Not Chasing Amy

by Jason Good

We were nestled in the relationship sweet spot: lying on separate sofas watching Gwyneth Paltrow deliver her Oscar acceptance speech for Shakespeare in Love. Then Amy muted the television and cleared her throat. The words came off her tongue too cleanly to be natural, making me suspect that her cats had heard them a few times before I did.

“What we have here might be as good as it gets, but I need to find out if things can be better with someone else. I’m going to move out, but not for a month because I need to save money. I’m going to stay here until then.”

It was a demand so concise and stripped of setup that I accepted, slack-jawed, as if a brawny repo man had shown up to take my car.

Before Best Director was awarded, I’d acquiesced to the details. We would continue to share our one-bedroom apartment, as well as its only bed — but I wasn’t permitted to be in love with her anymore.

We’d met at a party in Austin. Amy was friendly and eager to connect, but I could tell immediately that she was troubled. Her laughs ended abruptly, as though joy had to be carefully balanced with melancholy. But whatever her demons were, they had nurtured a dark sardonic wit that made any emotional lability seem worth the ride.

Over the next few nights after the Oscars, my requests to spoon were denied with disgusted refusals: an emotional switch had been toggled. I couldn’t help but think there must be something more important fueling her detachment than the trite prospect of a better life with “someone else.”

Amy was routinely gone in the morning before I woke up, and she didn’t return until late at night. When I discovered the password to her email was no longer “p0etry,” I changed mine to “bitch1971.” In my defense, it was the year of her birth, and I was desperate to heal.

I was also out of work. And as the days passed, eventually discovered that festering alone at home devouring pornography and bean burritos wasn’t helping my self-esteem. I started spending my afternoons and evenings at a local bar. I think it was a hipster place, but 20 somethings in ironic hats weren’t called that yet.

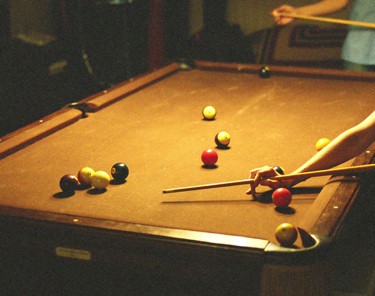

I made friends with the owner, Gretchen, who also bartended in the early evening. She wore vintage ’50s cardigan sweaters, had short dark hair styled with bobby pins, and loved the Pixies. We played Jenga on the bar, shared cigarettes, and when business was slow played pool.

As a stranger to my situation, Gretchen offered a perspective that rattled my already weak sense of masculinity. She was appalled that I’d agreed to let Amy stay in our apartment, and more than a little leery, if not disgusted, when I told her we still shared a bed. She wanted me to stand up for myself. As I continued, nightly, to seek solace and strength from my sexy new bartender friend, my life seemed to be following the lyrics of a Billy Joel song I couldn’t quite remember.

Each night, I returned to our apartment a little more capable of pretending I was building a new life for myself. Sometimes, I would even attempt playful conversation, but my boozy optimism only annoyed Amy.

One morning she went to work, forgetting her purse in the apartment. I’d decided the night before to repair my favorite shirt, which I’d ripped on the banister during a drunken jaunt up the stairwell. Not having a sewing kit, I fished through Amy’s bag for a safety pin and left it in disarray.

That night, I received an angry call from Amy. “Stay out of my damn purse!” And she hung up.

Two weeks earlier, I had been free to help myself to safety pins, keys, Chapstick, gum with hair on it, and coins stuck to wet cough drops. Now, just because she’d decided to attempt a lifegasm, her bag was suddenly sacred space. Had that much really changed?

When her move-out date arrived, she threw all her clothes in a suitcase, leaving me with her valuables: camera, cassette tapes, and two cats. It seemed more like she was taking a vacation than leaving a life.

Months passed, and, as a result of my penchant for $5 pints, I could no longer afford the apartment. I accepted an offer from friends to take temporary shelter in their spare bedroom. These were the obligatory couple-friends with whom Amy and I used to lie about our sex life and play euchre. I brought Amy’s orphaned belongings with me and crammed them into my new room. The cats were unhappy and peed on the paper grocery bags I was using as makeshift luggage. I had no money and no plans, but I spent as many evenings as I could at Gretchen’s bar, even though I had to take a bus to get there.

I tried talking to my new housemates about Amy, but they were oddly reticent. We had all been great friends, so I understood their unwillingness to trash her, but how could they not agree I was owed some sympathy?

After a month, I’d overstayed my welcome and started planning a move to New York City. I just needed to find a home for Amy’s cats. I asked my friends how to reach her so perhaps she and I could agree upon their fate.

My friend took a deep breath, silently poured us each three fingers of expensive Scotch, and gestured to a chair. He sounded disappointed and looked guilty.

“Amy said she was going to tell you, but I guess she’s not. We promised her we wouldn’t say anything until she had a chance, but we’ve both decided it’s been too long, and you deserve to know the truth.”

As he continued to speak, Amy’s behavior over the previous three months started to make sense.

A few weeks before the Oscars, Amy and I had each gone on short trips to our hometowns to visit friends. While back in San Diego, Amy had rekindled with an old high-school flame. I’m assuming they’d had sex outside under the stars at a golf course, then spent the night there, teaching each other the different constellations and sharing thoughts on mortality. During a moment of post-coital weakness, he probably had even agreed with her that God must be a woman.

Whatever the details, the reality is that they became sweet enough on each other that he proposed. And she accepted.

Amy had returned to Austin engaged. She’d lived with me, slept in our bed and watched most of the Oscars with me, all while secretly “soul-mated” with someone else. She hadn’t so much stopped loving me as she’d simply transferred her feelings to another man, like moving a cellphone number to a different carrier.

My friend told me that she wore her engagement ring around town, showed it off to our friends, and then hid it in her purse before returning home. That explained the angry phone call; while searching her purse for a safety pin, I might have discovered the empty ring box and exposed her secret. Why she didn’t hide it better, I don’t know, but perhaps, deep down, she thought that getting caught might be simpler than being honest. And who can blame her.

She’d left our apartment on a muggy morning to embark on a new life; her fiancé of one month was waiting in a taxi around the block. They’d driven to the airport, hopped a flight to Las Vegas, and wed that evening.

After hearing the story, I spent the next week walking the streets of Austin feeling like I‘d stumbled onto a movie set where everyone was acting except me.

Word spread among friends that I was in on the secret. I wanted them to validate my anger, but I understood that doing so would indicate that they viewed Amy’s actions as unfair and evil instead of predictably impetuous and worrisome. In their minds, and eventually mine, I hadn’t been dumped; I’d been released to find a partner who wasn’t destined to run away.

During a recent move from an apartment in Brooklyn to a house in suburban New Jersey, I came across Amy’s camera and cassettes. They felt significant in the way a rosary might feel to a reformed Catholic. I found some comfort in them, as they represented a need for drama that I’d outgrown. Crazy people are exciting, but most will unwittingly steer themselves toward a life of entropy instead comfort.

Sometimes even the most awkward rebounds result in graceful put-backs. I’m five years sober now, and married to Gretchen. In fact, it was she who encouraged me to quit my job to be a writer. We have two small boys who love that I’m home all day, and while my life is chaotic and often maddening, it’s also filled with warmth and security: the good kind of crazy.

The cats now live in Portugal. Gwyneth Paltrow is a country singer. And Amy, I recently heard, is on her third marriage and finally settled.

Jason Good is a comedian, writer, and numerous other things he’s not willing to admit publicly. A children’s book based on his blog post, “3 Minutes Inside the Head of My 2 Year Old” is due to be released in 2013. He is also a contributing writer to Parents Magazine. Jason lives in New Jersey with his wife and two sons, and enjoys making them laugh more than anyone. You can follow him on twitter @jasonmgood.