IUDs, or A Detailed Guide to Long-Term Sperm Scarecrows

by Lola Pellegrino

To nobody’s surprise, your Health Secretary received more curious inquiries about IUDs than any other topic. I hear you: an encounter with something that seems perfect for your vaginal needs, but what’s this nasty reputation. You ask yourself, “Is the bad stuff I’ve heard true? Could we work together — even in the long term?” If we’re still talking about IUDs, and I’m not sure we are, there are good answers to your questions. Let’s “I” and “U” “D”-scuss.

What is this thing?

The IUD is a T-shaped plastic or copper device that hangs out in your uterus as the most effective sperm scarecrow money can buy. It doesn’t protect against STIs. The two kinds available in the US are the Mirena and the ParaGard, and they both fit in my mouth.

Both provide extremely effective, immediately reversible birth control that is ready to go when you are and can’t be forgotten. Mirena is 0.3% more effective than female sterilization, even. Both can be left in for many years. The continuation rates are the highest for any reversible birth control, besides the implant. Unfortunately, you can only have one at a time. How to choose a favorite!?

Here’s a very comprehensive handout, but start with the biggest difference between the two: Mirena makes your periods lighter and ParaGard makes them heavier. By one year of Mirena, the progestin-containing hormonal one, average blood loss has decreased 90%, and 20% have no period at all. By 5 years, 60% don’t. There’s an initial period of increased pain and irregular bleeding — an average first month has more days with spotting/bleeding than without — but the amount of blood loss is already decreasing. If you’re the kind of person who couldn’t handle a lot of spotting, would get freaked out by not having a period, or abhors change, Mirena might be tough, especially at first. You might want a ParaGard, which doesn’t affect how regular your cycle is; however, it does on average increase the heaviness of your period and the days you’ll bleed for. If you already have a heavy/painful period, or you don’t think you could tough one out, it’s probably not for you. Fortunately, Teva, the manufacturer of ParaGard, does make other forms of highly effective non-hormonal birth control.

The other big diff is that Mirena has hormones and ParaGard doesn’t. You probably have some feelings about hormonal birth control, one way or another. There is progestin (Levonorgestrel) in Mirena, but not estrogen — if you’ve been told you shouldn’t take birth control pills, the estrogen is most likely the reason why. The amount of Levonorgestrel released is equivalent to about 1 mini-pill a week and goes direct delivery to your endometrial lining. This changes the type of side effects that occur. Local side effects, like bleeding changes, are much more common than system-wide side effects. Those side effects — headache, breast pain, acne — do still happen, but they happen less frequently and to a much smaller percentage of users (compared to users of the pill or the Depo shot, for instance, both of which have progesterone in them).

Bleeding and other side effects with either IUD are most significant in the first 3 months, but the main reason why people stop using their IUDs is frustration with the changes: bleeding too heavy/painful with ParaGard or bleeding too irregular or no period at all with Mirena. There’s most likely a way to make your bleeding better for you, so don’t tough it out! In addition to the “tincture of time,” reproductive health godbody Dr. Robert Hatcher suggests considering a few rounds of the pill. (By the way, he looks like this and literally all of his answers are this charming.) If it’s a pain issue, more likely with ParaGard, NSAIDs like Ibuprofen or Naproxen can really help, especially if you take them on a continuous schedule from the day before/of your period.

Cool, Can I Get One?

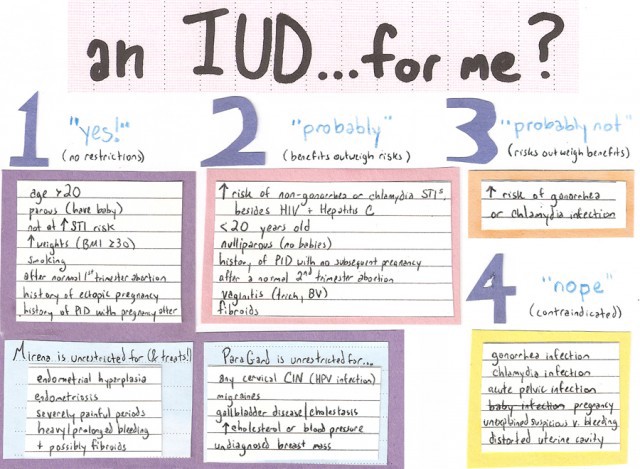

Most important question: do you have 6 centimeters of empty uterus? Whether or not you’ve had a kid before, you probably do: the percentage of nulliparous (no-baby-having) women age 15–25 without a uterus that size is only 30%. Next, let’s look at the WHO’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraception, which provide clinical guidelines for selecting the safest contraceptive method based on risks of every imaginable type of medical issue. Risk of use is rated on a scale of 1 (no restriction) to 4 (no way). The IUD has very few hard “no”s. For you, an INFOGRAPHIC.

(Click here for a larger version.)

The average healthy 26-year-old in a long-term relationship who’s never had kids but did have one normal first-trimester abortion (“Lola”) scores a whopping risk rating of 2: benefits outweigh risks, method recommended for use. Here are general risk factors for chlamydia/gonorrhea, but you should make an individual assessment with your provider. The construction paper may have already given it away, but the above is not very comprehensive. I recommend the brave/curious peruse this summary or the full guidelines.

So, looks like IUDs are a safe option for most women! So why did you hear … anything other than that? The origination of the IUD’s bad rep in America was when one of the O.G. IUDs called the Dalkon Shield caused infertility and sepsis in great numbers with its horrible, Facehugger-from-Alien “clawlike appendages.” There have been great articles recently covering the historical and scientific aspects of what happened next, but the sum total is that fear, misinformation, and underutilization have been perpetuating each other ever since.

Depending on what graph comparing IUD use by country you’re looking at, our rate of 5.5% is either “very low” or “dead last,” even though the usage rate almost doubled between 2002 and 2008. This is to say: if you want an IUD, you might still have to safari into medical self-advocacy. A common species you’ll find there is a well-meaning clinician who thinks they’re preventing you from harm: you can tell them by their suggestion that you first try another “less drastic” method, like the pill. They’re most likely just under-informed, so you can go so far as to furnish research like ACOG’s recommendation that IUDs be offered to most women as first-line contraception. Or share this thought experiment!

“You’re sick and there’s two treatments: a device that sets up in minutes and works for years and a pill that’s only as effective as the device if you take at same time every day forever, which is actually so difficult that 31% of users fail at in the first 6 months. Wouldn’t you be like, ‘Fucking give me the easy thing!’ (put on sunglasses) So why is preventing pregnancy so different that you wouldn’t treat with the most effective, least likely to fail treatment first?” (drive away in red convertible)

Every provider has a different risk tolerance. It’s possible that the reason they don’t want to insert a Mirena is because they’ve never done it for someone without kids before. If someone says they won’t insert an IUD for you, they should able to tell you where they’re coming from and give you suggestions about other options to consider. But also be on the lookout for clinicians who make their recommendations against scientific evidence to rationalize their own moral beliefs. You’ll know this species when any questioning about why the IUD can’t happen for you is dismissed with a moral judgment, like “you have too much sex” or “because you’re not married.” Say thank you, disarm them with one of those hoods you put on birds to make them sleep, and switch to someone else in their practice. Or another practice entirely!

Fun-ding

I tried. IUDs are paid for up front: what you pay = the price of the device + the price of the medical care. CostHelper says $10-$160 with insurance and $210–800 without. It is the cheapest option in the long term, but the ability to think about cost in the long term is out of reach for most people. More succinctly, fuck-all it gives you if you don’t have that kind of money up front, and many people don’t, including myself. Shout out Republican Congresspeople, current sponsors of this paragraph and a fucked-up world where people must financially justify if they can control their own bodies! Thinking of You each time I have a conversation with a patient unable to afford contraception: “Let’s work this out — what’s not being forced to become a mother worth to you? Up front? Monthly?”

Strategies! Insurance: call the number on your membership card and ask if you’re covered for CPT-58300 (IUD insertion) and CPT-58301 (IUD removal). Then, ask if you’re covered for the actual Mirena (CPT J7302) or ParaGard (CPT J7300) device. If they say no, ask if the device is covered under your pharmacy benefits or if you can use a flexible spending plan.

No device coverage or no insurance: people whose income qualifies can get the Mirena for free through the ARCH Foundation and the ParaGard through PPAP. There are also payment plans available from the manufacturer. Mirena’s has 3 payment options, with the lowest payment $35 month/2 years, and ParaGard’s payment plan is $40 month/1 year. To try to save money on the visit cost, check out your local Planned Parenthood or public health clinic: many of these have in-house programs that subsidize IUDs.

How Go Insertion?

All this chatter and the damn thing takes like 5 minutes to put in. Okay! First, we make sure you’re not pregnant. Since there’s some lead time before a pregnancy test turns positive, you’ll probably be asked to ensure you’re not pregnant by not having sex for 2–3 weeks before the test or by being on a reliable birth control method. You might also get STI tested, and your uterus will be measured for sufficient size and shape. This is done in different ways: ultrasound imaging, a pelvic exam, or by inserting a “uterine sound” — thin rod with a ruler on it — through the cervical os (cervix = donut, os = donut hole).

You may have noted that pain during insertion seems to differ wildly, especially for internet commenters. Some people sense nothing but a butterfly wing’s momentary twinge while others discover an extended sensation indistinguishable in severity from being on fire. Good news: a large analysis of multiple studies of insertion-pain intervention found that no method works better than another. Bad news: uh, that’s because none of them worked. Until the evidence comes through, go with your gut and what your provider suggests. A hot water bottle is a good look afterward.

Who feels more pain? Oh, who knows, Edith found me at a bar! Jokes, we met in yoga class. Double jokes! Edith isn’t real. You’re more likely to feel pain at insertion if you’re nulliparous. Even then, it’s not that bad: in a study of only nulliparous patients, 9% had no pain, 72% had moderate, and 17% had severe. 72% reported they found the insertion “easy.” Other factors found to predict more pain were painful periods, higher level of education, and longer time since last pregnancy. Oh, and you’ll have more pain if you think you’re going to have more pain: “[Anticipated pain] was slightly higher than overall perceived pain … Studies of other gynecologic procedures also show anticipated pain scores to exceed actual scores.” What this says is: if you can relax, that will help. And if you can’t, it’s okay, because it’s still not going to be as bad as you thought it would be.

Another evidence-free zone is when in your cycle you should schedule your insertion: we know it’s definitely not necessary to be on your period, and there’s conflicting studies as to whether it’s even helpful to be. The latest recommendation is to be mid-cycle, but that might change. One thing that might happen is that if your cervix proves difficult to maneuver, coming back during Shark Week is one of the methods they may try, along with softening your cervix with misoprostol.

IUD insertion is mostly similar to what you’ve already done for your annuals. You’re put in the stirrups and a speculum is inserted. Sometimes, the cervix is cleaned by a q-tip. The path for the IUD is straightened out by holding your cervix with a pair of lady-tongs called tenaculum, which you should never google pictures of because they look way worse than they actually are, I swear to you. The os is dilated if needed. The IUD itself comes in a long straw that functions as a tiny intrauterine cannon, as seen with the ParaGard below:

Please don’t be alarmed if your gynecologist has less-whimsical helpers! We thread the straw into the uterus through the cervical os, withdraw the tube, and bam. You’re done. Your provider might cut the strings or leave them as-is: whichever happens, ask how long they are so you have a baseline for when you check them yourself.

Because of the 1% risk of a vasovagal response, your provider might have you lie down for a while before you leave, even if you feel fine. The same nerve that regulates your heartbeat runs through your cervix, so putting something through the cervix can accidentally trigger the nerve. If this reaction does happen, your blood pressure/heart rate will drop, causing a brief spell of symptoms like fainting, dizziness, nausea, and clamminess. To summarize, while a vasovagal response is one of the scariest harmless things that can happen to a human, it is also the most tangibly scientific evidence of the heart/vagina connection we have today. I thank you.

Now You’ve Done It

I recommend spending the time between insertion and resuming sexual activity contemplating being one step closer to a cyborg and perusing this excellent patient education from Bedsider. You’ll see there’s very little you need to do to take care of an IUD over time. As long as it’s in there, your IUD is going to be TCB. The most you’ll probably think about it is in responding to those around you who are horrified by your decision. “The complications!” they’ll say. If you hear something and it’s not here or in any patient education you received, perhaps it can be found exhaustive document on IUD myths. Here’s the gist:

1. Perforation: 1 out of every 770–1600 insertions. This sounds scary as hell, i.e., but it’s rarely dangerous. The uterus will most likely heal itself: think about how often and well people heal their entire uterus being cut open for a C-section. There is conflicting evidence that perforation can happen at any time other than insertion: more likely, it’s just not noticed immediately. Even strong uterine contractions — like with a very heavy period — won’t make it “go further” into your uterus, although they can increase the risk of it coming out. And that’s called…

2. Expulsion: 2–10% in the first year. Specifically, the Mirena has a rate of 2.3% if you got it only for pregnancy prevention and 10–13% if you got it for a medical reason, such asendometriosis. The evidence of nulliparity (no baby) increasing your risk of expulsion is dicey; stronger risk factors are being under 20, insertion during your period, or having heavy/painful ones. If you get another IUD, there is a 30% chance of having another expulsion: most recommend closer monitoring the second time around.

3. Infection: Having an IUD straight up doesn’t raise the risk of pelvic infections: what does raise the risk is pre-existing gonorrhea or chlamydia at insertion. This is why the rate of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in women with IUDs drops to the same as women without after 20 days of use. Even if you do have chlamydia or gonorrhea at the time of insertion, the absolute risk of PID is still so low that it’s considered reasonable to test you and insert the IUD before the results come back. A single episode of PID will cause tubal damage infertility in about 10% of cases. (The Mirena might actually prevent pelvic infections, a possibility that IUD expert Dr. David Grimes describes as “tantalizing.” I am not yet where you are, Dr. Grimes, but I hope to get there one day.)

4. Ectopic Pregnancy: “0–0.5 per 1,000 … compared with a rate of 3.25–5.25 per 1,000 among women who do not use contraception.” So your risk of ectopic pregnancy is lower! However, if a pregnancy does occur with the IUD in place, it’s proportionately much more likely to be ectopic.

5. Infertility: Tricks, not an IUD complication! Having a history of chlamydia, not IUD use, is correlated with infertility. Chlamydia does the crime, the IUD does the time AGAIN.

Similar to how side effects work, complication rates are highest at the beginning and then decline, but mind a parable? You’re too kind. You get Mirena and notice something like a mild yeast infection that never quite goes away. You go to your provider and they say: there’s very little chance that the IUD could be causing it. Somehow, after they say this, your discharge magically goes away forever!!!!!!

If you think your IUD is causing something to happen to your body that you don’t like, look into it with your provider. There’s a good chance that no matter what the cause, it can be managed. Then, success all around! You keep the birth control you wanted AND you’re happy on it. But you are the only person who can decide if a side effect is tolerable, how long is too long to have it, how many times you’ll try treating it or whether you’ll try treating it at all. If you want it pulled, that’s exactly what you should have.

& Goodbye

Can’t believe we covered it all. Guys, I feel amazing — and whoever brought the guitar, thank you! I love the way “Time of Your Life” sounds on an acoustic, especially when we’re all singing along.

Only one thing left: saying goodbye. IUD removal is usually very quick: we just grab on to the strings and (gently) pull. If you’re getting it taken out because you want to get pregnant, both IUDs have an immediate return to fertility after removal — 54% get pregnant within the first 3 months and 80% within a year, so congratulations may shortly be in order. I leave you with a personal photo of my top bro Alison’s enviable gyno gameface as she pulls out my ParaGard to replace it with half of a best friend necklace:

References

Big time: Contraceptive Technology 19th edition / Managing Contraception

ACOG Practice Bulletins: Long-Acting Reversible Contraception: Implants and Intrauterine Devices, Intrauterine Device and Adolescents

A great breakdown of actual PID risk

http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/9789241563888/en/index.html

http://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-problems-related-to-intrauterine-contraception#H2

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/575550

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21691183

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21872240

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21668037

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19442775

http://www.mirena-us.com/hcp/ordering_and_reimbursement/how_to_order.jsp

http://pds7.egloos.com/pds/200710/05/64/pid.pdf

http://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-intrauterine-contraception

Further Reading

http://maybetheiud.org

http://bedsider.org

http://www.reproductiveaccess.org/contraception/iud_aftercare.htm

Some more on funding: http://www.communityobgyn.com/uploads/files/misc_info_packet.pdf

ParaGard patient info: http://www.contracept.org/docs/paraguard-patients.pdf

Mirena patient info: http://berlex.bayerhealthcare.com/html/products/pi/Mirena_PI.pdf

If you want an insertion video, here’s one.

Lola Pellegrino is a registered nurse with a tumblr, and is well on her way to becoming Dr. Queer, Medicine Woman. Do you have a health question for her?