The Mother of Dragons Looks Into Day School Options

Ian Misselthwaite drained his tea and allowed himself the rare privilege of kicking off his shoes and resting his sock-gartered feet on the desk. Enrollment was full, the endowment secure, the leak in the upstairs boys’ toilets finally defeated. The fall semester was scheduled to begin next Monday, and already a few parents had found his direct line in order to ring him about uniforms and dormitories and books and the thousand niggling problems that he, as headmaster, could hastily delegate to his secretary.

“Another fine year for the Dragon School,” Misselthwaite murmured to himself, pondering the wisdom of digging in his lower-right desk drawer for the flat bottle of brown liquid that was usually used only in times of great trial or great celebration.

“Mr. Misselthwaite, sir?” his secretary whispered urgently around the door. “There’s…there’s a parent here to see you.”

“Well, put them off,” he said.

“I tried. She’s…she’s rather insistent. And she’s naked, so I thought it best not to leave her wandering the halls.”

“Good Lord! Send her in.” Misselthwaite hastily stuffed his feet back into his shoes and swung them under his desk while straightening his tie.

The woman who entered immediately distinguished herself on several counts: she was, again, completely naked. She was disturbingly beautiful. She was breastfeeding two baby dragons, while a third immediately defecated on the hooked rug Misselthwaite’s wife had made for the hearth. She stared at him with some measure of skepticism, which he found curious, under the circumstances.

“What can I do for you, Mrs…”

“My name,” she said, “is Daenerys Targaryen. Or Daenerys Stormborn. I will also answer to Daenerys Drogo, or Khaleesi, but, for our purposes, perhaps ‘Mother of Dragons’ will suffice.”

“Ha ha ha,” Misselthwaite said. “Enrollment is quite full, it might be best not to get ahead of ourselves!”

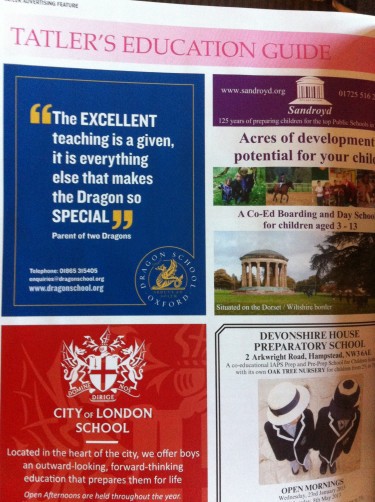

“Is this, or is this not, a school for dragons? I read Tatler’s education supplement, and it seemed quite clear on this point.”

“It is! It certainly is. One of our earliest dons was named ‘George,’ you see, so in honour of Saint George and the Dragon, we got into the habit of referring to the students as such. It’s just one of our little traditions. We also allow students to call masters by nicknames. They call me ‘Squidgy.’ Parents tend to find it charming.”

Misselthwaite paused briefly to draw breath, noting that one of the baby dragons had laid waste to his multi-volume set of “A Dance to the Music of Time,” and wondering if he could safely boot him away from the term reports. He chose not to.

“I’d like to hear about your curriculum. What percentage of classroom time is spent on dragon-specific information? Fire safety, flight, navigation over great distances, responsible hoarding, sustainable diet, etc.?”

“We feel strongly that a grounding in Latin and Greek is the cornerstone of any education,” Misselthwaite said. One of the baby dragons unlatched from his mother’s nipple, and Misselthwaite felt his eyes drawn helplessly to her chest. Could he ask her to cover up? He remembered that a local preparatory school had been forced to weather a three-week nurse-in after a recent incident, and decided against it.

“Perhaps you’d like to return with your husband?” he said.

“My sun and stars is dead,” she said, flatly. “I smothered him with a pillow, but the witch had already killed his heart. He was only a shell, where once he ravished me repeatedly and led the khalasar to great victories.”

“Oh, dear,” he said. “We do have excellent, excellent pastoral care available to our students. Would you like to meet with the chaplain?” He grabbed for the telephone.

“That will be unnecessary,” she said. “I no longer believe in the wisdom of necromancy, but only in the cleansing power of fire.”

“I see,” he said. “Are you interested in our day program? Most of our students are boarders, but as many of our parents are local…”

“Yes,” she said. “They are still weak, and need my milk. I assume you have plenty of blood-soaked bread?”

“Hm,” he said. “Fridays we have Welsh rarebit.”

“Rabbit? That will do nicely.”

Misselthwaite elected against correcting her.

“If you’re interested in learning the rate at which our graduates matriculate at Oxford and Cambridge, I have several pamphlets in the halll…”

“My children,” she said, “have but one goal: to win me back the iron throne, and decimate our enemies.”

“Ah,” he said. “Well, you know, so often they surprise us, don’t they.”

“Yes,” she said. “Everyone thought their eggs were inert, merely decorative. It was not until I brought them into the flames with me and perched upon my husband’s burning corpse that we realized their power.”

“Quite. Shall we turn to the fee schedule?”

“I have my checkbook outside, with my silver mare.”

“Excellent,” he said with relief, for his quota of scholarship recipients had already been filled for the year.

They shook hands, and Daenerys swept from the office, her children circling her and mewling.

“At least,” Misselthwaite mused to himself while downing the bottle at one go, “we’ll have greater diversity in next year’s brochure.”