The First Sandra Lee: Poppy Cannon and Her Can-Opener Cuisine

by Emily Matchar

“At one time a badge of shame, hallmark of the lazy lady and the careless wife, today the can opener is fast becoming a magic wand, especially in the hands of those brave, young women, nine million of them (give or take a few thousand here and there), who are engaged in frying as well as bringing home the bacon.”

— Poppy Cannon, The Can-Opener Cookbook (1951)

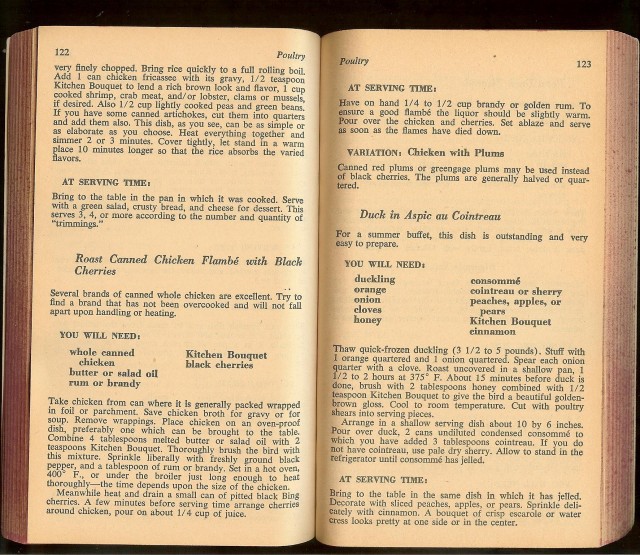

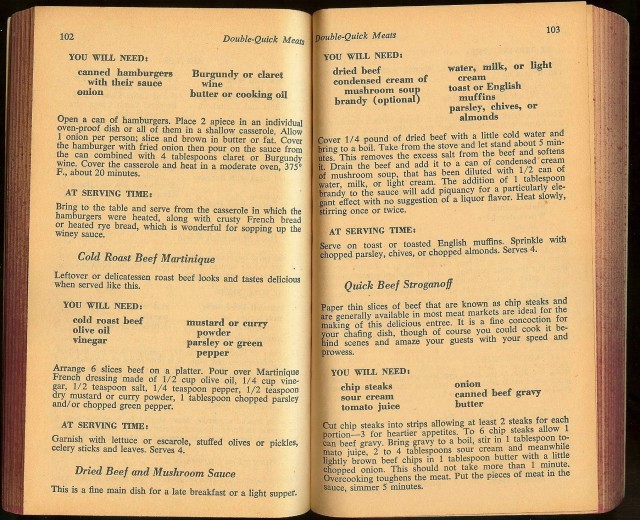

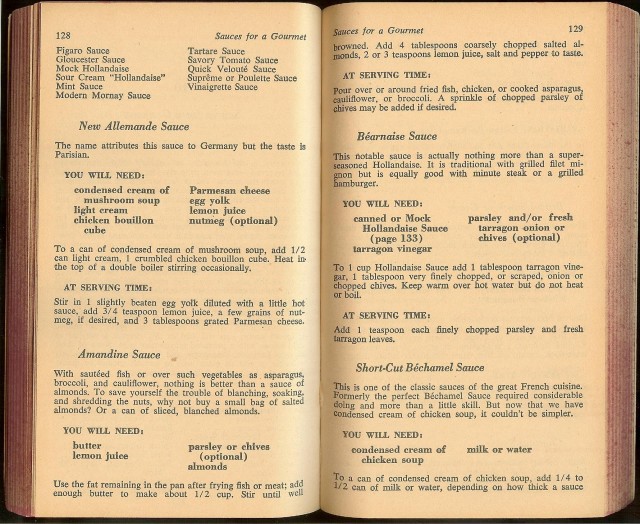

Fifty years before Semi-Homemade star Sandra Lee began earning foodie sneers with her grotesque, corn nut-studded Kwanzaa cake and tragic tomato soup lasagna, there was another food celebrity the cultured classes loved to hate: Poppy Cannon. A mid-century food editor and cookbook author, Cannon was best known for her now-infamous Can-Opener Cookbook, published in 1951 and full of recipes whose baroque names belied their lowbrow ingredients — “Frizzled Ham with Bananas Haitian” (canned ham, bananas, rum, butter), “Lucanian Eggs Au Gratin” (eggs, canned macaroni and cheese).

She was an unabashed believer in the magic of convenience food to create quick, glamorous meals with no fuss: cream of celery soup, canned shrimp, Vienna sausages, frozen chicken. In her brilliant history of 1950s food culture, Something from the Oven, writer Laura Shapiro describes Cannon’s style thusly: “She advised readers to ‘mix furiously’ or ‘stir like crazy’ or ‘fling’ ingredients together; once she referred to tossing a salad as ‘salad-flinging.’ These mannerisms scattered through her paragraphs evoked a kind of screwball comedy set in the kitchen, with the cook as the madcap heroine.”

Like Lee, a self-made millionaire, philanthropist, and the live-in companion of New York governor Andrew Cuomo, Cannon’s life outside the kitchen was far more fascinating than her dismal recipes might have suggested. She cut a prominent figure in her era, hobnobbing with everyone from Eleanor Roosevelt to Lena Horne to Alice B. Toklas, appearing on TV with Edward R Murrow, and entertaining diplomats in her living room. She was tall and zany and owned it — she adorned her six-foot frame with giant, eccentric turbans and swished around glamorous New York parties like a duchess. Her affair, and subsequent marriage, to NAACP secretary Walter White was a great public scandal in an era when interracial marriage was illegal in nearly half the country; Cannon simply sniffed at naysayers and published a cookbook dotted with florid love poems to her husband.

And just as Sandra earns major snark from food writers and celebrity chefs — Anthony Bourdain memorably called her the “frightening Hell Spawn of Kathie Lee and Betty Crocker” — Cannon also got plenty of flack from the tastemakers of her day. Fellow editors laughed at dishes like asparagus-Spam-macaroni casserole. James Beard thought she was a joke.

Did she give a damn? No she did not. She had bigger (canned) fish to fry.

Canned chicken? Seriously?!

It wasn’t that Poppy Cannon had no taste buds. It wasn’t that she didn’t know good food. Quite the opposite. Born in South Africa to Lithuanian Jewish parents and raised in Pennsylvania, she won a scholarship to Vassar, became a writer and editor for women’s glossies like Mademoiselle and Ladies’ Home Journal, and traveled in refined circles — her third husband was a Waldorf-Astoria executive who gave her privileged access the finest in haute cuisine.

But Poppy Cannon believed in convenience food. She thought that career women — described as “business girls” by the reviewers on her book jacket flaps — deserved to come home and enjoy fabulous dinners in minutes, just like men! In Cannon’s mind, women had better things to do than spend all afternoon fussing over duck a l’orange or baking cherry pies. “The heroines of her column were constantly inviting men to brunch or throwing together a spontaneous after-theater supper or staging a wedding breakfast for ten in a one-room apartment — even though they were working girls and had never cooked in their lives,” Shapiro writes.

Cannon’s The Can-Opener Cookbook was a testament to her faith in the idea that, with a little help from the “magic wand” (a.k.a. can-opener), women could mix work, domesticity, and fabulous social lives. Long day at the office? Try feeding your family a store-bought angel food cake “glamorized” with ice cream and coconut flakes. Business associates dropping by for a last-minute dinner? Simply mix eggs and canned mushrooms, splash the whole thing with a glug of rum, put a match to it, and “appear on the scene bearing this delicate omelet wrapped in fragrant flames.”

Disgusting? Probably. Okay, almost certainly. But food is never just about taste. It’s also about culture and desire and the ways we want to present ourselves to the world. Poppy Cannon wanted convenience food to be a miracle for working women. So she held her nose and believed.

See, Cannon understood working women. At a time when women were expected and encouraged to be financially dependant on their husbands, Cannon was viscerally familiar with the downside of such arrangements. Her father walked out on her family when she was a teenager, leaving her and her siblings alone with their mentally ill mother. She herself was married four times and divorced three, and had three children by three different men. Her food writing work wasn’t just a lark — it was a necessity.

Sandra Lee came from similar hardscrabble beginnings. Raised in California and Washington by a drug-addicted and physically abusive mother, she raked neighbors’ leaves for extra grocery money on months when the food stamps didn’t stretch far enough. Later, she went to live with her estranged father, who was soon sent to prison for rape. Like Cannon, she was hell-bent on escaping her roots. By her late 20s, she’d become a millionaire selling a line of DIY curtain hardware; she used her money to launch her Semi-Homemade empire in her 30s. Like Poppy Cannon (nee Lillian Gruskin), she completed her transformation with a name change: Sandy Waldroop became Sandra Lee.

Feminism and convenience food have an uncomfortable shared history. Here’s one story: housewives, brainwashed by Betty Friedan and Co. into thinking they were “unfulfilled,” served as willing dupes for an evil empire of Industrial Food, happily trashing generations-long culinary traditions in favor of quickie Rice-A-Roni dinners before dashing off to consciousness-raising groups. Families suffered, kids got fat, grandma’s special brisket recipe was lost forever. Now we’re sorry.

Here’s another story, closer to the (complicated) truth: food companies, having developed all kinds of new canning and freezing methods while provisioning the troops during World War II, were keen to find a way to sell their new products to the domestic market after the war ended. Homemakers were suspicious at first (some early products, like powdered wine and freeze-dried cheese, never took off — imagine that!), but the companies persisted through clever marketing, convincing women that convenience foods were tasty and fun and easy and modern. By the mid-1950s, long before Betty Friedan showed up at the party, the average middle-class woman was studding her chicken salad with marshmallows and serving ham n’ canned pineapple spears at backyard luaus. Though food companies — and writers like Poppy Cannon — envisioned convenience foods as a boon for “business girls,” it was in fact stay-at-home housewives who took most advantage of these new foodstuffs. Even today, working women and stay-at-home moms use convenience foods in about equal numbers.

The difference between Cannon’s era and Lee’s, though, is profound. While a midcentury homemaker probably gave little thought to the cultural symbolism of her canned peas, today’s middle-class home cooks are dealing with a very different — and much more fraught — food culture.

More than 60 years after The Can-Opener Cookbook was published, Americans are busier than ever. Families today are far more likely to be headed by two working parents or one single working parent than they were in the 1950s, and parents who work are working longer hours than they were at midcentury.

The Amazon.com reviews for Sandra Lee’s Semi-Homemade series of cookbooks reads like a group therapy session on the difficulties of 21st century work-life balance:

“I am a single mom with two kids to feed and a boss that thinks I should work 50 hours a week just like the guys. This book lets me feed my family hot delicious meals no matter how late we get home or how much we have to do.”

“I’m a guy. I work. And every other week two kids descend on my house fridge like hungry locusts. I may not enjoy cooking but it is necessary evil… [the Semi-Homemade recipes] go step-by-step and are written for layman… My kids get hot food, they actually eat it (more times than not), and I feel like a good parent.”

“In a perfect world, I would cook wonderful home-cooked meals every night. In a perfect world, I would only use fresh ingredients… In the real world of two hard-working parents, demanding children and constant time pressures, this book is a lifesaver.”

“To me, the joy of cooking is having time to enjoy a meal with my family and then using the time I saved to help my kids with their homework… If that makes my lifestyle “sad,” so be it. I’m a single working mom, not a food writer.”

It’s no surprise that some of these reviews sound kinda defensive. In the years since The Can-Opener Cookbook was published, we’ve become ever more discriminating about what constitutes “good” food, both from a health and a taste standpoint. One of the downsides of this growing food consciousness is a certain kind of judgmental attitude towards people who cook and eat “wrong.”

When Virginia Heffernan, a New York Times columnist, wrote a cheeky ode to Poppy Cannon, explaining that she herself loves to use healthy “hacks” like frozen broccoli and cut-up cheese cubes to feed her kids, Times commenters exploded in wrathful judgment:

“’Lazy’ is the first word that comes to mind on reading this. Lazy of mind and of body. It would be even easier if someone else opened the can of peas for you, right?”

Shortcut-promoting chefs like Sandra Lee may be popular, but they’re subject to an awful lot of overheated, suspiciously classist-seeming hatred — Lee has several hate websites devoted to deconstructing what anti-fans see as her tacky makeup, her tasteless “tablescapes,” and her other supposedly déclassé qualities. Hating her recipes seems fair enough — they’re often pretty grotesque-looking and of dubious nutritional value (uh, hello “Paradise Crab Dip Wontons”: canned crab, cream cheese, steak sauce). But many of Lee’s most high-profile detractors seem to focus their wrath on the very concept of “convenience.” In an essay railing against the idea of “quick and easy meals,” respected food writer Michael Ruhlman wrote the following:

Maybe you don’t like to cook, maybe you’re too lazy to cook, maybe you’d rather watch television or garden, I don’t know and I don’t care, but don’t tell me you’re too busy to cook… I know for a fact [emphasis mine] that spending at least a few days a week preparing food with other people around, enjoying it together, is one of the best possible things in life to do, period. It’s part of what makes us human. [Emphasis mine.]

Lee and Cannon’s food may be atrocious — no one could defend Sandra Lee’s “Sensuous Chocolate Truffles” (canned chocolate frosting mixed with powdered sugar) or Poppy Cannon’s “Quick Lobster Newberg” (canned lobster, condensed cream of mushroom soup, egg, sherry). But unlike Ruhlman, both Sandra Lee and Poppy Cannon understood that some full-blooded human beings actually find cooking a giant pain in the ass. And they also understood that when people said they were too busy to cook, they probably meant it.

Emily Matchar is the author of an upcoming book about women and domesticity in the 21st century (Free Press, 2013). Check out more of her musings at her blog, New Domesticity.