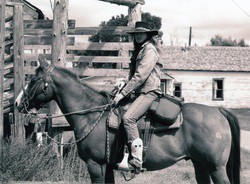

They’re harder on their horses, of course, than we are on ours. My horse is a luxury and a pet and a companion and a piece of sports equipment. My friend’s dad, Alvin, may love his horses, but they’re tools, first. When he does comes to visit and my horse is acting like a doofus (always), he says that if she was his, he’d put a pack on her and take her up into the mountains to hunt elk. If a horse likes to screw around, a few months of negotiating winding mountain paths with two elk on his back will generally convince him it’s time to grow up.

And when Alvin and Marilyn are ready to be done with the ranch, I don’t know what will happen to it. Their kids probably won’t want to ranch. There’s no money in it. It’s really hard. The land is worth a fortune, but who wants to buy it? Probably you could divide it up and sell it as individual hobby farms to people from the city. Sometimes Alvin makes some extra money helping to build houses for actors who decide to buy property in the area. And those houses don’t look anything like their own house, because their own house often has a sick animal sleeping by the stove, or they’re butchering on the kitchen table.

Texts From a Rancher:

“U want chops or steak or ground lamb or what?”

“U like those thin little deer steaks, right? The fajita-y ones?”

“Driving the lamb down to Utah alive and butchering there”

And, right, do not make the mistake of thinking these people are saints. They’re extremely conservative. They mistrust the government, which they think doesn’t understand their lives (they’re right about that). They’re harder on their kids than they are on the animals. But mostly, they’re hard on themselves, and they’re generous to you. And I’ve come to love Alvin and Marilyn, although we’re very different people. There are many different ways to live a good life. And I admire them, and I admire what they value in women: toughness, strength, kindness, goodness. It’ll be sad, I think, when there are no more small ranchers left. It’s not that far off.