Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Warren Beatty Thinks This Song Is About Him

by Anne Helen Petersen

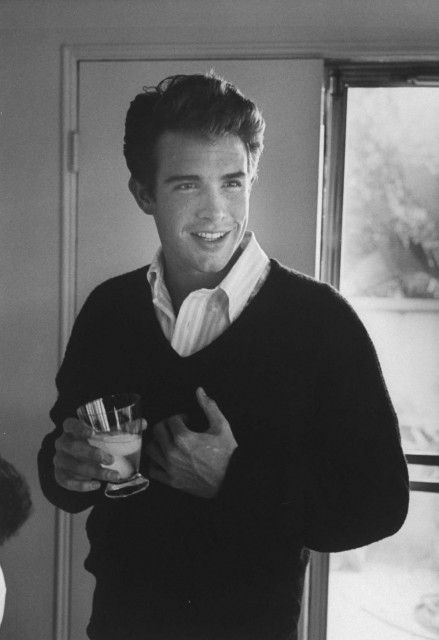

Warren Beatty wasn’t your typical handsome. There was something earnest about him — something plaintive, needy — that made women want to protect him. And, of course, sleep with him. And if you know anything about Warren Beatty, it’s probably that he’s rumored to have slept with 13,000 women over the last 75 years. I call bullshit on that math, but womanizing has nevertheless become Beatty’s defining characteristic. His sister famously said he “couldn’t even commit to dinner.” Woody Allen once asked to be reincarnated as his fingertips.

But here’s the thing: for all his flirtatiousness, for all his storied ability to romance over the phone, for all his “What’s Up Pussycat”-ing, Beatty was also one of the most important figures in film over the last 50 years. He was demanding, he was irritating, he wasn’t always a good actor, but he might have been brilliant. And that — along with the prodigious womanizing — is what I’m going to remember him for today.

I’m talking about Beatty in the past tense, but he’s very much alive — in fact, he’s the first subject of this series who’s still alive, despite beginning his career at just about the same time as Paul Newman and Natalie Wood. But he hasn’t made a film since 2001 (let’s not talk about it) and seems rather retired. He, along with Shirley MacLaine (his sister), Jane Fonda, and a handful of other stars, still signify the “Silver Age” of Hollywood, when the studios, caught in freefall, allowed a handful of experimental, untested directors with names like Coppola, Scorsese, and Polanski to make inexpensive yet exquisite masterpieces.

The story of Beatty’s career is the story of the last 50 years of Hollywood: his first work was in television, he moved to films made in the last gasp of the studio era, and finally found success by putting together film packages (story, script, producer, director, and stars — of some iteration thereof — included) and selling them to the studios. He grew up in Virginia, the son of educators and baby brother to Shirley, enjoying things that kids of teachers generally do: reading and playing the piano. But something changes when he reaches high school — he’s elected class president, plays football like a pro, and is, essentially, big man on campus. He’s known as “Mad Dog.” Despite offers from several schools to play football, he goes to Northwestern to study drama. How very Finn Hudson of you, Warren.

But drama school doesn’t stick, and after a year, Beatty moves to New York City, where his sister is acting on Broadway. He takes some acting classes with Stella Adler, a.k.a. the American promulgator of The Method. To make rent, he works all sorts of standard starving-actor jobs: bricklayer, dishwasher, and, my personal favorite, cocktail lounge piano player.

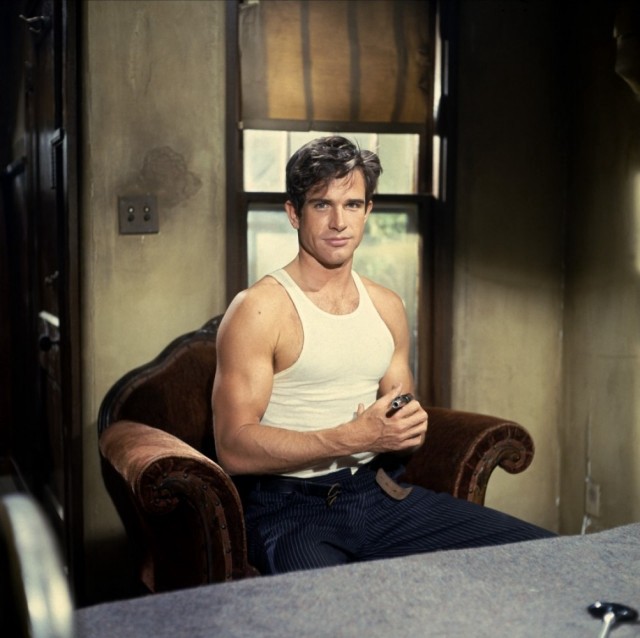

So picture this: Beatty. In New York. In the 1950s. Kids trained in the Method are blowing up all over the place — Brando in Streetcar, Clift in A Place in the Sun, James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, Paul Newman in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Beatty clearly saw what his life — and talent — could look like. But he couldn’t seem to land the right auditions, and spent time languishing in bit parts on various “anthology” television series, the ’50s version of Masterpiece Theater meets network television.

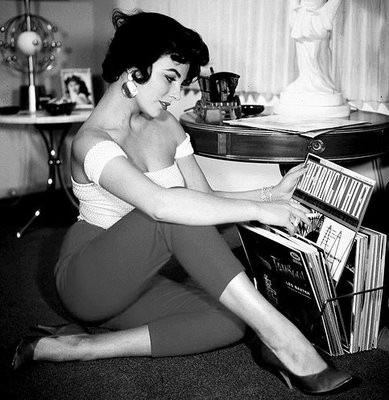

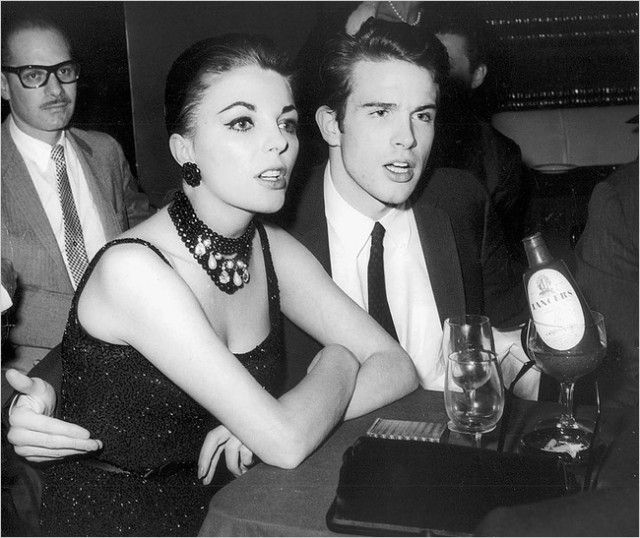

During this period, he also hooked up with Joan Collins. Now, if your memory of Joan Collins is anything like mine — which is to say filled with shoulder pads and ’80s power suits — then you need to replace that memory with this one:

Girl was a minx. A minx with a contract with 20th Century Fox, which wanted to pit her against Elizabeth Taylor. Collins was getting roles, Beatty was not, but they were head-over-heels for each other — and apparently having a tremendous amount of sex. They became engaged in late 1958, moving to a teensy apartment in the Chateau Marmont.

Beatty may have been a romantic, but he also understood the benefits of a demi-star as a fiancee. He finagled a part in playwright William Inge’s A Loss of Roses. Inge was gay and apparently had a thing for Beatty; Beatty, already resourceful, played that thing into an audition for director Elia Kazan’s latest production, for which Inge had written the script.

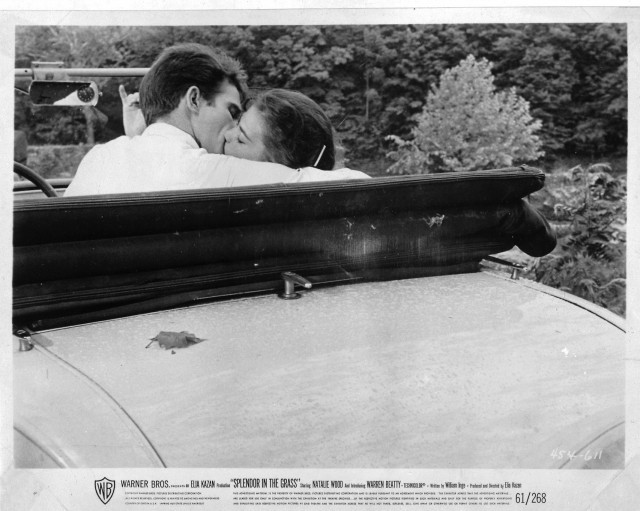

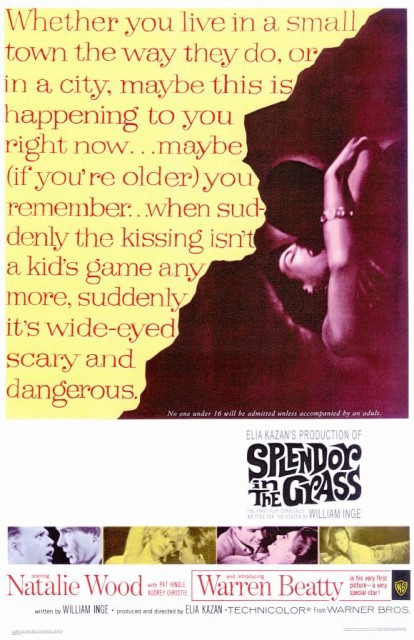

That production was a little something called Splendor in the Grass. Beatty won the part of Bud Stamper, a small-town middle-American teen with, well, urges for his girlfriend, played by Natalie Wood in her comeback role. (I love it when 23-year-olds have “comebacks.”) I’ve written about this film (and Wood in it) elsewhere, but it must be said again: IT IS A MARVEL. A hysterical, yearning, roll-on-the ground marvel. The French translated it into Fever in the Blood. That’s what I’m talking about.

Sidenote: I bought my best friend the poster for her birthday, and now it’s framed in the guest bedroom where I’m currently lazing through my Seattle summer, and I wake up every morning and read the text on the side and get chills.

And I look at the image below and suddenly it’s wide-eyed and scary and dangerous indeed.

Now, Collins and Beatty were still engaged, but Collins was off shooting elsewhere, and as Beatty’s star rose, his need for an engagement seemingly fell. Or, who knows, they might have just figured out they had irreconcilable sleep schedules, or that only one of them liked black licorice. A planned wedding was called off just in time for the hoopla surrounding Splendor in the Grass, and its pile of Golden Globe and Academy Award nominations, to crest. Oh, and for a hot relationship with co-star Natalie Wood to develop, all RPattz and KStew-style. Their relationship apparently apes that of their onscreen characters in Splendor, all rollercoastery and emotional, although I bet they actually had sex instead of going crazy and/or becoming poor.

Wood and Beatty attend the Oscars arm-in-arm, surrounded by cameras, and when Wood loses Best Actress to Sophia Loren, gossip maven Hedda Hopper exclaimed “Natalie Wood was robbed! But at least she got the nicest consolation prize — Warren Beatty.”

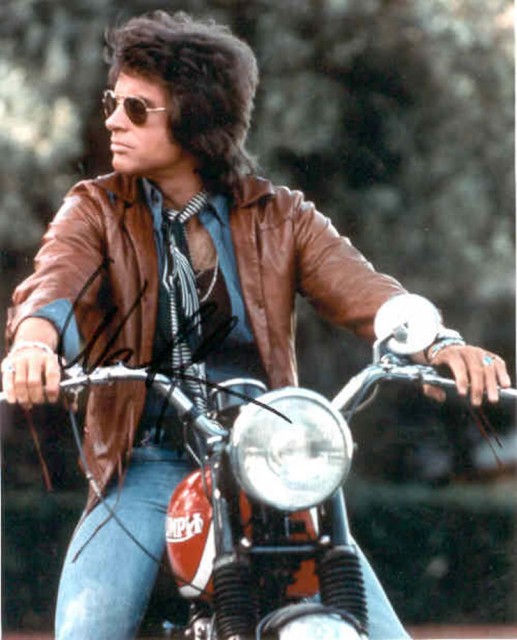

Around this time, Beatty began to establish the beginnings of his image as a fresh-faced womanizer. Already, there’s something about the way he looked at women, and the way that women blossomed under his gaze. You see it here, when he’s pretty much the hottest man ever to wear glasses:

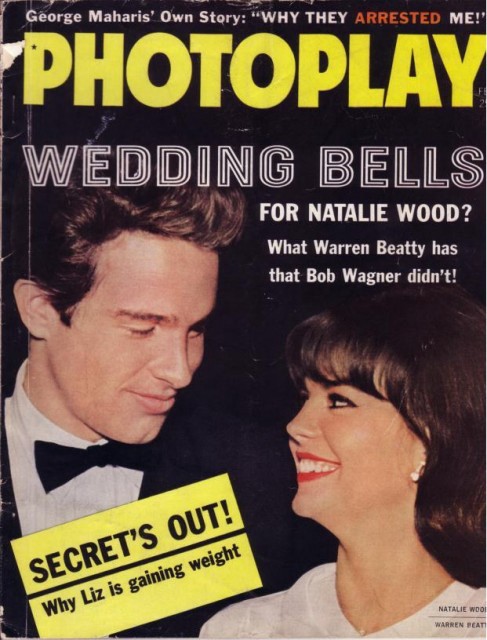

And again here, when Photoplay tries its best to insinuate that Beatty has a huge package:

Beatty was all sorts of visible, and he appeared in three high profile projects before the end of 1963. The problem, then, was that all three of these films — The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, All Fall Down, and Lilith, director Robert Rossen’s last film — were disappointments. Lilith has aged well, and was underestimated at the time, but Beatty was increasingly frustrated with his inability to make good on the promise of his turn in Splendor. He would barrage directors with questions, growing increasingly frustrated with their lack of decision or direction. He was spending his star capital, and it would run out soon.

His obsession with knowing everything that was happening — everywhere, all the time — grew. After much back and forth that reminds me much too keenly of my sophomore year in college, Beatty and Wood broke up, sparking a string of one night stands on his part — seldom for sex so much as for connections.

What’s fascinating is how Beatty combined the masculine prowess associated with promiscuity, yet used it the way that we usually think of women and sex in Hollywood: to get ahead. He slept with co-stars, slept with producers, and when a female critic panned Lilith, he purportedly slept with her, too.

After some testing of the waters, Beatty was linked to Leslie Caron — she of An American in Paris and Gigi Kewpie-doll fame. Caron was married to Peter Hall, the director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, with whom she had two small children. But Beatty was no (legitimate) home-wrecker: Caron and Hall’s marriage had been long-strained, with both of them living apart to pursue their respective ambitions. As Hall himself admitted, “by 1962, there wasn’t much left but resentment.”

Caron in full Gigi mode.

Caron was six years older, a mother of two, and Beatty was apparently totally smitten. According to Caron, “he was a very sensitive, private person and not really comfortable in a crowd — but he played the part of a playboy movie star conscientiously, as if it were an acting job.” And he was horribly insecure: he allegedly once woke Caron at 5 a.m., worried that “You’re sleeping. You’re not thinking of me.”

Not 5 a.m.

Which is another way of saying that Beatty was essentially becoming The Worst. He had become increasingly frustrated with his backseat role as leading man, and as his films continued to lose money, it seemed clear that audiences didn’t want to see Beatty onscreen. It was almost as if they were wary of him, or only wanted to think about him, not actually see him — otherwise how can you explain the fact that no one went to go see the clearly awesome Mickey One?

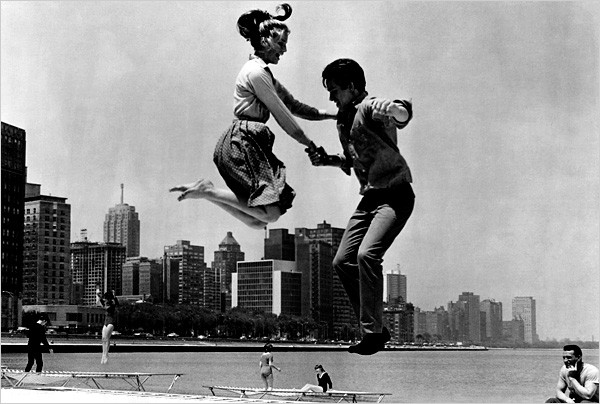

Comedian targeted by the mob? American attempt at nouvelle vague? Warren Beatty in a role intended for Lenny Bruce? Supposedly Polish? Surrealism meets trampolines?!? This film is disaster, but it’s a beautiful disaster, even if Beatty himself admitted that it was “unnecessarily obscure,” which is kind of how I describe 95% of MA thesis topics.

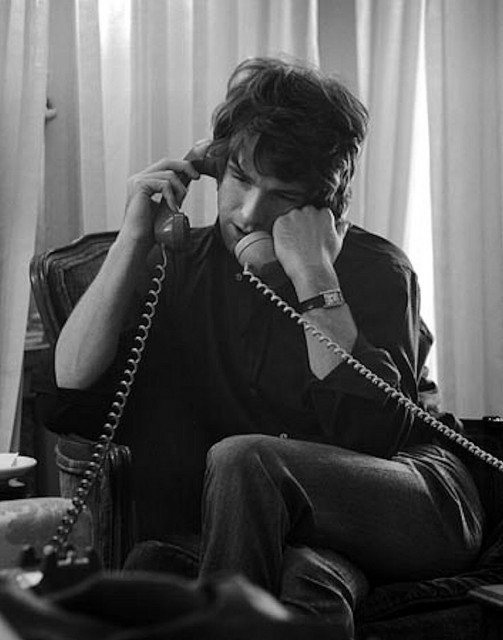

Somewhere around this time, Beatty began to develop an amazing ability with the phone. Meaning he was constantly on it — but not in the annoying, always-be-closing stockbroker sort of way. More the purring, sex-on-the-line sorta way. He’d wake up, day or night, and get on the phone, and call everyone he knew, starting each conversation (with a woman) with “What’s new Pussycat?”

Various people in Hollywood figured out this was happening, that it was awesome/farcical, and producer Charles Feldman started working with Beatty to develop a film quasi-based on Beatty’s philandering lifestyle. The title, natch, would be What’s New Pussycat? To help flesh out the script, direct, and take a supporting role, the two hired an unknown talent by the name of Woody Allen.

What’s New Pussycat seemed to be Beatty’s way to show that he had a sense of humor — and reactivate his star image in a way that wasn’t just sleeping with famous women. But Beatty sent Feldman dozens of telegrams questioning every detail of the production — we’re talking a teenage texting level of telegrams — that drove the producer batty. They disagreed about casting, about the direction of the plot, about characterization … and, worst of all, Allen was making his own character more and more crucial to the film, effectively giving Beatty second billing in his own production.

The whole thing is so Woody Allen I can’t even stand it. Then, the final straw: a gossip column claims that Caron has been cast in the lead — which Feldman archly opposed. Feldman becomes convinced that Beatty is trying to outmaneouver him and boxes him out of the production. The movie, featuring Beatty’s own f-ing catchphrase, proceeds forward — with Peter O’Toole in the lead. It makes a fair amount of money. But Allen “hates every frame.” The experience so burns both Allen and Beatty that from that point forward, they essentially won’t let another person touch their work.

Enter Bonnie and Clyde. Or, rather, enter the build-up to Bonnie and Clyde.

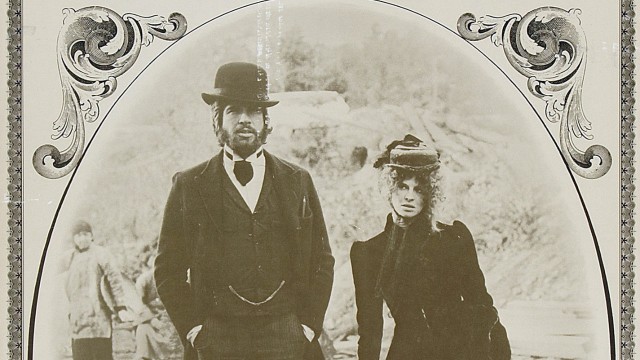

Caron and Beatty are hanging out in London, and Beatty hears that Francois Truffaut, he of The 400 Blows and Jules et Jim and, you know, all of those other French masterpieces, has an adaptation of Fahrenheit 451 in the works. Caron sets up a meeting for her overanxious boyfriend and Truffaut, but Truffaut says no way, mon ami, but maybe you want to develop this other gangster thing? It’s called Bonnie and Clyde, give it a shot, you and your girlfriend can play the leads.

Beatty dithers over buying the script, thinking that Westerns are washed up — the stuff of television and B-movies. But Caron tells him to stop being a doofus: it’s a gangster movie, stupid. Beatty buys the script for $75,000, but tells Caron that she’s too French to play Bonnie. He wants Bob Dylan for Clyde. Maybe his sister for Bonnie? But then he decides that he wants to play Clyde, which means that his sister TOTALLY CANNOT PLAY BONNIE.

He offers it to (still good friend) Natalie Wood, but she turns it down. So did every other female star in Hollywood: Jane Fonda, Ann-Margaret, Sharon Tate, the list goes on. In the end, it was Arthur Penn, who Beatty had wrangled to direct, who discovered Faye Dunaway on the stage. She was Bonnie; Bonnie was her. The rest is history.

Now, when was the last time you saw this film? Was it in my college film history course? Was it with your dad sometime in high school? Whenever it was, it was too long ago. Because this film is perfect.

I would show you a clip, but all that’s really available is this masterpiece montage set to Bon Jovi’s “It’s My Life” and this one of Jay-Z and Beyonce going south of the border with bikinis and berets.

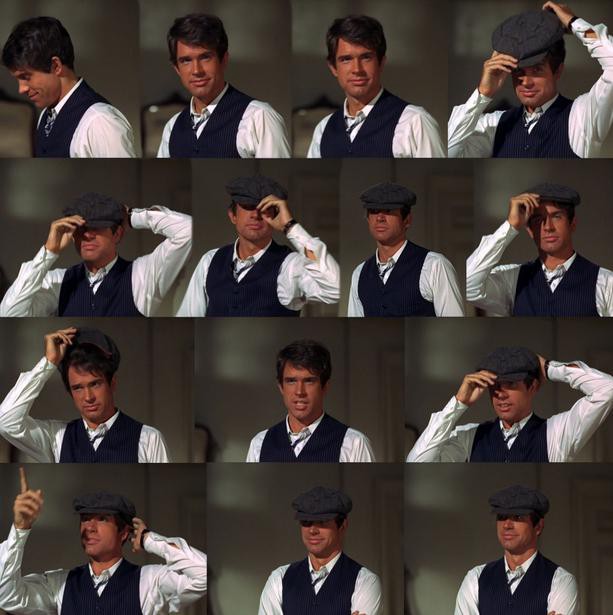

But maybe this will entice you?

Or maybe this?

Beatty was in his element: he was controlling the film, and he was playing the role he was destined for — a hapless, affable, cocky schmuck. He was impotent yet charismatic — when you see how Dunaway looks at him in the beginning shots of the film, you understand exactly why she leaves her life to be with a man with little more than a gun. Part of this is acting; part of this stems from the very real fact that unlike every other situation in the last ten years of his life, Beatty didn’t sleep with Dunaway. The frustration is palpable.

Beatty and Dunaway’s performances underline the ennui, oppression, and hopelessness of the summertime in the heat of the Depression. There’s a poetry to this film that has only expanded with age, plus the commentary on the formation of public images, well, as you know, that’s the sort of incisive cultural commentary that AHP loves. I can’t get enough of this film, and while Dunaway, Penn, Gene Hackman, and even Estelle Parsons, the single most annoying film character of the second half of the 20th century, have a lot to do with it, Beatty was its mastermind.

As douchey as the preceding 2,000 words have made Beatty sound, this film — and the courage it took to convincingly portray an impotent man — defined his career. No longer was he Beatty, the man no one wanted to watch: he was the man everyone wanted in everything.

But Bonnie and Clyde almost didn’t even get seen. You can read a lot more about why in Peter Biskind’s various books, but here’s the short version: Warner Bros. agrees to fund and distribute the film, but really doesn’t think much of it. There’s also the matter of the visceral violence at the end of the film, which, despite the existing holes in the Production Code, was still something else altogether. All the major film critics think it’s an abomination, including Bosley Crowther, the old man of the old Grey Lady. Exhibitors are cautious, and it makes next to nothing.

OH BUT WAIT ONE SECOND, because Pauline Kael, then just a staff writer at The New Yorker, writes a rave to end all raves, effectively forcing other critics to reappraise the film or get the hell outta town. “Bonnie and Clyde is the most excitingly American movie since The Manchurian Candidate,” she wrote. “The audience is alive to it.” She was totally right.

The Times fires Crowther for being such a moralizer, and the film goes on to gross $70 million — a truly phenomenal number for 1967, especially given that it was made for $2.5 million. And the story gets even better: because Warner Bros. had put so little stake in the film’s success, they agreed to give Beatty 40% of the film’s profits. That’s some Mel Gibson-Passion of the Christ money right there.

And enough for Beatty to make whatever movie he wanted, with whomever he wanted. For DECADES. That is some serious capital — the kind we haven’t really seen since Gibson’s own flame-out.

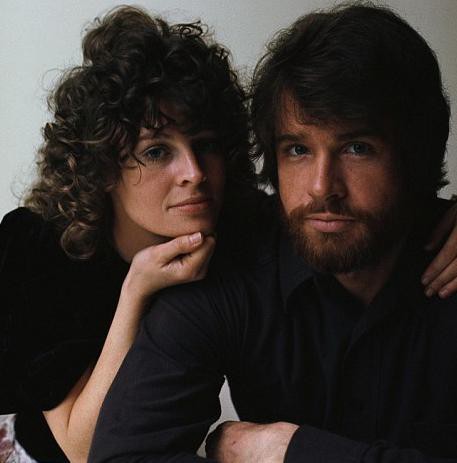

But while Gibson chose to use his star capital to entertain the Christian fundamental base, Beatty bided his time. According to lore, he sees Julie Christie, still hot after Doctor Zhivago, meeting the Queen, and falls for her. But Christie was having none of it: “I was always attracted to people who appeared think you were a dross, people who I felt thought I was really stupid and frivolous, and who didn’t give a toss what I looked like.”

In other words, Christie f-ing loved hipster boys. She was engaged to a British artist, and thought Beatty the equivalent of a state school frat boy. But he managed to get her to come to dinner, and surprised her with his intelligence. He stays in the background, biding his time until she outgrows her hipster boyfriend and moves back to L.A. They move in together; have a lot of sex; go full counter-culture. Really just adorable stuff.

The soprano sax! I DIE!

(Did I mention that he broke up with Caron? And slept with several dozen women between her and Christie? Sorry, I was getting bored with listing hook-ups.)

For all his love of Christie, Beatty couldn’t let go of his telephone. When Christie was off shooting elsewhere, he’d pick up the phone. Peter Biskind tells it best:

Never identifying himself on the phone, speaking in a soft, insinuating voice rarely raised about a whisper, flattering in its assumption of intimacy, enormously appealing in its hesitancy and stumbling awkwardness, he asked them where they were, with whom, where they were going next, and would they be sure to call him when they got there. His appetite for control and thirst for information were as voracious as his appetite for sex, and it seemed that inside his head was a GPS indicating the whereabouts of every attractive young woman in Los Angeles.

Maybe because I’m allergic to the phone, I can’t quite understand the appeal. Do you think he’d be today’s version of a good text messager/emailer? The kind who manages to be witty and addictive, who replies just often enough, who can be funny and beguiling and hot and smart all at once? If so, then okay, I’m on it.

Between GPS tracking, Beatty looked for his next project. He could be very, very picky. There was the unfortunate mess of The Only Game in Town, but Beatty was just there to co-star with Elizabeth Taylor. (Lucky You, starring Eric Bana and Drew Barrymore, is a remake of this film. That should tell you what you need to know.) Oh, and $, sometimes referred to as Dollars, with Goldie Hawn, is maybe just as fun as Oceans 11, but with better music. I can’t really tell you; I haven’t seen it since it aired on TBS when I was 10.

Amid this mess, Carly Simon writes “You’re So Vain.” She refuses to reveal who the song is about. Beatty, having dallied with Simon at some point in the past, thinks the song is about him. He calls Simon to thank her. Obviously.

The Only Game in Town and Dollars were relative shitshows, but then there was the melancholy marvel of McCabe & Mrs. Miller. If Beatty had only made this film and Bonnie and Clyde, he’d still be among my favorite stars. He returns to the bumbling, wide-eyed quasi-naif, and watching Julie Christie out-man him at life is just so amazingly pleasing. I forgive him everything. And that last scene! That last, heartbreaking scene! Screw you, Leonard Cohen soundtrack! I’m falling to pieces over here and I’m only watching the trailer!

Plus Julie Christie, HOT DAMN.

Granted, this film might not be for everyone — especially if you are the type of everyone who doesn’t like Robert Altman or genre revisionism — but oh, it is for me. Beatty apparently hated Altman, as someone with the sort of obsessive, questioning personality like Beatty probably would if paired with the nonchalance of a director like Altman. Christie loved Altman. Cue break-up with Christie.

Throw in some Parallax View, a few years off to campaign for George McGovern, and you find yourself at Shampoo, which, along with Burt Reynolds on a bear rug in the pages of Cosmopolitan, is one of the true great cultural artifacts of the 1970s.

Beatty was one of those guys who stays friends with all of his exes. Which is part of how he convinced both Goldie Hawn, a “friend” from his $ days, and Christie to co-star in a movie about a male hairdresser who pretends to be gay … but is really bedding all the girlfriends and wives in town.

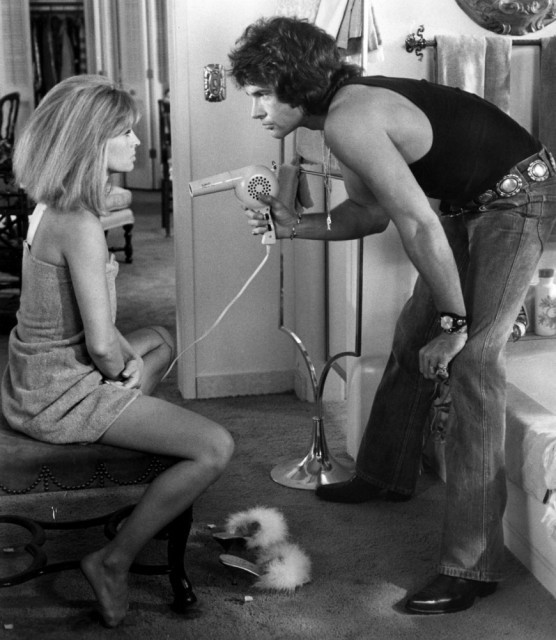

It’s a beautiful farce, and not just because of outfits like this one:

And haircuts like these:

Beatty was, as usual, in full micro-management mode, pissing everyone off and making the director, Hal Ashby, adhere to his vision of the film. (Anecdotal evidence has Ashby high and off in a corner while Beatty actually directs the film.) Once it wrapped, everyone in Hollywood thought it was going to bomb. It was too much, too offensive — when Julie Christie’s character goes “under the table” in the last act of the film (read: starts to give someone a blow job) a full third of the test audience walked out. It was blowing the sexual and political hypocrisy of the Nixon years out of the water, and execs, agents, and others too close to Hollywood didn’t know what to do with it. They were, in part, the ones being satirized.

But the critics loved it. So did everyone else. It was a monster hit, and reinvigorated Beatty’s image. Here was a man playing a manwhore: a hapless, frustrated, confused manwhore who can’t keep his girlfriends, mistresses, and mishaps in order. Beatty satirizing Beatty, or at least the image of Beatty. With a line — “I don’t fuck anyone for money, I do it for fun” — that only further defined him. It’s an underrated performance in an underrated film, and you should probably watch it right now for free via Amazon Prime, if only to see how much you should be mourning Kate Hudson’s recent movie choices. Plus the minidresses, the beautiful minidresses!

And the hairstyling, it really is pretty great. When Beatty tells Christie that he wants to cut her hair, it’s such a gesture of unadulterated affection.

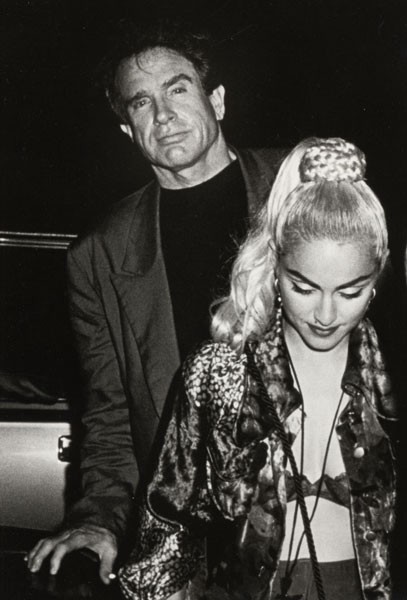

And so things went for the next 20 or so years: a much-belabored film interspersed with new romances. He successfully wooed the Academy with Reds, which I find somewhat tedious and not nearly as revelatory as Bonnie and Clyde, and bombed out big with Ishtar. He spent years on the overkill that was Dick Tracy, started dating Madonna, and looked so incredibly embarrassed in her Sex movie.

In many ways, Beatty and Madonna were a perfect match: both keenly understood how sex intertwined with their respective images, and how to exploit those images in a way that would endure. They were, and remain, survivors. But Madonna’s particular brand of showmanship was a better fit for Beatty circa 1970, and my guess is that, among other things, she might have made him feel old. Or at least undersexed, if that is even possible.

And then there was Bugsy, Annette Bening, an actual marriage, a rather pulseless remake of Love Affair, and four children. With Bullworth, he evidenced that he was not only still a star, but still very much engaged in making smart, incisive satire.

It should be clear that Beatty could be an asshole. Or, perhaps more precisely, a real pain in the ass. Barbara Walters once named him the most difficult man in the world to interview. He could be withholding and cagey, exacting and relentless. But so could Orson Welles, and we remember him for his movies, not his love affairs (of which there were also many).

Beatty was certainly a womanizer, and probably (most likely) a sex addict. So were lots of stars of Classic Hollywood. The difference was that sex became part of his image in a way that it never could for his antecedents. Beatty’s image encapsulated the masculine role in the sexual revolution — the casualness, the sheer proliferation of partners — and the accompanying emotional distance and unsated hunger. In his films, and in interviews, you sense both: the distance, the hunger, and the logical yet absurd conclusion that a life of fulfilled desire was, ultimately, unfulfilling. In subtle, unspoken ways, his image spoke truth to the lie of the American sexual revolution: namely, that free love brings freedom.

I’m not suggesting that Beatty found monogamy and somehow found himself, or even found happiness. (For what it’s worth, he did claim that “for me, the highest level of sexual excitement is in a monogamous relationship.”) Yet the problem with free love in America — and with Beatty’s image in America — is that it grinds against more than 200 years of puritanical sexual conservatism.

Because Beatty’s image is overtly sexual, it must morph grotesque: suddenly he didn’t just have sex with hundreds of women, but thousands. He becomes an object of fascination and repulsion: he’s feminized (manwhore! slut!), made abject. And, as has occurred with so many female stars, the focus is not on his work — which really is staggering — but what his body can and has done. If you watch Shampoo closely, you realize that’s what it’s really about: all Beatty’s character wants is to prove himself, to get out from underneath his condescending boss, to cut a truly beautiful head of hair. But no one will stop fondling his package long enough to let him.

Now, I realize that Beatty was not some exploited female starlet. He did no small amount of exploitation of his own reputation, not to mention women’s affections and his position of power. But the scandal of Beatty’s image is that a man who really just wanted to make beautiful, incisive films, get worthwhile candidates in office, and have a lot of sex along the way is remembered almost exclusively for the last of those three. Sex becomes Beatty.

As for me, I’ll remember Beatty best for his portrayals of sexual frustration — the breathless desire of Splendor in the Grass, the wide-eyed bewilderment at the heart of his Clyde. Sex doesn’t become him; it beguiles him. Fifty years from now, scholars will look back and consider not what Beatty’s image was, but how our twisted reception of it illuminates the hypocrisy at the heart of American sexual values.

Previously: Dorothy Dandridge vs. The World.

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.