Centers of Gravity: In Conversation With an Ex-Gymnast

by Sarah Marshall

Chelsea Bieker will not be going to London this year. A forme competitive gymnast and current coach, she’ll be spending the summer teaching freshman composition classes at Portland State University, where she finished her MFA in fiction earlier this year. Though Chelsea currently spends most of her time grading papers and writing short fiction about murderers, barflies, teenage prostitutes, and the good people of Fresno, California (her hometown), gymnastics still has a place in her heart, and she was kind enough to share her thoughts and memories with me over a few YouTube videos.

Sarah Marshall: What’s the first gymnastics video you think of when you remember Olympics of the nineties?

Chelsea Bieker: I think obviously my mind would go to the ’96 Olympics and the team competition, but I had sort of an early fascination with Shannon Miller, and I have early memories of watching her even before that. Anything with Shannon Miller was just my favorite.

Do you remember watching Barcelona?

I think it was Barcelona. I would have been only five, maybe, but I definitely remember seeing her perform before ’96, and knowing who she was.

And it was weird that she was in two Olympics, too, right? Because most people just do one and then they’re done.

She tried to come back for 2000 as well, and then had to pull out because she hurt her knee. And I remember I used to order documentaries and videos, because back then you couldn’t just Amazon something, so I would send in for things. I had one that showed her training center and her really young, and Steve Nunno, her coach. I think she was probably the one I fixated on the most.

Let’s watch some Shannon Miller.

It always intrigues me to see them when they’re literally just children, and they can still do all these incredible things.

That’s one of the things I wonder about, because I was reading about how Bela [Karolyi, who coached Nadia Comaneci, Mary Lou Retton, and the “Magnificent Seven” in 1996] would go look at kindergartners in Romania and pick out girls to train. How would you pick out a kindergartner, or even an eleven-year-old?

Well, it’s funny. I’ve coached for probably six years, and I’ve seen three-year-olds with muscle tone and the ability to have body awareness. I think you can be born with that.

So how do you find the body awareness? Is it more of a mental connection between what they want to do with their bodies and what they can do?

I think you can tell with the children where, if you give them an instruction regarding their body, like “straighten your legs” or “make sure your arms are by your ears,” they’re able to make those adjustments quickly — whereas maybe a child without that body awareness naturally built in will take longer, and you might have to actually put their body in a position, because verbal instruction doesn’t work. And then it’s just kind of developed through training, and some are more visual learners, so they can watch the skill first and then perform it, and some need to be taken physically through that motion. So I think it’s just a little different for everybody. But I would imagine these girls that are in the Olympics had that kid of awareness and control really early on. So, I guess if Bela were scanning a group of kindergartners, he would look for the one that could regain balance quickly, or find her feet, or understand where her feet are when she’s upside down, or just has an early grace that a lot of kids don’t have. But it does exist. I’ve seen three-year-olds that can do skills that most adults could never do.

So now we’re watching Shannon’s floor exercise. How do you describe this, in terms of comparing her to other gymnasts, or to what kind of gymnastics we’re doing now, and if we’ll be looking at something different in London?

I think with Shannon Miller something that always has stood out with her, and set her above the rest, is that even at an early age she just has an extreme control, and she has extremely good extension. Her toes are completely pointed, there’s never a bent leg, she never really breaks that form — even if she falls or something, she still is kind of in position. And, honestly, I’ve rarely seen Shannon Miller fall. I can’t even think of a time. She’s not hasty, and she has an even, measured quality about her work, I think.

And looks like she’s not really nervous about what she’s doing, and is just focusing on her movements.

Yeah. Just really fluid — and her toes are completely in line together going over. You could watch her from pretty much any angle and she’s gonna have good form.

How much have you been following the change to the code of points, and the fact that you can’t score a perfect 10 anymore? How influential has that been?

I’m not really sure of the last time a gymnast scored a perfect 10. It started with Nadia Comăneci, and since then I’m not sure. I know that when I started following it and I knew all those details, kind of in the later ’90s and early 2000s, no one was really scoring 10’s anymore. Even though it was still possible, the level of difficulty had gone up so much from Nadia’s age, and it wasn’t really a possibility anymore.

And going from Shannon, to Nadia, I think that they have similar styles and are both sort of elegant and have the same … completeness, I guess, but would you say that the level of difficulty is substantially more with Shannon?

Shannon’s routines are much more difficult than this, but you also have to consider the equipment that Nadia’s on versus the equipment that Shannon was on, because this beam isn’t gonna have any reflex in it, and it’s pretty much just a piece of wood — whereas the beams that we have today and the beam that Shannon was on are covered in suede, and the legs actually give to provide a tiny bit of spring and landing support. What Nadia’s on is the equivalent of just being on a block of wood, and to do that on a block of wood is extremely hard — but of course not as hard as Shannon’s. But for this day and age, this would have been considered a really top difficulty routine. Beam technology has gone up and up and up, and today you have the grip of the suede, you have the give of the legs, the padding, you can do harder things on it. But what they were working with, it wasn’t really possible.

The human body hasn’t changed that much in the last 20 or 30 years, so it feels like it’s about equipment, but also about believing in the potential to do something.

I think you’re right, and I think about watching some of the first routines in the Olympics, once gymnastics was a sport, and today we would call them extremely easy. It is also a mental progression toward harder skills, because at that point I don’t think some of the things we’re doing in 2012 were even imaginable yet.

What are some of the things that we’ll be looking at in this Olympics that would have been unimaginable in 1976?

I remember the skill that, when I first saw it, I thought “Whoa, I never thought that anybody could do that before,” was the full-twisting back salto on the beam. And I think the first time I saw it was close to the 2000 Olympics, and now everybody’s doing that — but then there were two girls that could, and they were at the top of their game.

And it’s become something that you have to do to be competitive?

Almost, yeah. I think what I’ve noticed, watching gymnastics again, is that the combinations they’re doing now are much more advanced — the skills that they’re connecting with one another. And if they miss those connections that’s actually a big problem. They might do the back full tuck on the beam, but they’re gonna go right into another one, and if there’s a pause or a wobble in between they’re gonna lose that whole series. So everything’s now in a series. I noticed that, on the bars, everything has to land in a handstand position at the end, so not only do they have to complete the skill but they have to land in a perfect handstand, or it’s like they didn’t even do it.

Let’s watch some of the Olympic trials.

This is another thing I was thinking about, because if you look at gymnasts in the ’70s or even the ’90s, obviously they’re incredibly muscular but they’re very thin, and if you look at Gabby Douglas you can see her muscles really clearly — she has huge biceps and looks less, I guess, streamlined.

Less waify.

Yeah. And less girlish, too, because I think she’s only sixteen but she looks very adult. Do you think that that’s something that’s also changed?

I think that the body type you have to have to be able to do this routine, you can’t really be a waif anymore. You have to have that kind of muscle. The strength component is huge. And these girls — there were so many eating disorders and so many problems with weight, and this idea that you needed to be thin to win, thin to be a good gymnast, I’m sure that that is still going on, but I would say there’s really been a push toward thinking “No, I don’t care if I’m thin, I want to be strong, and whatever I have to do with my body, even if I have to bulk up or look larger, that’s fine.”

And that’s become more generally accepted?

I think so. I think you see that just in the way they look. They don’t look starved to me. They look pretty healthy, and I would imagine that that’s true. I mean, we don’t know, but back in, maybe, the ’70s, routines weren’t as challenging, and they maybe didn’t need to do such strenuous things, so they could be that skinny-skinny.

I was thinking about that because I just finished reading Joan Ryan’s Little Girls in Pretty Boxes, which was the big mid-nineties gymnastics exposé. And it does make it seem like gymnastics is just this endless array of miserable, starving, suicidal girls, which I think is an overstatement. But one thing it mentioned that I did think was interesting was Kim Zmeskal’s performance in Barcelona and how she had a stumble on the balance beam. The claim that Ryan made was that it was because she had been so starved and so pushed beyond her limit, and just couldn’t get it together for the games. Someone also suggested that she just peaked a year too early, and that ’91 was her peak year and that it was sort of over by then.

Did she come out with an eating disorder?

I didn’t read anything about that. And obviously she wasn’t spoken to for the book, so you can’t really say.

I remember more Christy Henrich, because she died of an eating disorder, but Kim — I think it was peaking. Any gymnast hopes to peak during an Olympic year. And it’s not a sustainable sport. What she is doing right now [in the video below] — to continue that level, to be where she is at this moment, it’s hard to sustain that. It’s nearly impossible, and your training kind of goes in waves. They strategically train to peak right now. I think a similar thing happened to Vanessa Atler. I would compare her to Kim Zmeskal, where she was supposed to be the one for the 2000 Olympics, and she ended up not making the team.

The other thing Ryan talked about was her main gift being her toughness. Obviously she was an amazing gymnast, but her being able to push herself harder than other girls, and to take more pain in stride — I guess percentage-wise how much of that would you say is required, versus natural ability and talent and potential?

I would say that your mental relationship to the sport is 60% of the game. You see a lot of girls with a lot of natural ability, and maybe not the right attitude or the right mental capacity to have that toughness or stick with it in that way, and sometimes maybe a girl with less natural ability but more of a drive and more of a willingness to sacrifice will end up being the better gymnast. And probably the girls we see here are the rare mix of both natural talent and mental ability.

It’s kind of the same with writing.

Yeah.

Although I think gymnastics is harder.

Well, it’s funny. I remember being a gymnast and my coaches always saying “We want to get as much as we can out of you before you hit puberty. Because once they hit puberty, they’re outta here.”

Is that in terms of body changes, or attitude changes?

Kind of both. But I remember it happened for me really starkly. I was never scared to try anything, I just trusted that my coaches would catch me. I just didn’t think things through. The consequence piece isn’t there, and somewhere around puberty suddenly you’re like, “Wait, I could break my neck. I don’t want to do this.” And that’s when those mental things start coming into play in a way that they wouldn’t for a child.

Let’s talk about your gymnastics experience. How old were you when you started, and why did you start?

I remember going to birthday parties where some of the girls were in gymnastics, and they could do things on the grass — kick over from back bends or walk on their hands — and I just wanted to be able to do what they were doing. The first time I saw gymnastics on TV, I was just mesmerized. I thought, “I need to do this also.” It was just that simple. At the time I lived with my mom, and I would beg her to take me to classes, like “Please sign me up.” And this was when I was around six and seven, and she was like, “No, it’s too dangerous. I don’t want you doing that. There’s no way.” And so I remember she bought me a leotard, and I would watch it on TV wearing my leotard, and I would try to teach myself things. And I actually entered my first gymnastics class a few years after that, and I could already do handstands, cartwheels, the splits. So I had taught myself some things, and I asked girls in school who were in classes to tell me what they were learning. I was just really obsessed with it, and I wanted to know everything that I could find out.

And did your mom finally fold?

No. I moved in with my grandparents, and the summer before I moved in was the summer of the ’96 Olympics, and I stayed with them for a few weeks when it was playing, and my grandma is someone who loves the Olympics. We sat down every day and watched it, and she could see that I was extremely obsessed with the gymnastics part, and I would tell her, “If I could just take lessons…” We just really enjoyed it together, and when I moved in I was like, “Okay, well now I can beg you guys to do this, because mom’s out of the picture.” And she was really supportive of me, because I think she could see that I had a serious interest in it and really wanted to try it. And within a week of living there she took me to the nearest gym and signed me up for a class once a week, and within a year later I had worked my way up to a competitive team there and started going to little meets. I just loved everything about it, and she was really into it for me.

What were your favorite things about it?

I think I early on really liked doing the floor exercise, just because I liked to dance, and I wasn’t the fastest or strongest athlete, so a lot of my strength was from more of the artistic component — like the dancing component, the leaps, that stuff, so I was naturally drawn to it. I also really liked the bars. When I was younger I think I was an average height for my age — you know, I’m an average-sized woman, height-wise, but for a gymnast I’m really tall, and at the beginning that didn’t seem to be that much of a problem, but in eighth grade I shot up to about 5’4”, and it was disastrous because I had to kind of relearn certain skills to match my height. Your height changes everything about your center of gravity, and you make rotations slower. And that was really hard, but even then I didn’t want to stop.

That has to be really confusing, too, because stuff that you used to be able to do you just can’t do anymore.

Oh, yeah. It was really hard, and everyone seemed to be praised for being short, so I always felt that the short girls on the team were somehow ahead of the game because they were the right size. But it was also luckily at a time where Svetlana Khorkina was getting a lot of attention, and she became the world champion.

And she’s about 5’5”, right?

She’s really tall for a gymnast, and really skinny and long, and so she became sort of my idol at that time. Like, “See, everybody, it doesn’t matter, I can be Svetlana.”

Let’s watch some Svetlana.

She was one of my favorites.

I think it’s nice to have exceptions for all of the general rules. I think there was a Russian gymnast who competed in five Olympics, and won a medal in her late twenties. And [in reference to Khorkina] the difference is amazing when you look at her.

So, she’s considered extremely tall for a gymnast, and she looks really tall on the mat compared to what we’re used to seeing, but I remember being really excited about her.

So after your growth spurt you kept doing gymnastics. When did you stop?

When I was fifteen I was a level nine. You’re put into levels — I believe it’s still the same, and the competitive levels are level four to level ten. And once you’re a level ten you can petition to become elite. So the girls we see on TV, they’re all elite, pretty much the top of the elites. Level ten was where I was hoping to go, like a lot of girls on my team — I mean, we didn’t have Olympic fantasies at that point, and we were trying to do it for college teams and to get scholarships. Most college girls were level nine or ten. And so I was level nine when I was fifteen, and I broke my arm, and so this surgery [pointing at a scar on her forearm] had to happen, and it was a really bad break, and it was right before the competitive year where I would have probably been in contact with people from colleges. It was supposed to be a really great year, and then that happened. So I would go into the gym every day with my big cast and do conditioning, and just stay there for hours and kind of do what I could with one arm. And then when I started training again, it was just a much longer process than we thought. I had a lot of nerve damage to my hand, and obviously you need your hands on the bars. And I found quickly that it was not going to be the same. I had lost a lot of strength, I couldn’t bounce the same way off my arm anymore, and in the short time that I stopped training as hard as I was — because I would train at least six days a week, at least four hours every time, every week — I essentially went through a really quick puberty in that time. Everything was different. I looked like what I think of as a normal teenage girl, and to me that was horrifying. It was just the worst thing that could ever happen. It was almost overnight — because when you’re that active your body’s not gonna start shooting off hormones to develop. So I just had to be like, “All right. This is it.”

And you had already gone through puberty, and now you had to do it a second time.

It was terrible. In gymnastics there’s a small window, you know — sixteen, seventeen, eighteen, you’re getting up there. You’re already getting old. And at the same time I had a fracture in my leg that was not being attended to at all — we found out later that it was a hairline fracture down my whole shin. I had just been taping myself, and I was just broken. It wasn’t working anymore. So then I started coaching at the gym.

Do you think that made it easier to transition, to still be working in gymnastics and help girls get started with it?

I think it would have been really hard to just stop everything completely, and I had a really close-knit team and the time, and so coaching in the same gym was really good in that I could still see them on a daily basis, and still feel close. At the same time it was really difficult to watch them go on without me, or feel that I was now just — I had put my whole life into that, and then that was it. Like, there’s no parade for you at the end, it’s just over. And I think for a while I wasn’t really sure what I was doing, or what I was supposed to do. I never cared much for school, and that was kind of what I was banking on, and then it’s like “Figure out another plan.” But I think it did help overall, and I found that I really liked coaching. I don’t know that you can coach gymnastics without having done it, and without knowing what it’s like. I recently started coaching a tumbling class, and I haven’t coached since I was probably twenty-two or twenty-three, and I realized that it’s probably always gonna be some part of my life. I think it’s good for me, even though I’ve had many moments where I think “I’m never walking in a gym again!” And I think overall the reputation of gymnastics has left that world where we think of anorexia and young girls oppressed and people being taken from their homes. That’s still going on in other countries, but I think that changes have been made in a lot of ways. I know that when I started, it was a big deal that the gym didn’t have a scale in it, and the coaches really prided themselves on it and told our parents “We’re never gonna weigh your kids. We don’t have a scale here. We’re not like the other gyms.” Because that was a time where that was really in the open, and gyms were getting a bad rap because they’d line you up and weigh you.

Do you think that people who ran gyms had to focus on remaking their image?

I really felt that. The first gym I went to never talked much about diet. The second gym I went to, when I was competing at a lot higher level, had a coach from Armenia who had been on the Armenian world team, and he would really bite his tongue a lot. I think that he knew it wasn’t okay for him to say some of the things he wanted to say to us. Sometimes he would slip, but he’d always say “Well, to you American girls I can’t say what I really want to say.” And we all kind of knew what that meant. He thought we were lazy and fat and not as dedicated as we should be, probably. I don’t remember anyone on my team having an issue with food. I know that they would line us up and we would stick out our legs and they would come by and kind of slap and check for muscle definition, and if we didn’t look like we were getting toned or looking a certain way, we knew about it. And the only time I ever felt pressured to lose weight or think about my weight in a different way was when I broke my arm.

And then it was while you couldn’t train the way you had.

Yeah. He spoke pretty good English, and I think what he knew at that time was “If she gains weight it’s gonna be that much harder for her to come back,” but what I heard as a fifteen-year-old was “You’re fat.” Because you’re fifteen, and when someone tells you “Really watch it this holiday, and stay away from the dessert table,” I just heard, “Chelsea, you’re fat.”

It’s interesting, because it’s about your body as an instrument and it needing to do certain things, and if it’s your body, then you don’t think of it that objectively.

Yeah.

How do you think having a background in gymnastics has impacted your writing, or the way you live now?

It’s funny, I was talking to Charlie [D’Ambrosio, a writing professor at Portland State]) last year, and somehow gymnastics came up. He was like, “Have you ever written a story about a gymnastics team or anything like that?” and I realized that it’s never even crossed my mind to enter that world fictionally. I’m not sure why — not to say that I never will. But I think as far as work ethic and what it taught me about life, I feel like in gymnastics it’s either you can do it or you can’t do it. It’s either “That was good” or it wasn’t good. And no one was sugarcoating anything for me at all — you got really conditioned to hearing everything you did wrong. A lot of coaches really didn’t compliment at all, and it was really just about what could have been done better. And you hear that on and on and on and on. It never stops. Nothing’s ever perfect. And then once you do it and you get a thumbs-up, it doesn’t matter because you’re onto the next thing. And maybe, in writing, I’ve been conditioned to take criticism, or to believe in criticism in a way that — it doesn’t stop me in my tracks in the writing process.

I think that is one of the hardest things in the workshop, and it’s sort of like having your body looked at objectively, as something that has to do things. And writing is sort of similar, because you’re writing a story about people who aren’t you, and it’s fictional, but you feel that you’re putting your heart and soul into it, and the people who are discussing it are discussing your soul, in a weird way. And of course they’re not discussing your soul, they’re discussing what it does as fiction. And if you’re keeping Shannon Miller off the 2000 Olympic team, it’s because she can’t do the things that she used to do, and not because she isn’t a great gymnast.

Yeah. I would say that would be the most direct association for me. It sounds really cliché, but it teaches you a lot of discipline, and you can’t make it to a certain level if you can’t take the criticism. And the whole thing is, you’re being judged — literally, in competition, you’re being judged, and every day at practice your being compared, you’re being chosen, you’re being kicked off.

And it’s on a numerical scale.

Yeah. So, I guess, the world of gymnastics has not been at the top of my list of worlds that I needed to explore in fiction, thus far. I think there’s been other worlds that have just come first, that I needed to figure out in the extensive way.

And that are more mysterious.

Yeah.

I guess that’s what makes gymnastics so great to watch, in a weird way, because everything happens in the open. I was thinking about how two of the big gymnastics moments were Mary Lou Retton’s vault and Kerri Strug’s vault, and the vault is about five seconds long, so you’re there for the whole story. And if you’re trying to talk about real life, you can’t see everything, and you can’t know everything that’s going on.

I guess in my head, every time I think “What would a gymnastics story even be like?” it always rings so cliché in my mind. Like, Tricia was tired before practice on Wednesday. And it’s just like, well, that’s not what I’m interested in right now. Not to say that the personalities that make up the gymnastics world aren’t worth writing about.

Sports stories are hard to do, too. And the problem is that the real stories feel like kind of a clichéd narrative — like, the Kerri Strug vault is, “She sprains her ankle and she has to land it on one leg.” I mean, if you made a sports movie about that, it would be so corny, but it happened.

Completely.

Let’s watch that, actually.

So here’s my last question, because I’m thinking about the narratives that happen in the Olympics, and that we fall in love with — and I did a survey recently about what Olympics moment everyone remembers, and the moment half of the people remembered was Kerri Strug. That was the big moment. And it was great, obviously — it was the moment — but it feels like Shannon Miller was the better gymnast, and she’s sort of been forgotten, because you can only have one defining moment per Games and Kerri Strug got it.

Well, it’s funny, I’ve seen Kerri in interviews actually say “I was always the one no one could depend on, and I was always the inconsistent one. And so it’s funny that, at the end, I was the one that came through.” And so hearing her say that was interesting to me, because I guess she almost has an awareness of the fact that perhaps she was not the best gymnast, and got that moment. Obviously, this was so dramatic, and it appealed to people on a really basic human level. Anyone — they don’t even need a knowledge of gymnastics to appreciate this moment. But I feel like people in the gymnastics community knew that, technically, her score didn’t even really count toward the Olympic gold. They’d already won at that point, they just didn’t know it. But I don’t think that deflates the moment.

And if it’s her personal story, it’s still an amazing thing for her to have done, and it’s the kind of thing that we want to do. We want to be that person, even if the team medal had already been won.

Yeah. And I think Shannon Miller was probably overall a better gymnast than Kerri Strug. But I guess Kerri got the last laugh. But it’s so funny hearing myself saying “Well, Shannon’s the better gymnast,” because everyone on that team is so incredibly talented and the best of the best, that it’s almost funny to figure out who’s the best of them. And it’s funny, working in gyms there’s always an anticipation of the Olympic rush, of kids who are gonna enroll. Because I bet you anything that this summer, gyms are prepared for enrollment to go through the roof. Because every kid that sees it on TV is like “Mommy, I want to do that.” I worked in 2008, and we did a summer camp, and it was just mayhem. Every kid wanted to go to the Olympics.

Previously: What We Will Be Playing in the London Games.

Sarah Marshall’s greatest athletic achievement is being able to complete this workout tape.

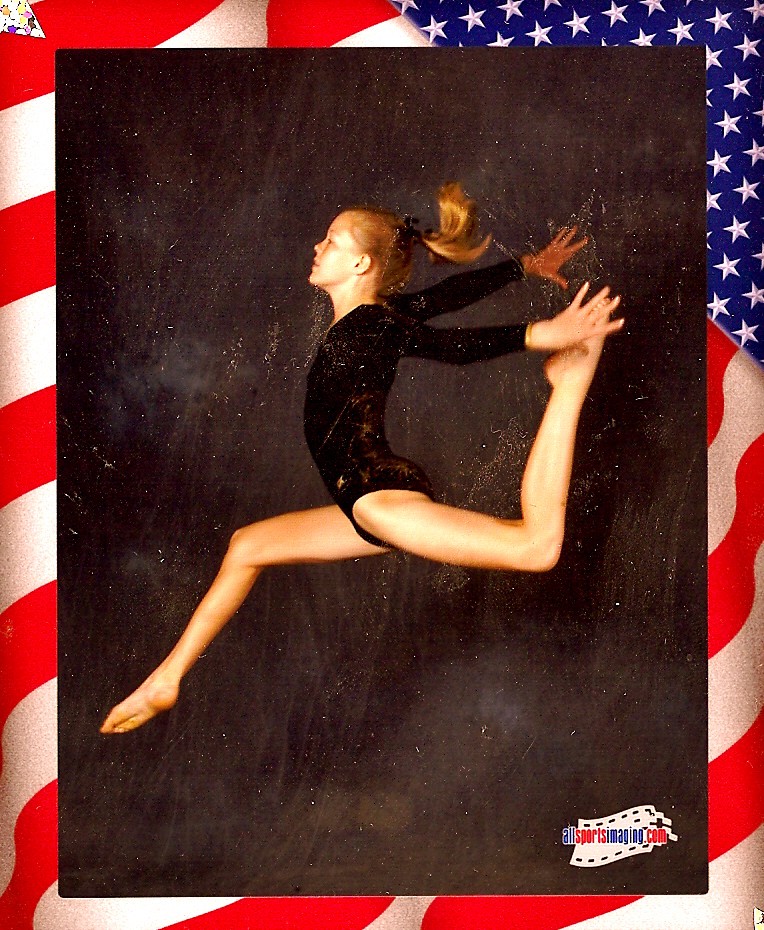

Photo by maxim ibragimov, via Shutterstock.