Scientology and Me: Part One, Growing Up in the Church

by Stella Forstner

I was about the age Suri Cruise is now when I had my first session. Mickey, my first-grade teacher at the non-traditional school I attended, had announced that day that he would soon be leaving for a new job somewhere in California. All I remember now of Mickey is his warmth, and his soft, crinkly eyes and thick black beard, but the day he made his announcement, I was devastated in the way only a six-year-old can be — someone I loved was leaving me! The world had turned cruel. I trudged home to my mother, sobbing, and though I’m not sure who brought up the idea first, I knew a session was just what I needed.

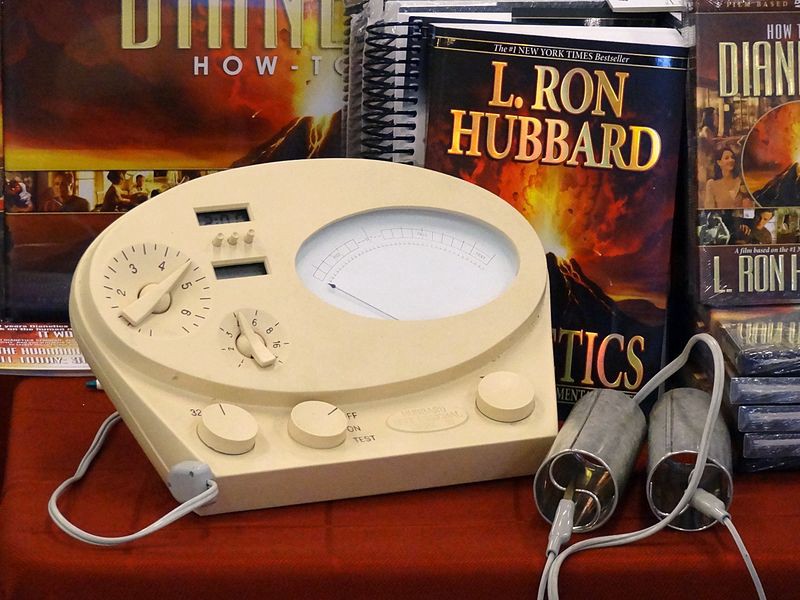

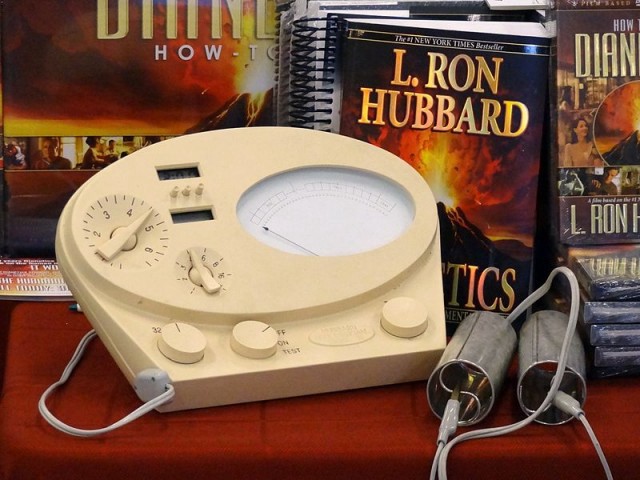

Because my brother was an infant at the time, my mother wasn’t going into the mission regularly, and when she did auditing it was from home. I remember the E-meter set up on a table in the light-filled kitchen, the screen facing her. I sat across, gripping metal cans narrower than soda cans but still too big for child-sized hands. I felt excited, a little nervous, my sadness about Mickey already dulled by my entry into the adult world of the church and the confidence that I could make these painful feelings of loss go away.

The E-meter, short for electropsychometer, operates on the same principle as a lie detector, measuring electrical fluctuations from your skin believed by Scientologists to correspond to interior states and unconscious feelings. A high-level Dianetics (the ‘science’ upon which the practice of Scientology is based) auditor, my mother’s job was to guide her clients through whatever issues they were dealing with, using the E-meter as a tool to locate sources of mental turmoil they were not themselves conscious of. According to Dianetics, uncovering these sources — mental images known as engrams — rids them of ‘charge,’ which is seen both physiologically as it registers in the movement of the needle on the screen of the E-meter, and mentally as it binds an individual to illness, mental anguish, and unconscious impulses.

I was fascinated by the E-meter when I was little; wouldn’t you be? The machine promised to show you what was going on inside the black box of your brain and give you the power to change it. I sometimes turned the machine on and played with it secretly, but I knew from my mother that I couldn’t audit myself until I was older and trained to do so. It seemed like a kind of magic the way my mother was able to read my feelings through the E-meter, though to be fair my tear-stained six-year-old face probably made things pretty transparent. She identified the source of my upset (I was afraid I would never see Mickey again and that he would forget me), helped me to devise a solution (I could write to Mickey and perhaps someday we could visit him in California), and left me exultant as she ended the session with the words “your needle is floating.” I felt happy and in control.

A ‘floating needle’ meant, I knew, that all had been resolved. I knew this because my mother was an auditor and she made people happy, helped them to explore and eventually triumph over their problems. I remember a client showing up at the house with a bouquet of flowers for my mother, intense gratitude on his face. He credited her and the auditing she had given him with helping him to change his life. I didn’t see my mother’s clients often; she usually worked long hours at the mission, an independent Scientology franchise by that time subservient to the ‘orgs’ (short for organization) operated directly by an arm of the church.

My mother did most of her auditing at the mission, a place I remember as overwhelmingly brown, in that woody style of the late ‘70s/early ’80s. I hung out there often, mostly because she couldn’t afford daycare, spending hours in the basement playing with the clay demos used in courses and trying out my atrocious jokes on the stressed-out staff. The atmosphere was so casual that I was sometimes allowed to take part in Dianetics training called the communications course — a set of techniques intended to help people become more comfortable in social situations. Part of what were called the TRs (short for training routines) for this course involved a drill called ‘bullbait;’ the student had to remain calm and focused while their partner, typically another student on the course, did whatever they could to make them laugh or otherwise break. My stretched-mouth-pig-nose-exposed-under-eyeballs-face took down many an otherwise excellent bullbaitee.

I loved being allowed in the adult world of the church, not only because I was a child who adored adult company but also because I, like the adults, was taken in by the feeling that I was part of something big and important. I remember when a new promotional film was released and the city org set up a viewing at a local movie theater. In the opening scene the earth was shown rotating on its axis, a great shadow spreading over it as the narrator proclaimed the rapid and unstoppable growth of Scientology. We had the power to make people better, stronger, to release them from negative emotions; I had seen evidence of this and even experienced it myself. I felt special and proud.

But the Church wasn’t always a good place to be a child. For a time I had attended a Scientology kindergarten where discipline involved long stretches of time in the corner reflecting on one’s misdeeds. After I came home crying from school on half a dozen occasions, my furious mother pulled me out of the school and found a way for me to start first grade early in Mickey’s class. Though an excellent auditor, my mother was not always the best Scientologist; she believed in and practiced church principles but was too stubbornly independent to swallow everything whole. When my mother used Scientology techniques (or ‘tech’ as we called it) on me, she did so gently, believing that reincarnated thetan (thetan being roughly equivalent to spirit or soul) or not, I was still a child. I was raised on the principles of Dianetics, but not the ones that you’ve probably heard about, because the parts of Scientology that are useful for things like dealing with personal relationships or teaching children about responsibility are too pragmatic and boring to attract the kind of attention that space aliens do. When I did something wrong — stole a cookie, failed to do a chore, tormented my little brother — I first had to be honest about it, avoiding an ‘overt’ that could perpetuate my bad behavior, identify the wrong I had done and who I had wronged, and finally devise suitable ‘amends’ so I could make things right.

I had arrived on the scene during the very end of my parents’ relationship, and since I only saw him on summer visits to the Midwest it took years for my father to figure out how to relate to me, let alone how to raise me (his default of mini golf, ice cream, and Six Flags season passes wasn’t bad, though). Scientology provided him with a road map for interaction, and though it was not always the right one, I think it was important to him to have guidance. As I seemed to always be scraping my knees or bonking myself in the head (too much mini golf and ice cream, perhaps) my father would frequently treat me with Scientology’s healing practice, a ‘touch assist,’ a technique employed by Scientology’s volunteer ministers (following emergencies from Ground Zero to the Haitian earthquake). An assist is a simple procedure that involves diverting attention from the source of pain or grief while providing a dose of basic human compassion. His voice even and soothing, my father would ask questions intended to orient me in my body. Where does it hurt? My knee. Can you touch your knee? Yes [touches knee]. Does your ear hurt? No. Where is your ear? [Points at ear.] Can you touch your ear? And on it would go, usually until I demanded an end. After I was seven or eight, I found the process a little ridiculous and sometimes wished for a simpler comfort, but I had to admit it helped.

My parents met in the church in the early 1970s and married young. In their wedding pictures, my mother is 19 with pale blond flat-ironed hair, thick eyeliner and pale lips, and a white velvet dress with bell sleeves trimmed in lace, my father just a few years older with muttonchops and a ruffled black dress shirt under his white tuxedo. Like the people who had decorated the house where I grew up in garish yellows and oranges and installed an avocado fridge, the people in these pictures seem confident these fads would endure. Certainly at the time Scientology seemed little different from many of the other faddish groups, movements, and subcultures that had sprung up following the uproar and instability of the 1960s. Like EST, TM, yoga, Up With People, or building your own geodesic dome, Scientology promised a new way to both transform yourself and create a better world. At the mission there were always copies of a popular booklet called “The Way to Happiness” lying around, and I remember being certain it would be the first course I would take when I was old enough; the cover featured a rainbow bursting above a grassy path. My Little Pony would have been at home there.

I don’t remember thinking of myself as different from other kids, but then there was nothing visibly Scientologist about me — nothing I had to do or couldn’t do because of my parents’ religion. Like most children, I was well attuned to strangeness among my peers and not particularly sensitive about showing my curiosity or judgment: a neighbor had some Mormon friends, and I was baffled as to why they weren’t allowed to drink soda — never in their whole lives? And what could soda have to do with a religion anyway? I may have thought of Scientology like others see their own religious practices, but I never thought of it as a religion: if I could have phrased it as such I would have described it as something like a scientific philosophy. And so I was stunned, if a bit excited, the first time I saw Airplane on television and caught a mention of Scientology in a clearly unflattering context:

If I had grown up in the church 20 or even 10 years later than I did, I’m sure I would have become inured to things like this, accustomed to all sort of passing insults to the church and to its members, and I’m sure I would have grown more defensive with outsiders, protecting myself and my family from embarrassment or attack by hiding our association with the church. Back then Scientology had few celebrities on its rosters and attracted little media attention, in large part because of its aggressive and litigious attacks on its detractors. The absence of the internet meant that I heard little outside criticism of Scientology; it also meant that when my mother started to grow disillusioned with the church she had nowhere to go to confirm her suspicions about the organization or to find a way out. But I don’t doubt that children growing up in the church today feel any less than I did that they are a part of something important, that there is a kind of magic around the name L. Ron Hubbard. I’m sure they, like me, peep curiously into “Ron’s Office” — the roped-off room in every org filled with models of his ships, copies of his books, even a glass ashtray on his heavy wooden desk.

I remember how strange the darkened org looked in the flicker of candlelight on the night L. Ron Hubbard died, how excited I was to be entrusted with my own candle next to my mother and stepfather in all that awkward silence. I felt I had been lucky to have been alive while he had been alive, even though I’d never seen him in person, and imagined telling future generations about my attendance that night. Instead it became an anecdote to wield at parties, a way to mute the complexity of my family’s long entanglements with the church.

NEXT: What Scientologists actually believe.

Stella Forstner is a pseudonym for a Hairpin devotee who wishes to protect her family’s anonymity.