Scandals of Classic Hollywood: The Exquisite Garbo

by Anne Helen Petersen

Greta Garbo did not inhabit this earth. She flitted about in the celluloid heavens, showing her face and, later, offering her voice at sporadic intervals. Her skin was flawless, the arch of her eyebrow was perfection. She was never a child, she never aged. She didn’t cry, and laughed so rarely that when it happened onscreen, the studio focused entire publicity campaigns around it.

She was never Greta; she was always Garbo. And she must be seen — projected, larger-than-life, on the big screen — to be believed.

Garbo is one of the remaining enigmas of Hollywood history: did she love men? Women? Both? Did she turn her back on Hollywood? Did she truly “want to be alone”? Was she a figment of Hollywood’s imagination, the product of light and mirrors, or a woman in control of her own destiny? To me, she is pure cinema: the most exquisite alchemy of light, celluloid, and the human form.

I mean, Roland Barthes had it completely right:

Garbo belongs to that moment in cinema when capturing the human face still plunged audiences into the deepest ecstasy, when one literally lost oneself in a human image as one would in a philtre, when the face represented a kind of absolute state of the flesh, which could be neither reached nor renounced. A few years earlier the face of Valentino was causing suicides; that of Garbo still partakes of the same rule of Courtly Love, where the flesh gives rise to mystical feelings of perdition.

Neither reached nor renounced! Mystical feelings of PERDITION! (I am so with you, Barthes — can I come hang out with you and your mom in your French apartment and talk about wrestling?)

When Barthes says that Garbo’s face makes you feel mystical feelings of perdition, what he’s really saying is that there was something so perfect, so transcendent, about Garbo’s face and demeanor — you could lose yourself in it. A close-up on her face was tantamount to a close-up on your own: it was so intimate that her feelings (despair, resignation, bliss) became yours.

It’s tempting to talk about Garbo purely in theoretical terms. As Barthes points out, she wasn’t a person so much as an idea — an ineffable idea that buttressed early cinema and its power to millions of audience members. But Garbo was, of course, once a child. She did age, she did wilt, she did turn her back on Hollywood — a decision that only amplified her mythic quality. I’ll do my best to explain how, and why.

Garbo grew up in Stolkholm, Sweden, in the dawn on the 20th century. Her parents were working-class, and biographers frame her as a sullen, removed girl who loved to play alone — characteristics that may have been true, but they were doubtlessly accentuated to fit with what would later become Garbo’s overarching image.

She finished school at 13 and, as was common practice at the time, went to work: first at a soap factory, then at a department store, where she eventually started modeling hats for the store’s catalog, which she in turn parlayed into a full-time modeling gig. Photos turned into commercials, commercials turned into film shorts.

She spent two years in acting school before a super well-known Swedish director cast her opposite a super well-known Swedish star in an adaptation of Gosta Berling’s Saga, one of the most important Swedish books of the (then) last 30 years. I mean, no pressure, Garbo, you’re just going straight from the minor leagues to the World Series.

“1923 — age 18 (by Olaf Ekstrand)”

The super well-known director, Mauritz Stiller, knew Garbo had something, and he helped cultivate it, teaching her how to respond and shape herself to the camera. The demands upon the actor were entirely different than they are today: in black and white, without sound, the eyes and face had to tell what even the best subtitles could not.

Stiller took over managing Garbo’s career, bringing her to Turkey to make a film and, when funds ran out, arranging for her to star in a German picture, Joyless Streets. Soon thereafter, MGM’s Louis B. Mayer made a scouting trip to Berlin.

Historians and fans fight over how Mayer decided he wanted Garbo. Some people say he thought he wanted Stiller, and agreed to screen Gosta Berling, and then decided he could make a star out of Garbo. Others say he had seen Gosta before coming to Berlin and had but one objective: GET THE GARBO. Even if Stiller insisted on coming along — fine. But “the girl” was number one.

It doesn’t matter what actually happened — those who want to believe that Stiller was the commodity (and responsible for Garbo) will; those who want to believe that it was always all-Garbo, all-the-time, will believe that. Aprochrophyl history is great at conforming to our ideological needs; just ask the Bush family.

Mayer signed Garbo and Stiller to MGM contracts. No matter that Garbo spoke no English: it’s all in the eyes! Both Garbo and Stiller assumed they’d be working together in Hollywood, but unlike the relationship between Marlene Dietrich and von Sternberg — whom Paramount hired five years later in an explicit bid to create their own “exotic” European star — Stiller never served as her (final) director. For Garbo’s first Hollywood film, she made a splash playing a vamp in The Torrent (1926). MGM then paired her with Stiller for a similar role in The Temptress, but Garbo’s sister died early in production, MGM refused to let her return to the funeral, and Stiller was unpracticed in the ways of American production. Garbo was miserable; Stiller was replaced; reshoots began. The film was a smash, and Garbo, already embittered by Hollywood, was a star.

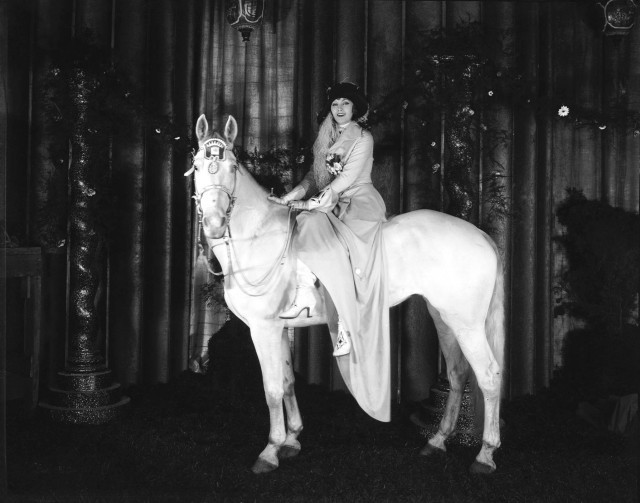

And I mean how could she NOT be, sitting on a horse like this:

A slew of films followed, most of them variations on the same theme. These pictures are good, fine, great, but they show how MGM hadn’t yet figured out Garbo’s true draw, onscreen and in publicity photos: the close-up. Cinematographer William Daniels figured this out on Flesh and the Devil — a film that almost didn’t happen.

After The Temptress wrapped, Garbo was understandably pissed. They didn’t let her go home for her sister’s funeral, they fired her mentor, and now they wanted her to hop right into another film, playing yet another vampy temptress. She’s still learning English. JEEZ.

But MGM sends a “sternly worded” letter, making it clear that she will film The Flesh and the Devil, and she will do it now. Flesh and the Devil is standard late-’20s silent film — women is sexy; woman tempts men; woman dies for her sins — but watch Garbo and co-star John Gilbert closely: it’s something you see in To Have and Have Not with Bogart and Bacall, in Mr. and Mrs. Smith with The Brange, even in Step Up with C-Tates and Jenny Dewan. They’re falling in love in front of us, and the chemistry is palpable.

Combine that energy with Daniels’ work with the close-up, and there it is: the film when Garbo became Garbo.

That look! It’s equal parts disinterested and orgasmic. The only person who does anything close today is Kristen Stewart. Stop your yelling and trust me.

Between 1927 and 1930, Garbo appeared in seven films — including two more (Love, A Woman of Affairs) with Gilbert, with whom she co-habited, on and off, the way we all did when we were 22 and a giant Hollywood star. The fan magazines went crazy and MGM did their best to exploit the romance as much as possible: the advertisements for their second film together promised “Garbo and Gilbert in Love.”

Garbo, in Love, yet clearly not impressed with MGM’s wordplay.

Hollywood was petrified by the idea of sound. They thought it was going to change/wreck everything, the same way that Hollywood thought color, television, digital, and 3D would change/wreck everything. Of course, in some ways they were right — “talkie” cinema is an entirely different artistic mode, with different codes of performance, than silent cinema. What’s more, sound technology was not only expensive and unwieldy (Singin’ in the Rain is a good starting point for understanding the struggles, but it’s also rather exaggerated), but each studio risked losing their entire stable of stars — unless they could prove that they could talk. Convincingly. Without working-class accents.

Garbo didn’t have a working-class accent, per se — she just had a heavy Swedish accent, which, in early 20th century America, was basically the same thing as a working-class accent. (Now, Swedish accent = fashion-forward guy you want to date RIGHT NOW.)

Truthfully, the underlying problem was never accents. It was distribution. When movies were silent, you could ship them overseas and simply translate the intertitles. Gestures need no translation. As a result, the film business was truly international — and Garbo had a tremendous European fanbase. In the early days of talkies, studios (American and international) tried to avoid dubbing by making two versions of a film: one in English, the other in the language spoken by the secondary market. Anna Christie, like Dietrich’s The Blue Angel, had two versions: one English, one German.

MGM thus delayed putting Garbo in a sound film for as long as possible. When they finally made the switch, they did it up big: promotional materials for Anna Christie promised GARBO TALKS!

Garbo doesn’t care if you like her voice or not.

And oh what a voice it is. Her first line: “Gif me a vhisky, ginger ale on the side, and don’t be stingy baby!”

That is Hairpinner if I ever heard one.

Garbo’s voice didn’t ruin her. It completed her.

Which was why Anna Christie was a smash: it was the top grossing film of the year and earned Garbo her first Oscar nomination. I mean, look at her face after an ill-advised shot:

[Close approximation of my face the first time I took a shot of Scotch.]

And the hits just kept coming: as a fallen woman in Romance (another Oscar nomination), an artist’s model with a sordid past in Inspiration, a circus dancer/mistress/fallen woman in Susan Lenox (Her Rise and Fall). If you’re sensing a theme, it wasn’t just to Garbo’s pictures: this genre of “Pre-Code” Film, as they were called, was enormously popular, featuring everyone from Garbo to Joan Crawford. Audiences loved an independent mistress lady, only they had to call her “fallen” which is clearly code for “sexually-empowered” or “resistant to patriarchy.” And Garbo released such an “erotic charge” in these films that MGM got all embarrassed and added a “moral” (read: something bad/reformative happens to sexual lady) ending.

The rough life of the fallen woman.

And then, there were the smashes: the titular character in Mata Hari (1932), based on the life of a woman with the best job hyphenate I can possibly imagine: exotic dancer-spy-courtesan. The proto-leggings, the earrings, the headdress, the 50 pounds of precious stone: this is MGM glamour at its finest.

(I love to think of how garish this outfit would’ve looked in color — like straight-up Bedazzled Mall — and how exquisite it looks in black and white.)

Later that year, there was Grand Hotel — the filmic version of the super-group, the all-star game, and the antecedent to Ocean’s 11, Love Actually, and Valentine’s Day, when you pack as many stars into a movie as humanly possible, hinge the plot to a single day/space, and hope for the best. Now, I could write a full-length paper on the atrocities of Valentine’s Day/New Year’s Eve, which take the idea of the all-star cast and strip it of the spirit. Seriously, those movies are for suckers. But Grand Hotel, it’s lovely: Garbo, Joanie Crawford, Wallace Barry, plus Lionel AND John Barrymore, all delicately orbiting one another. Think (far) less What To Expect When You’re Expecting; (far) more Gosford Park.

Garbo-mania ensued. Grand Hotel won Best Picture, and suddenly Garbo was earning upward of a quarter-million per film — then a preposterous amount. She used her value to renegotiate her MGM contract, stipulating more control over scripts and co-stars . . . which meant she could request former/current/who-knows lover John Gilbert as her co-star in Queen Christina.

Now, according to Hollywood history lore, “people” had heard Gilbert’s voice and decided that it sucked. If you’ve seen Queen Christina, you can understand how mystifying this conclusion is: dude has a normal, albeit slightly affected, Hollywood-actor voice. As film historians have pointed out, the true story was that Gilbert had an extravagant, $250,000-a-picture contract with MGM, and the studio wanted him out. More important, Louis B. Meyer loathed him (rumors of punch-outs abound). Meyer, MGM, or other powers that be thus ensured that he receive shit material — including the early-talkie His Glorious Night, in which Gilbert’s lines amounted to “I love you, I love you” repeated dozens of times over. (If that sounds familiar, it’s parodied in Singin’ in the Rain.)

Gilbert looked ridiculous, and his descent began — as did the lore of his “victimhood” to the transition of sound. By 1933, he had finished out his contract with MGM, and his career seemed to be over, yet he returned to the studio, on Garbo’s insistence, for Queen Christina. I kinda feel bad for him, and wish he was more notable in Christina, but this film is a true Garbo tour de force. I have eyes only for her.

For me, it’s a different, liberated mode of Garbo. Her Queen Christina is frustrated with gender strictures — she loves to wear pants, but she also loves a man; she must lead her country, but cannot do so encumbered by love. One moment she’s tromping around the castle, giving full-on kisses to ladies in waiting, the next she’s rolling around on furs in front of the fire, sharing grapes with John Gilbert:

It’s a famous scene, in part because so many have read Garbo’s own life into it. As she walks around the room, caressing and embracing various objects, memorizing the room and experience that she must soon forsake, it’s as if Garbo herself is saying farewell to the life she would have had, had she not become the most famous face on the planet.

Plus the scene at the end, when the camera holds on her face forever and it seems as if her heart and will is hardening before your eyes. According to cinematic lore, director Rouben Mamoulian told Garbo to think of nothing, nothing at all, allowing each audience member to write their own ending onto her visage.

Queen Christina is also famous — along with Dietrich’s various early top-hatted turns — for blatantly encouraging blissfully queer readings. There’s the matter of the kiss, of course, but then there’s also Garbo herself: the pants, the generalized androgyny, the declaration that she’ll “die a bachelor” — it’s all too, too good. As film historian Alexander Walker points out, she walked like a man: “Garbo has a great length of leg between kneecap and pelvis, and it gives her movements a poston-like quality, a steely directness … she cannot take six steps without making it look like the start of a hike.”

Even if the lady did walk like a man, she still posed like this:

There were also myriad rumors of Garbo’s lady-dalliances: with Dietrich, of course, but also with Louise Brooks, Josephine Baker, writer Mercedes de Acosta, stage actress Eva Le Gallienne, and director Dorothy Arzner, all of whom allegedly met for regular “sewing circles,” if you’re picking up what I’m putting down.

As with Cary Grant, I’m less interested in arguing about whether Garbo was, in fact, queer — although it seems clear that she totally was (letter to her “close friend” Mimi Pollack: “We cannot help our nature, as God has created it. But I have always thought you and I belonged together.” Plus, naked hiking with Dietrich in Germany?!?) — and more interested in how her image made such readings possible and plausible. If queer viewers with no filmic representation of their lifestyles decided to read queerness into Garbo’s heterosexual performances, awesome. I’m never against audience members negotiating their own pleasure, especially since the contemporary American film industry continues to pride itself on providing pleasure only to white, middle-class, 18-year-old heterosexual boys.

[Pause for unceremonious link to topless Garbo in khakis and inexplicable jewelry.]

The films became sparser: playing Naomi Watts’ part in the first version of The Painted Veil (1934), the only Anna Karenina we ever needed (1935) (okay, okay I actually am excited for the upcoming Keira Knightley version. Two words: hot moustaches), and just exquisite and all sorts of tragic in Camille (1936), a performance for which she earned her third Best Actress nomination.

I must admit, sausage curls are not Garbo’s best look.

But Conquest underperformed, and Garbo, along with Joan Crawford, Katharine Hepburn, and Mae West, were deemed “Box Office Poison” — which is kind of like calling Will Smith a huge, pitiful failure after Seven Pounds. Still, her turn in Lubitsh’s Ninotchka was hailed as a “come-back” — and lured viewers with the promise that “Garbo Laughs!” This movie slays me, in part because it so cannily plays on Garbo’s established image as a serious-face who dies at the end of two-thirds of her films. It’s clear, too, that Garbo’s in on the joke, reveling in her own lampooning.

The film was a smash, despite the fact that it was banned in Russia for its depiction of life under Stalin as hilariously dour. She took two years off, perhaps saw that the war was cutting off her European audience (which fueled much of her sustained popularity) and deemed her final performance in Two-Faced Woman (1941) “my grave.”

I hope my grave looks something like this.

And then — nothing.

An unceremonious retreat; a private, rarely-seen existence in Manhattan. Here and there, rumors of a woman in large glasses disappearing around a corner, coupled with whispers of a return and offers to play Sarah Bernhardt, George Sand, Dorian Gray, the Duchesse de Langeais for the top directors in Hollywood.

Unlike other stars of her era, Garbo didn’t fade. She simply disappeared. Or, more precisely, disappeared from popular life, and lived out the rest of her private life in relative solitude. She had friends, she went on walks, she had the same housekeeper for decades. But she never married, never appeared on (god forbid) television. People always thought she ran from Hollywood, murmuring “I vant to be alone,” her famous phrase from Grand Hotel. The reality, however, is most likely far less dramatic. Various people have claimed she was depressed, perhaps bipolar, certainly chronically unhappy.

Maybe so, maybe not. Such readings align with Garbo’s picture personality, with its throughline of despair. Garbo as a plump, contented grandmother simply would not compute. But as always, we can’t know what happened to the actual body and mind behind the face. We only know what became of her image: its mythic quality increased exponentially.

Other stars of the silent era aged before us, prostrating themselves to the gods of television and B-movies. But Garbo’s image remains frozen in amber, a testament to the preservational power of absence. But it was more than the lack. It was the mystery, the belief that she ended as one of her tragic heroines. It was pleasing — the same way Paul Newman’s gradual, philanthropic, blue-eyed fadeaway was pleasing, or Cary Grant’s final marriage to a woman decades his junior was pleasing. It seemed to fit. It made sense. It ratified the unspoken hope that our stars are who we think they are — the same hope that manifests as outrage when stars’ actions prove discordant with their own myths.

Garbo had an undeniable gravity. She pulled the viewer into her orbit, and suddenly she was the entire universe. It was and is unsettling, and I think that’s the source of Barthes’ mystical feelings of perdition. I could look at pictures of her all day and still want more: she’s either the most beautiful person in the world or the oddest. Her face, as Barthes understood, was a capital-I idea. And like all of the best Ideas, it challenges while it seduces, grows better and more complexly intriguing with age.

Just look at this Idea. And see if you can look away.

Previously: The Long Suicide of Montgomery Clift.

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.