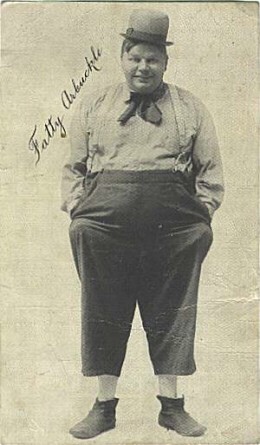

Scandals of Classic Hollywood: The Destruction of Fatty Arbuckle

by Anne Helen Petersen

Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle wasn’t Hollywood-hot. He didn’t have any high-profile romances, and the gossip mags never complimented him on his dashing evening wear. But he was one of the best physical comedians of all time, and from 1914 to 1920, he effectively ruled the movie business. He was Will Ferrell meets Chris Farley with a twist of Fire-Marshall-Bill-era Jim Carrey, and he was, and remains, a marvel to behold. Here was a man who, despite his mass, seemed to float across the screen, and whose comedy had deftness and grace — qualities Ferrell’s tighty-whitey romps, for all of their glory, distinctly lack.

But “Fatty” was just Arbuckle’s picture personality, the name given to his various characters in their endlessly hilarious approaches to “hayseed visits big city; hjinks ensue.” Off-screen, he refused to answer to the name, making explicit the distinction between textual and extra-textual persona that studio publicity worked so hard to obviate. Yet it was this off-screen persona that would eventually lead to his demise, when an alcohol-soaked weekend led to the most dramatic fall from grace in Hollywood history. I am not being overdramatic. This guy was ruined. On the surface, Arbuckle’s actions were the scandal. But as the details surrounding the event and its handling have come to light, it’s become clear that the true scandal was the willingness with which the studio heads threw their most prominent star under the figurative bus.

According to lore, Arbuckle weighed 13 pounds at birth, prompting his very slim father to question the child’s parentage. Totally pissed and skeptical, he named his son after his least favorite politician, Republican Roscoe Conkling. And so began a dramatic career centered on Arbuckle’s heft, which constituted the very core of his star text. Arbuckle’s mother suffered from various illnesses and difficulties following his birth (he was one of nine children), and his father, still convinced of his son’s illegitimate status, beat him regularly. Arbuckle’s mother passed away when he was 12, and Arbuckle, by then more than 180 pounds, was on his own.

Here the gauzy lens applied to every Hollywood discovery story goes into high gear: Arbuckle had a beautiful singing voice, and his friends encouraged him to try out for the stage. The audition he chose — to become part of a vaudeville revue — purportedly employed an honest-to-god massive hook to pull people off stage when they bombed. Arbuckle sang; no one clapped; the hook came for him … and he responded by somersaulting into the orchestra pit. Whether truth or fiction, this piece of apocryphal lore was reproduced time and again to emphasize Arbuckle’s dexterity and ingenuity.

Arbuckle spent the next decade traveling the vaudeville circuit, romancing and marrying another vaudevillian, Minta Durfree, in 1908. A year later, he made his first onscreen appearance, and began appearing in various comedy one-reelers [one reel of film = 10–12 minutes] before becoming a regular in the Keystone Cops series. Arbuckle’s size and comedic skill distinguished him immediately, and his films, especially those with Mabel Normand, became a sensation. She was the Wilma to his Fred, the April from Parks and Rec to his Andy from Parks and Rec, the [INSERT CUTE FUNNY GIRL’S NAME HERE] to his Jason Segel.

Arbuckle continued to refine his comedic trademarks, using his near-balletic control of his body to make it seem even more out of control. Dude was a PIONEERING PIE-IN-THE-FACER. He began directing and producing, recruiting and mentoring both Charlie Chaplin and (my total favorite of the silent comedians) Buster Keaton.

Directing Keaton in ‘Coney Island’

Arbuckle was the complete comedy package: a Judd Apatow who could act. And audiences LOVED him. Anything he was in, they’d see, thus setting the standard that holds today: overweight men can be stars, but only if they’re also funny, and especially if they use their weight as a point of humor. Arbuckle, however, was a stickler about the ways in which he’d use it. He’d fall over, do somersaults, land on his feet — anything to highlight his body’s liberty. But he refused any gag that framed it as a trap: he refused to flounder stuck in a chair, desk, or doorway.

Arbuckle’s popularity coincided with the rise of Hollywood and the concurrent rise in star power. To put a complicated period of film history in somewhat reductive terms, early films relied on actors, yet studios were reluctant to release the actual names of the stars themselves, in part because A Name → A Star → Power → The studio paying the star more for his/her perceived value.

But audience members weren’t stupid, and soon began giving their own names to various performers, i.e. “The Girl With Dimples,” or “The Girl With Curls” (though never “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo”). Through various means and for various reasons, actors’ names became well-known by 1912, marking the beginning of film stardom as we know it today. And with knowledge of stars’ names came the hunger to know about their off-screen lives: how they had come to Hollywood, what were their (nearly always tragic) life stories, how did they spend their new-found wealth (generally quite loudly), and how were they living their seemingly glamorous lives???

As a result of this newfound prominence, stars realized they could demand more from their studios — hundreds of thousands more, plus portions of the profits. Arbuckle was able to negotiate a contract with Paramount in 1914 that allotted $1,000 a day plus 25% of all profits and full artistic control. That’s like the deal between FX and Louis CK, only with a Will Smith salary. Even on that then-unheard of salary, Arbuckle was making millions for his studio, and by 1918, they agreed to pay him a million dollars a year for the next three years. Covert that to 2012 dollars and THAT IS SOME SCROOGE MCDUCK MONEY, YOU GUYS.

All over America, various Blue Bloods and Old Monies and East Eggers were already all sorts of anxious about the ”new” Hollywood wealth. Here was an entire “colony,” as it was then called, of lower class, un-educated, first- and second-generation immigrants suddenly flush with cash, just waiting to become Exhibit #1 in Why Poor People Shouldn’t Be Allowed to Have Nice Things.

Fatty Arbuckle was the first to very publicly evidence that maxim, and he would pay for his sins with his career. On September 5, 1921, Arbuckle and two friends drove from Hollywood to San Francisco, where they rented three rooms at the swanky St. Francis Hotel. They invited girls, got some under-the-table booze (remember: Prohibition), and started a good old-fashioned hotel-room-wrecking party. At some point during the night, Arbuckle was alone in one of the bedrooms with a young model-turned-quasi-starlet, Virginia Rappe. Rappe had first garnered notice after appearing on the cover of some famous sheet music, and parlayed her good looks into a stint as a Sennett Bathing Beauty. In other words, she was the 1920s version of the reality star, with the corresponding amount of cultural cache.

The details of what occurred next are muddled by years of scandal-mongering and sensational retelling, but here’s what’s clear:

1) Rappe attended the party and was alone in a room with Arbuckle.

2) At some point during the evening, Rappe became ill and was taken to the hospital.

3) After several days in the hospital, Rappe died of peritonitis, apparently from a ruptured bladder.

The press went public with Arbuckle’s involvement the day after Rappe’s death, proclaiming “S.F. Booze Party Kills Young Actress,” and alleging that Rappe had made a “deathbed plea” to “Get Roscoe.” Despite a dearth of evidence, rumors quickly began to circulate concerning Arbuckle’s role in Rappe’s death: he had crushed her under his weight; alternately, he had attempted to have sex with her and, finding himself impotent, raped her with a broken Coke bottle, thus rupturing her bladder.

Again, there was no hard evidence that either of these scenarios had taken place, but because both fit with understandings of Arbuckle’s image, based as it was on his weight and its resultant romantic complications, the rumors seemed to carry an aura of truth. For in years leading up to the scandal, Arbuckle’s image had amassed a complex asexual tension. The fan magazines labored to establish him as an unlikely ladies’ man — indeed, an unfortunately timed Photoplay feature, already on newsstands when the scandal broke, proclaimed, under Arbuckle’s byline, that “I am convinced that the fat man as a lover is going to be the best seller on the market for the next few years. He is coming into his kingdom at last. He may never ring as high prices or display as fancy goods as these he-vamps and caveman and Don Juans, but as a good, reliable, all the year around line of goods, he’s going to have it on them all.”

But Arbuckle had also spent the last six years on film diligently confusing gender identity.

As Sam Stoloff emphasizes in his ridiculously good essay on the Arbuckle scandal (and its relation to the Black Sox scandal — no seriously, it’s amazing; go find it, it’s right here. $2.17 Used! Snatch that UP!), Arbuckle’s comedy often pivoted on his asexual identity. Part of it was his natural babyface, and part of it was the fact that he periodically played babies (kinda like when Jim Carrey becomes a baby in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, only with more cheek mass). In other films, romance was played as a joke or, alternately, he cross-dressed to play “Miss Fatty.” Recall, too, that this was the early 1920s, when women were banding their breasts and bobbing their hair and asserting their subjectivity through crazy stuff like MOTHERFUCKING VOTING … you can imagine how a non-masculine, non-romantic, asexual dude might trouble the water, or, at the very least, make it easy for others to think him capable of sexual deviance.

Arbuckle was charged with manslaughter and endured not one, not two, but three trials for his alleged crime. I’m not going to go into the nitty-gritty of what went on in each trial, but try to imagine the mismanagement and publicity akin to the O.J. Simpson trial, and you’ll be getting close.

There may not have been round-the-clock Court TV coverage, but there was a thriving tabloid press and no shortage of bombastic rhetoric. The assistant prosecutor for one of the trials, Milton U’Ren, became known for his florid, damning description of Arbuckle’s lifestyle. To wit: “A Babylonian feast was in progress there. The defendant had sumptuous quarters with his friends … Food was spread, wine and liquor were served, and this modern Belshazzar sat upon his throne, surrounded by his lords and their ladies; there was music, feasting, singing and dancing.”

A modern Belshazzar! The last king of Babylonia, sundered amidst his decadence! That is some Game of Thrones-esque doomsday stuff right there!

However overblown his rhetoric may have been, U’Ren’s prophesies would ultimately prove correct. There was a hung jury, a retrial, and a final, resounding, acquittal. It became clear that Rappe had pre-existing medical conditions, often complained of stomach pains, and may have had a botched abortion or treatment in the days preceding her encounter with Arbuckle. (The release of this information smacks of slut-shaming and/or victim-blaming, but a pre-existing condition seems to be a much more logical cause of death than “sex with overweight person.” I mean, if we’re going to talk about wrongdoing, maybe we should focus more on the lack of legal birth control that may or may not have led Rappe to a backdoor abortion.)

Arbuckle was acquitted of all wrong-doing in the eyes of the law. But the court of public opinion had made its decision before the first trial even began: Arbuckle was guilty. Perhaps of violating a young woman, but definitely of being too much — too big, too rich, too tasteless. He became the symbol for Hollywood excess — physical, monetary — writ large.

The studio heads got the message: Belshazzar must be destroyed! Because if he wasn’t, the United States government, then on a bit of a regulatory kick, might take control of the film industry itself, handling censorship and determining what could and could not make it on the screen, or even how stars could and could not act off-screen. Plus, any sort of government participation could also mean that the government would take a closer look at how the studios were doing business, which is to say how they were making millions through monopolistic practices.

The studios also had to calm the ire of individual censors. Up to this point, every major city/area had its own censor or censorship board — someone who would watch a film and decide what was or was not improper for the city’s audience to see. Some censors were strict, others less so, and as a result, a single film could have fifty different versions, one for each city that deemed various parts immoral or unacceptable. (In today’s terms, think of how different a cut of True Blood would be for viewers in, say, small-town Iowa than for those in Manhattan.)

Point is: censors, like the rest of America, were increasingly convinced that stars’ immoral actions off the screen meant that they shouldn’t appear on the screen. In other words, young, impressionable youths shouldn’t see any film starring someone known to have committed immoral acts off the screen. The studios thus attempted to wine-and-dine the censors, inviting them to elaborate soirees where they could mingle with the stars and learn, firsthand, that they weren’t immoral assholes.

One such mingle occurred in August 1921, just one month before the Arbuckle scandal broke. Universal had a big, expensive film, Foolish Wives, that it was ready to release, but knew that the censors might chop it to pieces. Studio execs invited 14 of the most influential censors to a lavish party at Hollywood’s Sunset Inn attended by dozens of stars — including Arbuckle, who, according to one report, “was host at a big table and did his damnedest to hand the censors plenty of laughs.” Fast forward one month later, and you have Arbuckle in custody, the censors feeling duped, and any hopes of a free pass for Foolish Wives out the door.

Fearing threats of even more extreme censorship, the studio heads got together, all behind-the-doors/room-filled-with-smoke style, and decided to regulate themselves before the government forced regulation upon them. They formed the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) alliance, appointed the former Postmaster General, Will Hays, and told him to get down to business. (The postmaster general may seem like an odd choice for a censor, but at this point, the P.G. was the guy in charge of rooting out pornography, which was often sent through the mail.) Less than a week after Arbuckle’s acquittal, Hays banned Arbuckle from appearing in films and yanked his body of work from distribution. Although Hays eventually rescinded the ban, Arbuckle, once the most powerful star in Hollywood, was effectively blacklisted.

The studios were ready to regulate their own. Over the next two years, Hays and the MPPDA helped spin scandal (most famously: Wallace Reid’s heroin overdose), and each of the major studios inserted “morality clauses” into their star contracts. While stars did not necessarily adhere to these clauses, their existence served an enormous P.R. function, underlining the studios’ refusal to tolerate “immoral” behavior.

The fall of Fatty Arbuckle might seem like a simple tale. A man was in the wrong place at the wrong time, and paid the tragic price. But as should be clear, Arbuckle’s demise, like many star scandals, had much more to do with American anxieties about class and gender than any actual wrongdoing. Arbuckle became the figurehead for all that was dangerous about Hollywood — the unbridled wealth, the unchecked vice — and no jury could acquit him of being an overweight, asexualized man.

He was an easy fall-guy, but unlike his deftly acrobatic screen persona, he could not find his way back up. Arbuckle exhausted his fortune funding his defense, and lived afterward in relative poverty, finding sporadic directing work under a pseudonym. In 1932, with more than a decade between him and the scandal, he appeared in a series of two-reel comedies to great success and signed a contract with Warner Bros. to star in a feature film. That night, Arbuckle, all of 48 years old, died in his sleep.

Thirty years later, Arbuckle’s scandal, like so many from classic Hollywood, was given new life via Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon, which bypassed the story of Arbuckle’s acquittal in favor of a retelling that reads like an NC-17 version of Hard Copy. It’s so bad, and so truly libelous, that I dare not even copy it here, lest someone reproduce it out of context. But then, as today, readers wanted to believe the worst and the most salacious of their stars, in part out of schadenfreude, in part because it simply makes better reading. The more titillating, damning, and disgusting, the better. It’s not that different from looking for gore and grist in a movie plot — only with these tales, the characters end up unable to leave their homes, lose their livelihoods, and watch as their names become synonymous with immorality.

We don’t call ours stars “Fatty” anymore, and studios don’t (officially) ban stars from Hollywood. But we do let stars take on our personal anxieties, and shun them when they fail to embody them in ways that please us. We blind ourselves to corporate machinations that allow individuals to take the fall, and we make it easy to associate outsized bodies with the grotesque. Libel laws are more stringent these days, and stars are, in general, more circumspect. But I’m still terrified by what humans are eager to believe of one another, especially when class, gender, and body size intersect.

Previously: The Unspoken Tragedy of Natalie Wood.

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.