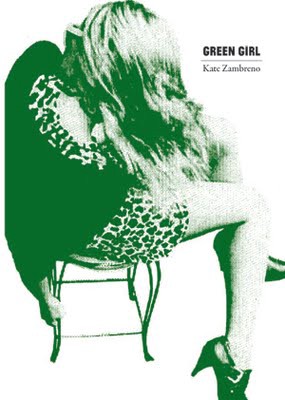

A Conversation With Kate Zambreno, Author of Green Girl

Edith Zimmerman: Kate! I reviewed your novel Green Girl for The Morning News’s annual Tournament of Books last Friday. The book wasn’t my cup of tea, but I felt weird saying so, because it so clearly was other people’s cup of tea. For instance, while I was writing the review, someone I didn’t know emailed me, sort of magically (almost spookily) out of the blue to say:

I just read Green Girl, by Kate Zambreno, and it has just blown my tiny little heart to shreds. I’m writing in the hope that one of you might like to do a feature on it, or interview the author. So then I could join in the conversation in the comments because I just have so many feelings and opinions about this book.

It’s the story of Ruth, a young American woman living and working in London, as a department store perfume-dispenser. It is so, so good, and fierce and nihilistic and about what it is to be a girl desperately seeking her identity and watching movies and having depressing sexual encounters and looking very stylish. In case you are wondering, I’m not a publicist, and I don’t know the author, I’m just a blogger (I wrote a review here if you are interested).

People then called my review “lazy” and said it was the “sorriest” part of the tournament so far. So, it was an exciting day! Ha. I can only imagine what’s it like seeing your book dissected online.

Kate Zambreno: Yeah, it’s pretty weird. I mean, I’ve received negative reviews in the past, and I liked to think I was someone that could handle a few bad reviews. But overall, prior to this Tournament most of the reviews of Green Girl have been really really positive. So I was totally unprepared for how passionate these Tournament of Books readers and fans were — I mean, they go for the throat. And almost overwhelmingly people who were commenting about this seemed to just really passionately hate the book. Initially I was really shocked by it, and felt really raw and sensitive about it. It was a lot to calibrate.

I was aware that often writers deemed “experimental” once they enter the mainstream are met with passionate readers who really, really hate works that veer from the traditional novel — in terms of plot or character, etc. But this was really my first entrance into any mainstream readership. I hoped it turned some new people onto the book. I think this novel really seriously challenged some people. Maybe that’s a good thing. But I was surprised sometimes at the level of vitriol that seemed really personal — towards my intellectual capabilities or talent as a writer, for instance, or towards the main character, that didn’t recognize that part of the frame of the novel is having a narrator who was commenting on and interrogating this character as well. I took it personally, but it also felt personal. But yes — I’ve had to think about how to get a thicker skin as a writer. I still need to figure it out. I think part of being a writer for me is having a thinner skin — to be receptive, aware, sensitive. But I need to stop fucking Googling myself. I had writer-friends when this all happened — bloggers and novelists with much bigger readerships/followings than me — tell me that I need to stop Googling myself, reading my reviews. I’m still trying to figure that out. I do wonder whether there’s more vitriol/hate/condescension leveled at women writers, especially women writers who feature young women as their main characters — a conflation with the author and the character, for instance.

EZ: I feel bad, because my review didn’t mention the narrator. And one of the earliest comments on TMN called me out on it, and I was like, shit. Because it was totally fair. I wrote a comment at the time, but deleted it right before posting, because I didn’t know if it was stupid/embarrassing to be like “you’re right, I messed up.” But, they were right, and I messed up. And I didn’t mention the narrator mostly because I didn’t know what to make of her. I thought of her as a sort of mysterious, nebulously motherly figure (Ruth’s creator?), although I didn’t feel confident enough to say so. Afraid I’d missed something.

A lot of the pro-Green Girl commentary has mentioned that it’s good and important to challenge a reader. And that I’m wrong for essentially saying “I didn’t like this book because I didn’t like the girl in it, lol.” Which also is fair, and makes me want to be like “but you guys I’m not a book reviewer, I don’t know anything, they just sent me these in the mail, ahhhh,” but that’s also a stupid cop-out.

(And I feel a little ridiculous even putting myself into this conversation, because you wrote a novel, and I wrote a review. That a lot of people thought sucked. I would love someday to make a book, and I think it’s awesome that you have. (Multiple books!) Also, people should obviously buy Green Girl and read it. [Or buy it from Indiebound!])

So, my question is: do you like Ruth? Or: how do you feel about Ruth? I kind of wish Ruth could be with us on this email thread, although it’s hard to imagine her on the computer. (Would she have a Facebook profile?)

(And I know what you mean about reviewers conflating young women writers with their characters — sort of like people see the book and see the author photo, and it’s like they hear this implicit whisper: “here’s my book, here’s me, please be gentle, I can only think about myself!”)

KZ: The novel exists for me in tension between this character, Ruth, and this ambivalent, ambiguous mother-narrator (so yes! as you said!). I started this novel in my mid-twenties when I was working retail in London, at Foyles Bookshop, and devouring for the first time all of the silver Penguin paperbacks of Jean Rhys and the golden Peter Owen paperbacks of Anna Kavan, and Jane Bowles. And at first the work existed on one level — channeling up the ghosts of the past, but then I began to realize that the modernist novel of the stream-of-consciousness of an alienated girl or woman in the city had really been done (see: Mrs. Dalloway, see: Two Serious Ladies, see: Good Morning, Midnight, see: Asylum Piece), and so wonderfully and agonizingly at that. So the narrator-character developed as I began to think about the idea of the girl as character, all the girls who have been trapped in some sort of beautiful protected amber as tortured or flitting muses and projections in all of these novels by the male “genius” gods (Virgin Suicides, cough). A work that Green Girl is in dialog with is the Portuguese writer Clarice Lispector’s slim, devastating The Hour of the Star — about a girl living in the slums of Rio and working this blank yet somehow mystic experience as an unloved, orphaned typist enthralled to Coca-Cola and Marilyn Monroe — although the god-narrator in that book is male, and I had always wondered why. I think of Green Girl as a meditation on youth and beauty, but also an interrogation into the creative process, into writing, into being a woman writer, into the girl who lives her life as an object, a character, into the blank yet mysterious girl in literature and film by male auteurs. The Hour of the Star is about class, rigorously, as well as gender — about the invisibles of society — but in some way I feel Green Girl is too, Ruth is a nameless foreigner, a shopgirl.

I think I used the narrator oftentimes to indicate my ambivalence towards Ruth, my cruelty towards this girl, who is in many ways self-consciously a character, a cipher, a grotesque. I often experienced horror at Ruth. I didn’t always like her. I wanted her and Agnes to be banal and boring sometimes. I love Ruth though. I love her, I loathe her. I think I am asking whether this loathing comes somewhat out of our culture. I was interested in the role of the blonde ingénue as a Hollywood construct (when writing the book I was really aware of all these Saw-like horror films, or like Catherine Deneuve in Roman Polanski’s Repulsion), the blonde as this victim character. I was also kind of obsessed with celebutantes like Britney Spears and Lindsay Lohan, and their quite public unraveling and the way the media functioned as a cruel coliseum. So for me there was a whole other fascinating layer to the Tournament of Books spectacle — the passionate vitriol directed at Ruth — that is basically doubling what I was investigating and even echoing the book’s own narrator. Yet, I don’t think Ruth is entirely a wet-blanket — I see glimmers of possibility in Ruth, the sort of coming to consciousness. A watchfulness, an intensity.

Totally right and interesting what you say about Facebook — this is totally a pre-Facebook text — identity and the creation of identity in public is so different now. She’d totally have a Tumblr. My critical memoir Heroines that’s coming out through Semiotext(e) in the fall deals a lot with how women writers have been read historically, beginning with modernism, but also with girls writing, what has prohibited the girl from writing. The work tries to investigate this idea of the girl as the eternal character, beginning really with Zelda Fitzgerald, how this has affected ideas of subjectivity, but also how girls and women are authors now on their blogs and Tumblrs, etc.

I was really struck by the insistence in this particular forum that Green Girl was only a novel for a certain young girl. I thought this was totally bogus. I mean, yes, I feel really gratified when people say that they identified with Ruth — if literature can make you feel less invisible, less marginalized, more known, that can be a magical thing. But literature should be more than about identification. It totally brought me back to Virginia Woolf in Room of One’s Own — the idea that “feminine” experience as written in a novel will be derided as not “universal,” not potentially all the stuff for literature.

And a lot of people were pathologizing Ruth — I do not see the work as a study of depression, but certainly not an anthropological portrait of mental illness. In Heroines I write: “ANXIETY. When he experiences it, it’s existential. When she does, it’s pathological.” A character does not have to be redeeming, or likable. I think of Ruth as an antiheroine. And I find too few examples of the antiheroine in women’s literature, and certainly too few that are celebrated as literature. Or as the blogger Meg Clark put it, the “hot mess.” With Madame Bovary people weren’t like: “Oh my god Gustave your heroine is a drip.” But with Edna Pontellier in Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, a novel modeled on Flaubert’s work, critics were scathing, saying they didn’t care for her character’s “torment” and she was also basically ostracized afterwards. Why this difference?

EZ: But Chopin got the last laugh (maybe? actually this is territory I’m not so familiar with), because high schools and colleges teach that book now as a classic. (I think I wrote about The Awakening for the essay section of an AP test. Although admittedly I don’t remember … anything about it. So that’s maybe irrelevant.)

Green Girl has also gotten a lot of wonderful praise — the Bookforum and Vanity Fair reviews in particular, plus you’ve got all five-star reviews on your Amazon page.

Another thought, and this is sort of moving sideways, but it’s something I think Green Girl does a great job of illustrating — how female beauty (also beauty in general) affects its possessor. A beautiful girl like Ruth produces a strong response in others (i.e. makes them want to be near her), but ultimately it’s not part of her personality or something she earned, so she has this massive power that it isn’t actually “hers,” if that makes sense. (I mean, it is, but it’s not something she created.) (And then who *is* she, and would anyone want to be near her if they knew that person? And if her inner self were unpleasant, maybe just keep it hidden beneath beauty?) So it’s almost like this cloth over the birdcage, and she’s like “I think there’s a bird in here, wanna see?” but everyone else is just like “stop chirping, you’re rustling the cloth, we like the cloth.” Or, being beautiful as a gift and a curse that gives unusually much when people are at their most beautiful and takes the most when people feel that beauty fading, because it seems easy to mistake it for personality. (See: all the plastic surgery slippery slopes.) Or, maybe I’m rambling/not making sense. But I do really admire how you addressed that. The separation between the inside and the outside. Figuring out where they meet.

Also Ruth would totally have a Tumblr. Excellent call. (GreenGirl.tumblr.com appears to be taken, though. Not that she’d name her Tumblr after the book.)

I hope people buy the book, read it, and discuss it — I’m really curious to know more people’s thoughts. Also I’m looking forward to your April 25 reading in New York!

Is there anything else you’d want to talk about here? I both want to go on and on, but also not get too carried away. Pique interest without overstimulating. But what do you think?

(Oh, also The Hour of the Star sounds so good!)

KZ: Yes — it’s amazing! You should totally read it. There’s a new translation too, by biographer Benjamin Moser, in a hot new candy-colored edition. And I like what you write here — I think more than Ruth being beautiful, it’s about her being concerned and aware of being the perfect image on the outside — the archetypal blonde, the young pretty girl — being so aware of how others looked at her, and this alienation, this gap, between her interior and her surface. Yes “figuring out where they meet.” I like that. I think that’s a lot of what the book’s about, for me.

I’m glad we had this discussion. I felt, when I read your piece, that you’re someone whose wit and community-building I had always admired, so I felt that we could have a good conversation about the book. Books are meant to be discussed, debated. I’m glad we did. And about the praise — it’s gotten some pretty gratifying praise, definitely, which is maybe why it was chosen. Although, I think what was interesting about the Tournament of Books hullabaloo is that I was obviously really an outsider, both in terms of why I write, and what my obsessions are as a writer, and in terms of status. I mean, I’ve never been reviewed in The New York Times Book Review, Ye Olde Gray Lady, I’m pretty sure I’m not on their radar, I don’t have an agent, or a publicist, or a billboard, I’m not published by a major press, or even a major indie. I don’t make money as a writer. I have four Amazon reviews, yes, so far (I’m imagining if any of these Tournament people go to my Amazon page they won’t be all five-stars anymore) but I’m pretty sure Jeffrey Eugenides has like five million or something. I don’t know. That’s obviously hyperbolic. I guess to me Eugenides, who in many ways I admire, is like the writer’s equivalent of — Coldplay. And me? Maybe I’m more Riot Grrrl, or something. (I love St. Vincent, but pretty sure I’m not the St. Vincent equivalent of writer. I’d love to read that writer, though.)

But what kind of unnerved me, initially, was some of the commentariat’s assumption that … I’m not as passionate or involved or full-time in being a writer. That I’m not a capital-W writer whatever that is. The line kept on circulating in my head: Mr. Fitzgerald is a novelist, Mrs. Fitzgerald is a novelty. But even though I really don’t get paid to write, it is my full-time, intense, all-encompassing thing. And I have fun doing it. Most of the time! Sometimes a panicky, hair-pulling, agonized fun … I guess that doesn’t sound like fun. But anyway. I had fun doing this, Edith. Thank you! And if any of The Hairpin readers have questions for me, about Green Girl specifically or just writing, I’d be happy to answer.

Green Girl is available now; Kate Zambreno will also be reading in Durham, Atlanta, Baton Rouge, New Orleans, and New York in the coming months.