The Search for Decolonial Love

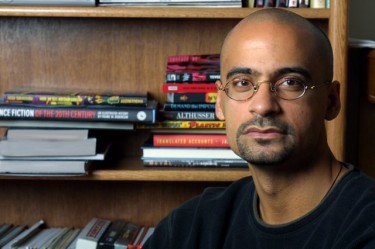

Boston Review has parts one and two of their interview with Junot Díaz online. Honestly, we want to just drop massive chunks of unaltered text on you, so let’s just do one and then you can read the rest yourselves, okay?

Much of the early genesis of my work arose from the 80s and specifically from the weird gender wars that flared up in that era between writers of color. I know you remember them: the very public fulminations of Stanley Crouch versus Toni Morrison, Ishmael Reed versus Alice Walker, Frank Chin versus Maxine Hong Kingston. Talk about passé — my students know nothing about these exchanges, but for those of us present at the time they were both dismaying and formative. This was part of a whole backlash against the growing success and importance of women-of-color writers — but from men of color. Qué irony. The brothers criticizing the sisters for being inauthentic, for being anti-male, for airing the community’s dirty laundry, all from a dreary nationalist point of view. Every time I heard these Chin-Reed-Crouch attacks, even I as a male would feel the weight of oppression on me, on my physical body, increased. And for me, what was fascinating was that the maps these women were creating in their fictions — the social, critical, cognitive maps, these matrixes that they were plotting — were far more dangerous to the structures that had me pinioned than any of the criticisms that men of color were throwing down. What began to be clear to me as I read these women of color — Leslie Marmon Silko, Sandra Cisneros, Anjana Appachana, and throw in Octavia Butler and the great [Cherríe] Moraga of course — was that what these sisters were doing in their art was powerfully important for the community, for subaltern folks, for women writers of color, for male writers of color, for me. They were heeding [Audre] Lorde’s exhortation by forging the tools that could actually take down master’s house. To read these sisters in the 80s as a young college student was not only intoxicating, it was soul-changing. It was metanoia.

Right? What is “metanoia,” and how can we work it into more conversations?