Scandals of Classic Hollywood: The Passion of Laurence Olivier

by Anne Helen Petersen

In the early ’40s, Laurence Olivier had everything going for him: he was widely regarded as one of the two best actors to ever grace the British stage, his film career had been set aflame by startling performances in Wuthering Heights and Rebecca, and his gorgeous wife, Vivien Leigh, had just pulled off Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind. He was also at the apex of his career as a stone-cold fox. And as half of the “first couple” of Britain, he was the closest that a born-and-raised Brit would get to bona fide Hollywood stardom. He and Leigh lived in flagrant sin, still married to other people, for months, years — and the press treated it like an open secret.

In this way, Olivier and Leigh were testaments to “true passion” narratives, and to their power to trump even the most potentially salacious gossip. But as would soon become clear, Leigh suffered from severe mental illness, and Olivier was unequipped to deal with the trauma of watching his longtime partner become unhinged in public view. After leaving Leigh for another woman, his image became that of a heartless if passionate cad, a man of great genius and great unkindness.

Olivier was born in 1907 in Dorkey, Surrey, where, as the son of a clergyman, he received a generous education, complete with wide exposure to the performing arts. By the age of nine, he was appearing as Brutus and betraying his countrymen in his school’s production of Julius Caesar. By all reports, Olivier’s father was a harsh and exacting disciplinarian — the type of Anglican clergyman father you usually only see in movies. He relied heavily on his mother, who passed away when Olivier was only 12. Her last words were supposedly “Darling Larry, no matter what your father says, be an actor. Be a great actor. For me.”

I’m somewhat dubious that a mother would utter a phrase so in line with the trajectory of Olivier’s star narrative, but bygones — Olivier fulfilled his mother’s wishes, and at 19 joined the Birmingham Repertory Company. He was put to work doing menial un-Olivier things: ringing bells, moving props, not playing King Lear, etc. But within a year, he had snagged the lead in (naturally) Hamlet and Macbeth. Stories like this emphasize Olivier’s “natural” and “in-born” genius — while he underwent a significant amount of training and long framed his own skill in terms of technique, from an early age, his star story was that of a wunderkind, a sort of acting genius.

Olivier’s first true break came in 1928, when, at the age of 20, he was cast as the lead in Journey’s End, the first play with a realist depiction of life in the trenches during World War I. Directed by and starring then-unknowns, Journey’s End would go on to great international success, and Olivier’s turn as the conflicted, self-loathing Captain Stanhope marked the beginning of his legitimate theater career.

In 1928, Olivier appeared with actress Jill Esmond in Bird With a Hand, but when Esmond was selected to go with the troupe to America, Olivier was not. So Olivier played the role of doting suitor, following Esmond across the Atlantic, proposing repeatedly, and finally wearing her down in 1930. Esmond opted for what can only be described as a massive pile of weeds for her bouquet at their very posh-looking wedding. (Is it posh? I don’t even know; all I know is that the groom is wearing a waistcoat, which seems very retrospectively posh indeed.)

While Olivier and Esmond would remain married for the next 10 years, the marriage was an unhappy one. According to Olivier’s own recounting, he failed to consummate the union on the wedding night, and came to blame his sexual repression on his uber-religious childhood. He decided to jettison his religion but keep his wife — smooth move, but it didn’t save the marriage, nor did the birth of their son, Simon Tarquin, in 1936. The religion-messed-me-up excuse might sound valid in hindsight, but bear in mind, most of this discourse originated with Olivier’s own autobiography — and as will become clear, he had some stake in excusing the demise of his first marriage.

Sexual complications were exacerbated by Olivier’s own mixed success. From 1930 to 1935, he became a major theater star, starring in Noël Coward’s Private Lives (“Coward” is shorthand for “big deal,” if you’re not a theater buff) and then, in 1935, Romeo and Juliet. As was common practice, he and another Shakespeare bigwig, John Gielgud, alternated the two most strenuous roles: one would play Romeo, the other would play Mercutio, and then they’d switch.

Now, I only really know Old John Gielgud, when he’s a mass of respectable wrinkles and bears a keen resemblance to Dumbledore (I mean that very respectfully). But take a look at Young John Gielgud:

Now pair that with 1930s Laurence Olivier:

I mean SERIOUSLY. The two were best frenemies, intermittently at war, critical of each other’s acting styles, and mad jealous whenever the other received better reviews. It was a rivalry that would structure the remainder of Olivier’s career, and the press loved the story of Britain’s Two Greatest Actors, in bitter love with one another.

For all his success on stage, Olivier was tortured by the cinema. It disgusted him — he thought it unconducive to skilled acting — but it also recognized it as the necessary means to international fame. He appeared in a smattering of films, mostly under contract to British producer Alexander Korda, but failed to make a mark. According to lore, Greta Garbo refused him as her co-star in Queen Christina — a slight that Olivier could not abide. [Sidenote: Garbo cast her on-again off-again love, John Gilbert, whose star was in decline. Over Laurence Olivier. And then trotted around in a bunch of velvet drag. I love her the most.]

Olivier went back to where he was appreciated: the Shakespearian stage. He joined the much-lauded Old Vic Company and, in 1937 alone, played Hamlet, Sir Toby in Twelfth Night, Henry V, Macbeth, and Iago in Othello. The list of his costars is filled with a preposterous amount of talent: Alec Guiness, Jessica Tandy, no fewer than a billion members of the Richardson/Redgrave family, and, of course, one Vivien Leigh.

Olivier had first seen Leigh onstage in The Mask of Virtue — a role for which she had won sudden and widespread acclaim. Leigh was lithe, luminescent, and flat-out gorgeous: the sort of gorgeous that makes people talk about her beauty before they talk about her performance.

Olivier complimented Leigh’s work, Leigh obviously swooned, but both were married and the relationship remained platonic. They even vacationed together, spouses in tow, on Capri — I’m envisioning lots of snappy bathing costumes and cocktails and burgeoning passions. The two were cast as lovers in Fire Over England, a British screen production set against the backdrop of Elizabethan England. Leigh plays an up-and-coming Lady-in-Waiting; Olivier plays a firey British soldier out to avenge his father’s death. It’s all very Historical Drama-rama, but would you look at the way they smoosh their faces together?

Whether the affair started before, during, or immediately after filming is a moot point — about as important as whether or not Brad and Angelina started making out before the end of Mr. and Mrs. Smith. What matters was that the chemistry between the two was palpable, and the British gossip columns went crazy. The Old Vic cast Leigh as Ophelia to Olivier’s Hamlet — Love! Betrayal! Drowning! So hot right now! — and the existing rumors gained strength. The inconvenient fact of Olivier’s infant son made the public opprobrium even more severe. Neither Olivier nor Leigh’s spouses would grant divorce, so Olivier and Leigh said screw it, we’re just gonna move in together. And while they didn’t pose for the papers as they moved into their new home, neither did they make it a grand secret.

Both Olivier and Leigh were secretly knackering for broader fame. Despite his continued love-hate relationship with the cinema, Olivier accepted the juicy role of Healthcliff in Samuel Goldwyn’s production of Wuthering Heights and traveled to Hollywood in 1938. The film’s director, William Wyler, had offered Leigh the (supporting) role of Isabella, but Leigh refused: naturally, she only wanted to play Cathy. But the role of Cathy was already promised to Merle Oberon — a major studio star who would “open” the film.

Oberon, a.k.a. Cathy, a.k.a. Queen of the Grand Forehead.

Olivier headed to Hollywood, leaving Leigh (temporarily) behind. This is the point in the story where I imagine Leigh engaging in some serious pouting and comparing-of-hairlines with portraits of Oberon.

If you’re not up on your Classic Hollywood history, here’s what you need to know about Olivier’s particular role in this particular film:

1) Samuel Goldwyn was one of the most successful independent producers of the studio era. His attachment = 99% guarantee of a monster hit.

2) Wuthering Heights was a massive pre-sold product, meaning everyone knew the story and would pretty much watch it no matter who was cast.

3) The film is a hunk-maker. Just ask The Fassbender.

In other words, unless Olivier really screwed things up — burnt off his eyebrows, grew a third nostril, fell in love with an inanimate object — he was bound for American stardom. With Olivier in Hollywood, Leigh saw her chance to enact a plot she’d been designing since she first read Gone With the Wind. The plan was simple: go to Hollywood; convince the film’s exacting producer, David O. Selznick, that a Brit could play the most famous Southern lady of all time; weather pissed off, vaguely xenophobic criticism from Americans; become giant movie star. “I’ve cast myself as Scarlett O’Hara,” she told a journalist. Olivier “won’t play Rhett Butler, but I shall play Scarlett O’Hara. Wait and see.”

Leigh pressured her agent, who worked under Myron Selznick, to get Selznick’s brother, David O., to consider her for the part of Scarlett. If things just got really confusing, let me simplify: Leigh worked the scene. Selznick agreed to screen her earlier work, but found her too British.

So Leigh came stateside, shacked up with Olivier, and they both barnstormed their ways through Hollywood. Olivier was pissing off Goldwyn with his traditional acting style (he reportedly called Oberon “an amateur”), while Leigh was pressuring Myron Selznick to make a face-to-face introduction to his brother so she could plead her case. They met, Myron said something clever like “Here’s your Scarlett, you big doofus” (approximation mine), Leigh read for David O. and director George Cukor, and suddenly Leigh was the dark horse in the race for the role of the decade. Cukor was all about her “incredible wildness,” and after some hemming and hawing, all very visible in the press, Leigh was cast as Scarlett.

Just imagine the media maelstrom: some out-of-country up-and-comer wins the most visible casting war in years, and she’s living, out-of-wedlock, with a man purported to be Hollywood’s Next Big Thing.

Gossip columnist Hedda Hopper led the charge of outrage: “Mr. Selznick was two years deciding on his Scarlett. And out of million of American women couldn’t find one to suit him. Which would seem a reflection on every girl born here.” TOUCHE, HEDDA. But a very effective way of engendering general disgust with a casting choice. Hopper published dozens of letters of protest: “Scarlett O’Hara is southern, old southern, with traditions and inborn instincts of the South. How in the name of common sense can an English actress possibly understand Scarlett, her times or the characterization is beyond a thinking American.” Or, a bit more bluntly: “No! A thousand times NO!”

As filming progressed, Cukor left the picture, prompting all form of incendiary rumors. The Los Angeles Times reported that the film risked a complete restart — or might never even be finished. The idea that Leigh had only come to Hollywood to “be near” Olivier gained traction: she didn’t even care about Scarlett! She’d follow him anywhere! The ENTIRE AMERICAN SOUTH, who apparently make all decisions as a collective, vowed never to see the abomination of an “All-British” production.

But Selznick labored to calm anxieties: Victor Fleming would take over as director; Leigh, like O’Hara, was of French-Irish descent; only one actor — Leslie Howard — was in fact British, as Leigh herself was born in India. And while Selznick was not a studio, per se, he did employ teams to manage his stars’ images, and helped keep Leigh and Olivier’s “be near-ness” as low key and inoffensive as possible.

He was helped, of course, by tremendous positive press — first for Olivier’s turn in Wuthering Heights, then for Leigh’s in Gone With the Wind. And a beloved film turn can change the conversation from one of scandal and disappointment to one of understanding and forgiveness. The normally moralizing Hopper was surprisingly supportive, especially after Olivier’s turn as Heathcliff made her feel something funny in her bathing suit parts. To wit:

Laurence Olivier’s part could have been garlanded with but, instead, Olivier was worth waiting for. And if I were only 20 years younger, I’d give that Vivien (Scarlett) Leigh a run for her money or die in the attempt. What a man! Not handsome; brooding eyes, square jaw, commanding voice. When Olivier says: ‘Come here, you’re mine’ how gladly you’d go. And even suffer a third-degree burn and love it when he put his hand on your arm.

As my Norwegian grandmother would say, OOFTA.

After seeing Gone With the Wind, Hopper even recanted her protest on Leigh’s casting. When Leigh returned to New York following its release, she

…won New York hands down. No airs or graces for that one. Just so happy to be back with Laurence Olivier and who can blame her? Wouldn’t we all like the chance? […] When you predict that she’ll be the sensation of 1940 you’re merely stating a fact. Mind, I was dead set against an English girl playing Scarlett, but she’s done such a superb job I’ve got to admit I was wrong and they were right. In fact, she didn’t play Scarlett; she is Scarlett.

Hedda’s new BFF Scarlett.

Olivier was nominated for Best Actor, and Leigh won Best Actress, but the two remained a moral liability. Despite their positive reception, the visibility of their living-in-sin-ness cautioned other American studios against signing them for another picture. Yet in January 1940, Leigh’s husband filed for divorce, and two weeks later Olivier’s wife did the same. With their divorces finalized, Leigh and Olivier wed in a miniscule ceremony, with only director Garson Kanin and Katharine Hepburn as witnesses. [CUE RYE HEPBURN QUOTE ABOUT MATRIMONY.]

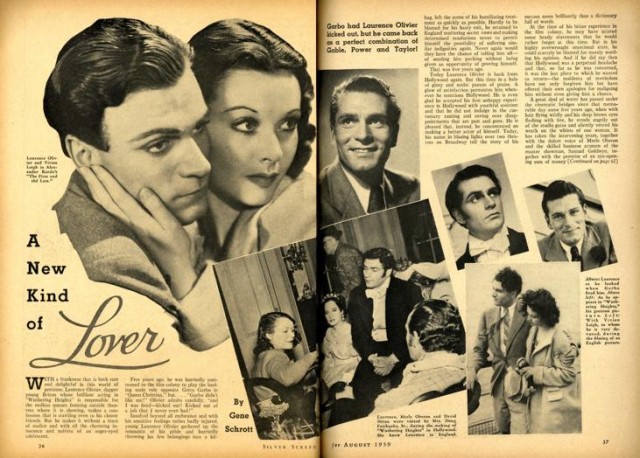

Until their marriage, however, the press dealt with the relationship as an open secret. A Silver Screen article from 1939, intended to promote Olivier’s turn in Wuthering Heights, declared him “A New Kind of Lover!”

We get the famous smoosh-face pose, but also another shot, in the bottom right hand, of Olivier with Leigh, “to whom he is very devoted.” The code was there for those who wished to read it, invisible for those who’d like to ignore it. The poster for 21 Days, a small British film released to exploit the pair’s American success, declared the couple “Excitingly together!”

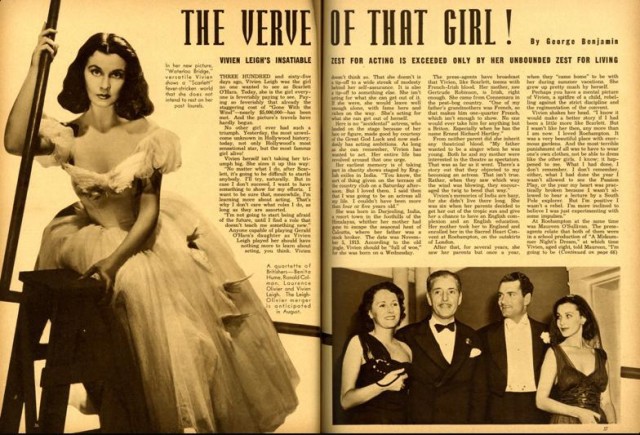

Olivier was not at Leigh’s side as she promoted Gone With the Wind, nor did she mention him in her acceptance speech for Best Actress. A Modern Screen cover story from June 1940 trumpeted “The Verve of That Girl!” and detailed Leigh’s high spirits, yet the only mention of her relationship with Olivier rests in the caption to a photo of the two, along with two other British stars, with the promise that a “merger” between the two stars was expected in August.

“Merger” sounds like what they’d call sex in Deep Space Nine, but bygones — their love seemed so real, so perfect, that both the press and their fans were willing to look the other way when it wasn’t precisely “legitimate.” This may seem like a trifle, but the way a public “feels” about a relationship does far more to normalize it than any piece of paper.

What’s more, Olivier was on a roll: after reifying his scorned-yet-sensitive image as Darcy in Pride and Prejudice, he appeared in Selznick’s next picture: Rebecca. Like Gone With the Wind, Rebecca was based on a ridiculously successful book — we’re talking Twilight levels of popularity. Originally, Selznick had promised Leigh the role, but she’d been lukewarm about it … until Olivier signed on, at which point she was totally into it. Selznick pulled a classic parenting move and effectively told her that if she didn’t want the part then, then she couldn’t have it now. In Leigh’s place, he cast Joan Fontaine — Olivia DeHavilland’s “ugly duckling” sister. [The details behind the casting of Fontaine are super juicy, but they’re to be savored another day.]

Rebecca gets a lot of flack as Hitchcock’s overly commercial, overly sentimental entryway into American cinema. But when Maxim yells “You thought I loved Rebecca? You thought that? I hated her!” IT’S THE BEST, IT’S SO SERIOUSLY THE BEST. Without spoiling anything big, it’s like that moment at the end of Persuasion when what’s-her-name gets the letter from what’s-his-name, and for a moment everything is awesome. Okay, okay, the moment in Rebecca is much more more sinister and gray-skyed thunderous, but you understand what I’m suggesting, which is that it’s a rom-com for those of us who secretly really only like the rom. Plus, if you look at me sideways, I might kind of look like Joan Fontaine, which makes me feel like I, too, can smoosh my face against Laurence Olivier’s.

The one-two-three punch of Heathcliff, Darcy, and Maxim de Winter was like a recipe for angry-sexbomb. I mean look at Maxim de Winter:

So moustachey, so tired-eyed, so stricken and ready for Joan Fontaine’s meek, wide-eyed love!

Both Pride and Prejudice and Rebecca were released in 1940 — the same year that a Leigh-and-Olivier production of Romeo and Juliet was bombing out of the New York stage. It would be their first true failure, and the two returned to Britain soon thereafter to assist in the war effort.

Years pass. Britain makes its way out of the war. Leigh appears in relatively little, and Olivier joins London’s New Theater, appearing in (and eventually directing) an astonishing list of productions between 1944 and 1949. At the same time, he directs and stars in a trilogy of films that forged his name into film history: Henry V (1944), Hamlet (1948), and Richard III (1955), featuring his old nemesis John Gielgud.

More than his Heathcliff, more than his Maxim, these are the roles for which Olivier is remembered. And despite Olivier’s reticence to direct, the film was a tremendous international success, earning nominations for Best Picture and Best Actor, plus a “Special Award for His Outstanding Achievement as Actor, Producer, and Director in Bringing Henry V to the Screen.” (Can I get a Special Award for Outstanding Achievement in Showering Before 5 p.m.”?) It marked the first truly successful filmic Shakespeare adaptation, and made it clear the Bard and Hollywood could mix. In other words, every time you ogle Cher’s closet in Clueless or marvel at Julia Stiles’ table dancing in 10 Things I Hate About You, pour out an inch of your white wine for Olivier.

Or just pour out your wine for Olivier’s slinky tights leg.

Yet throughout this period of tremendous success and acclaim, Leigh endured various forms of suffering. After she and Olivier returned to England, they helped the war effort in various ways: films like Hamlet were viewed as “public moral boosters” (WHAT!?) and both stars toured and performed for the troops. On one of these tours in Africa, Leigh fell ill with what later be diagnosed as tuberculosis and took months to recover. Soon thereafter, she discovered she was pregnant, but miscarried within weeks. These events precipitated a deep, stultifying depression, and the first of many breakdowns that would later be diagnosed as bipolar disorder. For us, the symptoms are familiar: excitement and frenzied engagement over several days, followed by devastating declines, outbursts, and remorse.

In 1947, the couple went on a tour through Australia and New Zealand to raise funds and promote the Old Vic Theater, of which Olivier had been appointed head. Leigh repeatedly refused to go on stage, and cast and crew observed tumultuous fights that occasionally escalated to slapping. It was the beginning of the end — years later, Olivier would claim that he “lost” Leigh in Australia.

But Leigh still had more to give: she was cast as Blanche DuBois in the British staging of A Streetcar Named Desire — a role (and play) that generated a firestorm of controversy and praise. In typical fashion, Leigh and Olivier pooh-poohed the play’s commercial success, suspecting that most audience members were there for pure titillation. No matter: Leigh agreed to star in the Hollywood adaptation featuring Marlon Brando, who had steamed up the American production.

Leigh modeling the only appropriate expression for Streetcar-era Brando.

After nine months of filming, the results were scintillating. If you’ve seen, then you know. Leigh would go on to win her second Academy Award for Best Actress, but the film had, in her words, “tipped [her] over into madness.”

What followed was a series of declines and recoveries, happiness and despair, and numerous affairs on the part of Olivier, all punctuated by a final pregnancy and miscarriage. Even as they were driven apart, they continued to appear in dozens of productions, and both received tremendous reviews during this period. By 1958, the marriage was effectively over, with Olivier enmeshed with then-co-star Joan Plowright. Leigh began her own open affair with actor Jack Merivale, who assured Olivier that he would care for her.

In 1960, Olivier finalized the divorce and married Plowright, with whom he’d father three children. There was Spartacus, more Shakespeare, a pairing with Marilyn Monroe (which inspired last year’s I Love Eddie Redmayne’s Freckles errrrr My Week with Marilyn), a celebrated yet controversial portrayal of The Moor in Othello, a smattering of Academy Award nominations. Leigh would live with Merivale for the rest of her life, periodically returning to the stage to prove that even without Olivier her work was praiseworthy. Yet in July 1967, Leigh succumbed to a recurrence of tuberculosis, and died, late at night, alone in her bed. Olivier, himself in treatment for cancer, rushed to her side, reportedly “filled with anguish.”

Olivier spent his last 30 years as a workaholic, reproducing the same rigorous performance schedule that had characterized his rise to fame. He worked so intensely, and for so long, that many interpreted it as a means of making penance for his behavior toward Leigh. Still, there are dozens of plays, movies, roles, and dalliances this piece hasn’t even touched. I could spend another 4,500 words of your time simply describing his 1960s career, the influence of his filmic Shakespeare, or the dozens of accounts, some more substantial than others, that he was bisexual. But for all of his genius, all of his work in sustaining and rejuvenating the theater before, during, and after World War II, his passion for Leigh — and hers in return — remains his defining feature.

The more I read, the more of his films I see, the more pictures I see of Leigh and Olivier together, the more complex the situation becomes. As easy it would be to paint Olivier as the cad who left, the man of great passion and great unkindness that I introduced in the beginning, it seems clear that no one, save Leigh and Olivier, the lead players in the production of their own lives, will know precisely what happened between them, and what finally drove them apart. Bipolar disorder — and psychiatric disorders in general — were still so little understood in the 1940s and ’50s that it’s difficult to place blame on Leigh or Olivier for their relationship’s demise. Leigh was ill, and illness left untreated, no matter what part of the body or soul it afflicts, can and will drive people apart.

So many great works of the stage focus on great passions and great injustices, recounting how tremendous misfortune strikes those who do or do not deserve it. How we react to misfortune — bravely, shamefully, brokenly — is the stuff of character, the very meat of performance. However heartbreaking, it seems only fitting that Olivier’s life, with Leigh beside him, turned, without his control or consent, into tragic theater for the world to observe.

Previously: Katharine Hepburn’s Trousers.

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.